Incense is complex, it takes many forms and can contain a wide variety of plants and minerals, reflecting the cultures and tasks for which it was used. It was known to have been used in ancient India, mentioned in the Rigveda, circa 1500-1000 BC. In ancient China, according to archaeological reports studied by Susan N Erickson (Boshanlu: Mountain Censer of the Western Han Period, 1992), incense burners, of the hill censer type (boshanlu) have been found in tombs dating to the reign of Han Wudi (r 140-87 BC). This long history in China may date back even further to the pre-Qin period (before 221 BC), playing a prominent role in ancient Chinese religions and court activities, as well as in many aspects of daily life. Later, other forms of incense burners were introduced to East Asia, coinciding with the eastward advancement of Buddhism, as it was transported along the trading routes of Asia.

Incense came from many sources, and its makeup changed from country to country. Aromatic substances and their related products were highly prized in antiquity and they seem to have been widely used in connection with religions and other important ceremonies, first among royalty and the elite. It was also used in medicine, cosmetics, an perfumes, establishing an important position in international trade and exchange. In particular, frankincense and myrrh, both of which are aromatic resins obtained from trees in the Burseraceae family native to the regions of northeast Africa, the Arabian Peninsula, and India, were traded as goods along the Silk Roads. In ancient Chinese texts, frankincense (ruxiang) was recorded as originating in several foreign countries, such as Daqin (Rome), Dashi (Arabia), Persia (Iran), and Tianzhu (India) – with incense from Tianzhu being closely associated with Buddhism.

Along the Silk Roads

This network of incense routes was an important part of the Silk Roads, connecting ancient Arabia, Yemen, Somalia, Egypt, India, Europe, Southeast Asia, and China by land and sea. Yemen became a major hub for the trade of incense during the first millennium BC, with trade reaching a climax between the 1st century BC and the 2nd century, reaching as far as the Mediterranean world from Persia and South Asia. However, it was the advent of Buddhism from around the 1st century that played a critical part in China’s evolving incense culture and the role of fragrance in China. New liturgical and meditative practices were introduced to its temples and monasteries, where burning incense was a form of reverence for deities, purifying the temple space.

Buddhism attained new heights in Tang China (618-906), when the burning of increasingly complex aromas and smoke was needed to accompany certain rites. The great advances made by Tang shipbuilding and navigation enabled these aromatics, which had earlier arrived by land, to reach China by sea.

In 659, six critical perfumes were singled out by the Xinxiu Bencao (Newly Reorganised Pharmacopoeia): agarwood, frankincense, cloves, patchouli, elenni, and liquid amber. The poet Du Fu (712-770) described blended incense used in temples as a scented amalgam of a ‘hundred blend aromatics’ with odours of the ‘exhalations of flowers’. In the 8th and 9th centuries, there is mention of ‘perfume merchants’, who sailed the Nanhai (Southern Seas) of southeast Asia, searching for resins, sandalwood, agarwood, camphor and myrrh, among others. Enormous quantities of these perfumes were destined for the port of Canton (Guangzhou), which had become known as ‘one of the great incense markets of the world’.

Composition of Ancient Chinese Incense

The composition of Chinese incense has been explored in an interesting scientific paper published in 2022. According to Meng Reng et al, in Characterisation of the Incense Sacrificed to the Sarira of Sakyamuni from the Famen Royal Temple in the 9th Century, incense comprised local herbs such as lily magnolia and mugwort, which were mainly used by the Chinese in the Western Han dynasty (202 BC to AD 8). These plants were often mentioned in historical records such as Shi Jing (Book of Songs) and Chu Ci (Elegies of the South). With the expansion of the Silk Roads in the late 2nd century, other ingredients for making incense were gradually introduced into China through the northern Silk Road route from the west.

From the 2nd century onwards, the use of incense became more prevalent among the upper classes, involving court etiquette, indoor incense, and entertainment, as well as being used for purification, typically using the boshanlu type of incense burner. Exotic ingredients for incense also started to be imported into southern China through the maritime trade routes. Some scholars believe that frankincense may have appeared in China as early as the Western Han dynasty. The scientific paper also records the fact that an aromatic resin discovered in the Nanyue King’s mausoleum (the second king of Nanyue State ruling from 137 to 122 BC) had been identified as a close match to frankincense by the use of infrared spectroscopy. The four-hole connected censer unearthed in the Nanyue King’s mausoleum could burn four different incenses at the same time, resulting in a mix of fragrances. However, this type of multicavity censer was no longer used once the premixed hexiang products appeared during the Tang dynasty.

