Stories of Paper explores the rich artistic legacy of this fragile material that not only became indispensable for record keeping and trade but has also proved essential to cultural interaction and intellectual exchange for two millennia. The exhibition showcases about 100 artworks from 16 museums and cultural institutions to explore the history of paper and the the vast range of artistic expressions of paper, with the aim of cultivating the visitors’ deeper knowledge of a familiar, yet ever more distant material. From the first century to the present, and from ancient Asia to Europe and contemporary Arabia, the artworks include books, manuscripts, prints, drawings and contemporary installations made of paper by Hassan Sharif, Abdullah Al Saadi and Mohammed Kazem, pioneers of Emirati conceptual art.

The History of Paper

The history of paper transcends geography and this exhibition traces its journey from East to West whilst transforming cultures and societies in the process, producing stories of cultural interaction and intellectual exchange on its way. This journey is told in 12 sections, all of which highlight the key qualities and varied use of paper across continents, including Plant-based origin, A Humble Material, Colour, Movement, Relationship with Light, An Untruthful Material, Memory, Fragility and Resilience, Space, Possibility of a Collection, A Medium for Reproducing Artworks and A Malleable Medium. Also included in the exhibition are the tools and techniques used to create paper alongside the varying materials that are classified as ‘paper’.

It is believed that paper was invented in China around 200 BC and then rapidly made its way to Korea and Japan and eventually travelled along the Silk Road. Traditionally it was created by using pressed plant fibres to create rudimentary sheets. In the Han dynasty, Cai Lun, the 2nd-century court official refined and documented the papermaking process. However, papermaking seems to be have been invented at least 300 years previously with its roots, quite literally, in ancient Egypt with the papyrus plant.

Song-Dynasty China

During the Song dynasty (960-1279) the government produced the world’s first known paper-printed money, which research has shown was circulated not only in China, but in neighbouring countries such as Myanmar, Thailand and Vietnam. Court Officials and scholars were regularly using paper for communication and as part of Confucian culture to produce letters, calligraphy, and painting. Alongside secular use, it was also crucial to spread the word of Buddhism in written prayers and sutras. From China, paper naturally moved to nearby countries through the demand for Buddhist texts and trade.

The Islamic world absorbed this material into their culture and its use then spread across the Middle East to the coastal trading routes used by merchants to the Mediterranean and into Europe. By the 11th century, the first paper mills were documented in Al-Andalus (Moorish Spain, 8th to mid 15th century). Shortly after, in the 13th and 14th centuries, the advancement of mass paper production took place in Italy and France and the demand for paper grew exponentially worldwide. This exhibition seeks to explain why paper, a common yet precious good, was quickly adopted and sought after by cultures from every part of the world.

The History of Paper in Korea

Buddhism was an early conduit for the demand for paper and continues the thread of the history of paper. In Korea, the precise origins of printing technology is still difficult to establish, but Buddhism is considered as one of the main reasons for the development of printed material in the country, as it was a useful tool in the transmission and dissemination of Buddhist teachings and prayers. By the 5th century, the religion was already flourishing on the Korean peninsula and, during the Unified Silla period (668-935), woodblock-printing technology was being used for mass production of the Buddhist canons.

The art of papermaking was believed to have been introduced into the country from Japan by a Korean Buddhist monk with papermaking skills and became well established by the late 6th century. Buddhism may have led the way for paper to be introduced in Korea, but Daoist and Confucian texts were also popular among the country’s aristocracy. The oldest surviving woodblock print in the world is considered to be the Pure Light Dharani-sutra, a small Buddhist scroll discovered in 1966 at the Pulguk-sa Temple in Kyongju. Research has shown that was probably published during the Silla dynasty, around 751. There is an example of this type of printed sutra, from the 14th century – attributed to Hui Nen (638-713), in the exhibition.

The actual paper in Korea, as in China, was originally made out of a variety of plants: hemp, rattan, mulberry, bamboo, straw, seaweed or mulberry. The best Korean paper was hanji, made from the inner bark of paper mulberry trees and called dak ji (Broussonetia papyrifera) and is still widely used today. By the early 15th century, an Office of Papermaking was established in the capital employing almost 200 papermakers, mould-makers, carpenters and civil servants. Paper soon became an indispensable material in everyday life, handmade Korean paper was used by scholars for calligraphy, books, boxes, etc. In the home it was used for doors, walls, and windows, as well as for furniture and screens. Koreans seem to be the only people to also have used paper for floors.

Papermaking in Japan

In Japan, the history of paper is also tied to Buddhism – it is thought that it was Korean Buddhist monks that first introduced the craft of papermaking around the early 7th century. As in Korea, papermaking developed at a rapid rate in the country, and became the conduit for literati and religious texts. It also enabled a native script to develop away from Chinese characters. In Japan, form, quality, and beauty became essential characteristics of making paper and the craft was elevated to a much admired and appreciated skill.

Washi (paper) has been made throughout Japan for centuries and is typically made using the nagashi-zuki method, in which a viscous substance made from plants is added into the pulp mixture, and the screen is rocked back and forth and from side to side so that the mixture flows over the screen. This allows the paper to be made with longer fibres, which become tightly interwoven, resulting in a stronger product.

This strong, thin paper is used not only for books, drawings, and paintings, but also as a material for architecture and everyday items including sliding paper screens (shoji) and partitions (fusuma), and many other domestic uses. When machine-made paper from the West began to be imported into Japan in the Meiji period (1868–1912), people referred to Japanese paper as washi in order to distinguish it from Western paper. The traditional Japanese paper used in printing ukiyo-e (woodblock prints) was handmade from kozo (mulberry, Broussonetia papyrifera), which was absorbent, flexible, and dimensionally stable even when moistened for printing. An example of this type of paper in the exhibition is used in Under the Great Wave by Hokusai.