Complex Blends of Aromatics

Hexiang is a more complex blend of aromatic ingredients that has its origins in the earlier practices of burning herbs. With the increased importation of exotic incense from outside the country during the Tang dynasty, a variety of new products emerged such as these premixed fragrant powders, pellets, and ointments, changing the character of hexiang. A wide variety of aromatics were used, including agarwood, sandalwood, frankincense, and clove, all recorded in Buddhist sutras with descriptions of their usage.

The flourishing of Buddhism during the Tang dynasty also saw an increase in the number of temples being built. Famen, a much earlier temple, was revived and considered one of the most important temples in Chang’an (Xian), the royal capital of the Tang dynasty. In 1987, an extraordinary find was unearthed by a Chinese archaeological team at the temple. During the excavation in an elaborate underground palace, a Buddhist relic (sarira) was found – a finger bone of the Sakyamuni Buddha donated by Emperor Yizong (833-873). The worship of relics was an important part of Buddhism at the time, partly promoted by the arrival of new ideas.

The Chinese monk Xuanzang (602-664) had visited the great university of Nalanda, in India and brought back Sanskrit texts. This facilitated the spread of Buddhist sutras and teachings, as well as introducing relics to be worshipped, which, in turn, promoted the construction of stupas and pagodas to house the precious relics, making sarira worship increasingly popular, reaching a peak during the Tang dynasty. Therefore, Famen temple inevitably became a natural focus of Buddhist pilgrimage. As incense is so closely related to worship and Buddhist ritual, its use would have been common at Famen. Extremely large amounts of incense were consumed in Buddhist activities, as well as in the royal greeting ceremonies held by the Tang emperors – especially when honouring the finger bone sarira at Famen.

Three incense samples unearthed at Famen Royal Temple were analysed, and a yellow aromatic resin was discovered inside the seventh of the eight nested boxes, identified as elenni (sourced from several trees of the Burseraceae family found in the Philippines, Indonesia, Vietnam, and Guangdong province), providing the earliest evidence of elenni employed as an incense associated with Buddhist rituals. Other analyses discovered that pieces of fragrant wood placed in a silver container offered by the Tantric monk Zhihuilun in the late Tang period were agarwood, which also served an important role in sarira worship activities. The aromatic powder was a mixture of agarwood and frankincense, probably the main ingredients of hexiang at the time for use in specific Buddhist rituals relating to the royal family.

The Goryeo Kingdom, Korean Peninsula

By the Song dynasty (960-1279), incense had made the transition from the religious to the secular realm. It was a culturally rich and sophisticated age for China that saw great advancements in the visual arts, music, and literature. Scholar-officials had created a new moral order whose principles were founded on a revivified Confucianism. These circumstances made incense an indispensable part of Song literati life. The burning of fragrances became known as xiangdao, ‘the way of the scent’, and was believed to nourish the spirit as well as the mind. Blended incense was considered as an aid and companion to reading, contemplation, and meditation. The Song court’s influence was wide, including strong links with the Goryeo kingdom in Korea (935-1392), influencing their court culture.

With the spread of Buddhism to the east, incense was first introduced to the Korean peninsula during the Three Kingdoms period (57 BC-AD 668). The use of incense was initially linked to the arrival of Buddhism from China, but later it was used in Korea for various purposes such as state ceremonies, religious rituals, and even health reasons. Tomb murals from the Goguryeo era (the largest kingdom during the Three Kingdoms period), depict people using incense burners, and it is recorded that the Silla people (57 BC-AD 935) used to carry aromatic plant bags in their pockets regardless of their social hierarchy. A variety of plants used in Korean incense came through trade with China and maritime trade routes.

Incense in the Baekhe Kingdom

An important 6th/7th-century gilt-bronze incense burner from the Baekje kingdom has survived and is now a National Treasure of Korea. It was recovered from a temple site in Neungsan-ri, Buyeo, and would once have been placed on a Buddhist altar. Its shape depicting ascending levels of mountains, relates to earlier forms of the Chinese boshanlu, representing Boshan, a mythical peak where Taoist immortals dwell for eternity, topped by a phoenix standing on a jewel-shaped knob. Such incense burners had been widely produced in China since the Han dynasty; however, being produced in Baekje many years after the peak popularity of this type of incense burner, the Baekje incense burner shows many temporal and cultural changes in its composition. It is considerably larger than most previous boshanlu, and the rendering of the mountain landscape of the Taoist immortals is much more elaborate.

The overall composition is more dramatic, with many innovative and meticulous details having been added to the design. Designs that incorporate both Buddhist and Taoist elements can also be seen on a silver cup and saucer excavated from the Tomb of King Muryeong (r 501-523)and on a tile found in Waeri, Buyeo, indicating that both belief systems were an important part of the Baekje ideology and aesthetic tradition. The incense burner was not discovered at an ordinary Buddhist temple, but at the site of a temple affiliated with the Neungsan-ri burial ground – the royal cemetery of the Baekje kingdom. Whereas most incense burners at this time would have been used for Buddhist ceremonies, this piece was probably used in ancestral rites for a deceased Baekje king.

Their capital at Ungjin (475-538) was relatively short-lived, but it is considered an important period in Baekje history, evidenced by the numerous artefacts found in sites scattered throughout Gongju, a mountainous region in the mid-west of South Korea, halfway between Seoul and Gwangju. The Baekje Historic Areas represent the period from 475 to 660 during the Three Kingdoms period where excavations have helped how the introduction of Buddhism and exchange with China and Japan and how this distinctive culture developed a sophisticated style of architecture, culture, religion, and artistry, especially in metalwork.

Incense reached the height of its popularity during the Goryeo dynasty in Korea, when the court used incense as a prestige item that promoted their social status and authority, often using it exclusively for special state events and Buddhist rituals, placing incense burners on altars in prayer halls to offer incense to Buddha during prayer. As these burners were on an altar, they tended to have prayers engraved on the surface as part of their decoration. Goryeo-dynasty burners were generally divided into three types, a handled burner (byeonghyangno), which had a long handle attached to one side, suspended burners (hyeonhyangno) designed to be hung from the ceiling or placed on a stand; and placed burners (geohyangno) specifically made to be positioned at certain locations.

As in China, Korean incense comprised a wide variety of aromatic substances imported through trade with its neighbours. Buddhists during the Goryeo dynasty believed that incense connected them to Buddha and worshippers offered incense as this could also remove a supplicant’s afflictions and delusion. In general, there were four ways to use incense: by distribution (baehang); by exposing oneself to the smoke (hunhyang); daubing incense on the body (doyang); and burning incense (sohyang). Most of the surviving metal Goryeo-period censers take the shape of a deep bowl with an ornate lid having a fluted base sitting on three legs, showing the skill and expertise of the craftsmen As Buddhism had become an established influence on the Korean peninsula, Buddhist objects formed the core of Goryeo metalwork that has survived today. The Goryeo-period Buddhist incense burners inherited and built upon the Unified Silla tradition (676-935), introducing new and original forms, making these incense burners highly significant, as they form a bridge between the Unified Silla and the subsequent Joseon dynasty (1392-1910).

As incense in East Asia and its appreciation became more accessible, its use gradually spread to a wider audience and societies were formed to regularly enjoy incense-burning gatherings. Apart from plant-based ingredients, musk was also known and used at the time – most likely imported from the lands of the Tibetan Empire (618-842) that was connected to the trade of the Silk Roads via China at its northernmost point. There was also an active trade route that existed between Tibet and the Islamic world, linking the demand for aromatics, from the 8th century onwards. In Korea, musk was specifically used at the ceremony that took place in a formal hall of a building when receiving a royal edict. Juniper resin, camphor, sandalwood and eaglewood were also burnt at other formal or official gatherings. Later, after the fall of the Tang dynasty, ingredients for the incense for court rituals under the Unified Silla (668-935) were sent from the imperial court of Song China.