The Art of Papermaking moves to Persia and Beyond

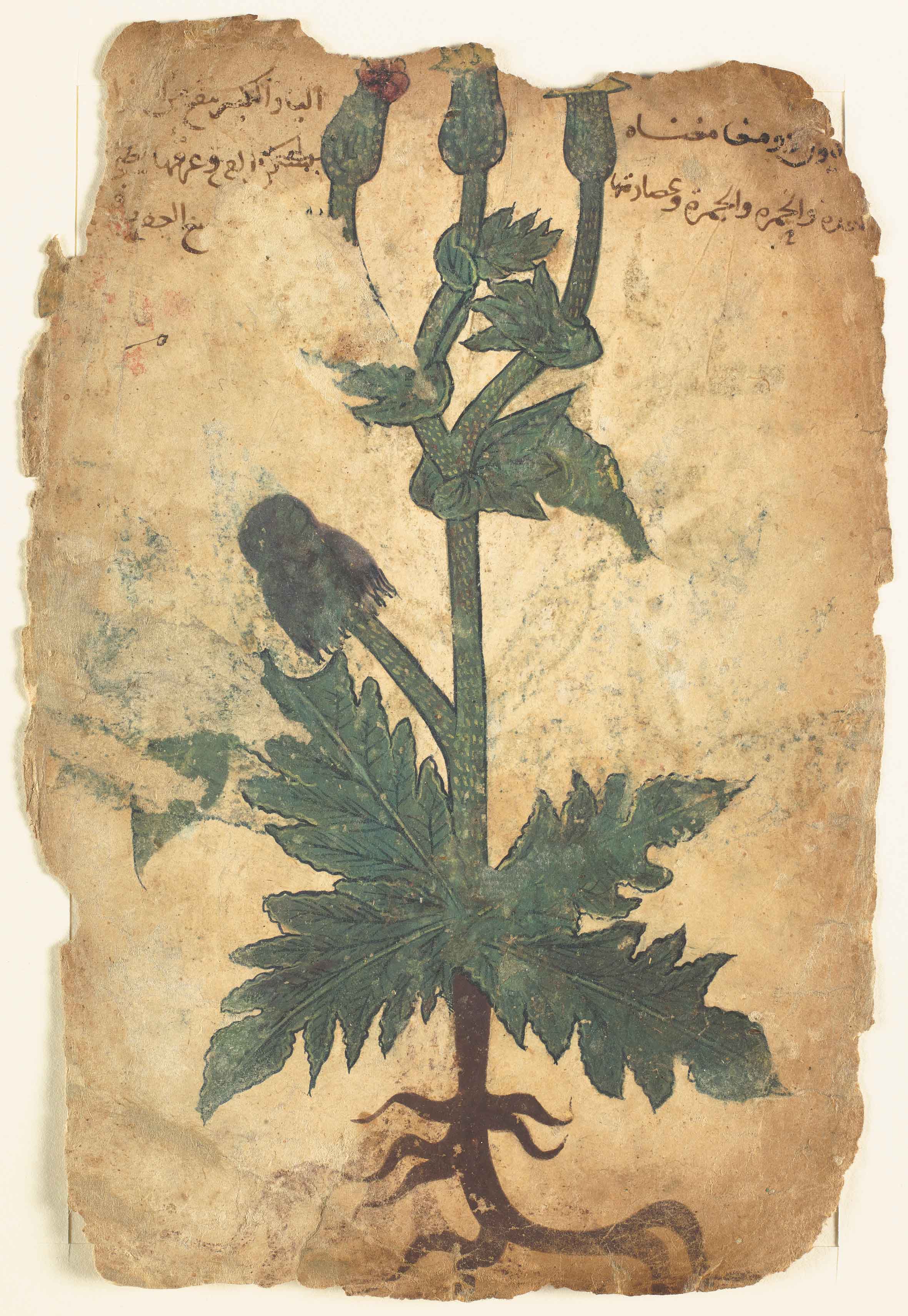

Papermaking was relatively confined to East Asia until around 7th century, although small amounts of paper were probably imported into central Asia and Sassanid Persia along the Silk Road in the 6th century. By the 8th century, papermaking seems to have been established in Samarkand, which became a centre for the craft. The Timurid Empire (1370-1507) was the last great dynasty to rise from the Central Asian steppe and its founder, Timur, brought craftsmen from a range of conquered lands to his capital in Samarkand to create an imposing city that merged Mongol might with Persian culture to become a centre of Islamic art.

In this strong culture, an abundance of paper allowed science and the arts to flourish. Other great centres of art and paper production could be found in Tabriz in present-day Iran and Baghdad in Iraq, as well as in Cairo and Damascus. During this time the arts of the book, including illuminated and illustrated manuscripts of religious and secular texts, flourished through court patronage.

Paper was first introduced into Europe via Al-Andalus and by the 13th century paper mills were set up in Northern Italy to service the trade, which expanded further into Europe in 14th century. Paper had finally completed its journey around the world – the Arabic word rizmah means a bale or a bundle, the Spanish made rizmah into resma, and the French said reyme, which finally developed into ream in English.

Discover the History of Paper in Paper Stories, until 24 July, 2022, Louvre Abu Dhabi, louvreabudhabi.ae