Incense culture decreased under the influence of Neo-Confucianism in the Joseon dynasty, but its popularity did not disappear completely as it had already become entrenched in daily life and ritual for many Koreans. The court retained expert artisans called hyangjang to specifically look after the aromatics used at court, whilst the general population would make incense for their personal or family use. For example, scholars burnt incense to concentrate on their studies. In order to conduct state ceremonies in accordance with the Confucian concept of ye (propriety), the king prescribed proper modes of conduct in five categories: auspicious ceremonies, mourning, military reviews, welcoming foreign envoys, and festive events. National mourning signified the loss of both a ruler and a parent figure and rituals acknowledging this were performed on a grand scale over a prolonged period according to royal protocols. Incense burning was considered an important part of these rituals, with ceremonies taking place at Jognyo, the Royal Ancestral Shrine in the capital, Seoul, they were also performed regularly at other royal tombs in the country.

Buddhism had arrived in Japan via Korea, bringing the art of incense to the country. In Japan, wood used in incense burning was first recorded at the very end of the 6th century, during the reign of Empress Suiko (r 593-628), when agarwood was first introduced (probably from China via Korea). With the introduction of Buddhism in the mid-6th century, along with Buddhist images and sutras, knowledge of incense and the utensils used in its preparation and use were also introduced. During the Nara period (710–794), Heijo-kyo, the capital, had strong connections with China, and the city was modelled on the Tang-dynasty capital of Chang’an.

The Japanese court and elite also modelled themselves on the Chinese court, including adopting the Chinese writing system, fashion, and adopting a Chinese-style of Buddhism and related culture. Therefore, incense played a prominent role in aristocratic life, initially remaining in the realms of the court until the end of the Nara period. During this time, courtiers familiar with the use of incense in Buddhist rituals in temple settings (sonae-ko) also began to burn incense privately in their homes (sorodaki-ko, or taki-mono), producing an aromatic product that differed from temple incense. The incense they used was kneaded and mixed into balls, and could contain up to 20 elements, which served not only to ‘perfume’ the air of the rooms and papers, but also as an indicator of refined taste, to perfume the body, clothes, and hair.

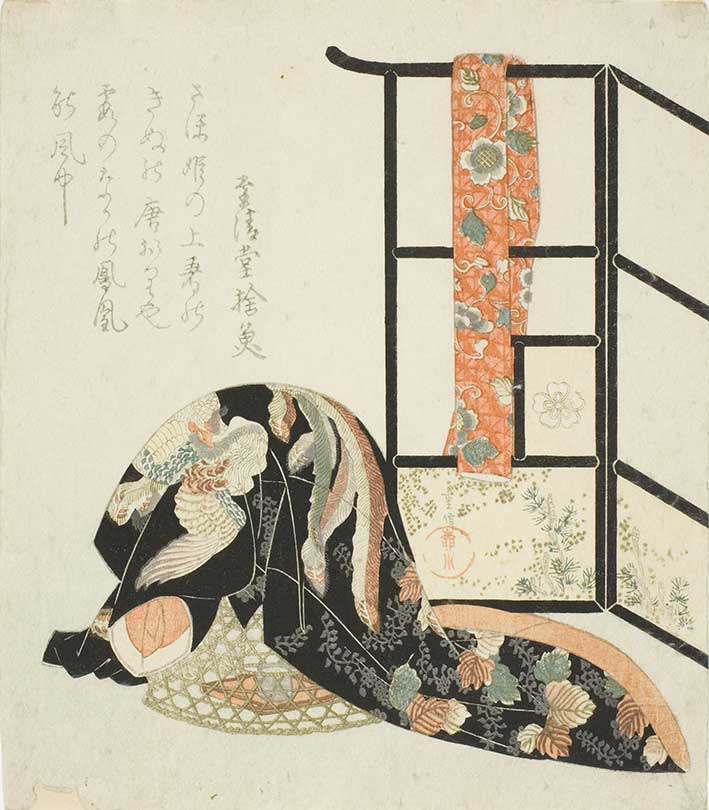

The popularity of incense culture in the later Heian period (794-1185) is recorded in the Japanese classic of court life, The Tale of Genji. It describes, in detail, the cult of incense and what was needed, including lacquerware utensils used in the preparation of incense. It also describes incense competitions that had a similar concept to poetry and painting contests. A typical incense set included an outer box containing smaller boxes for the storage of raw incense materials, such as agarwood, clove, sandalwood, musk, amber, and herbs, as well as small spatulas for preparing the mixtures. Other popular ingredients included aloe, frankincense, pine, lily, cinnamon, and patchouli. Aristocrats were expected to know how to mix aromatic imported woods with other plant products and compound them into burnable, fragrant incense, called koh. During the Kamakura shogunate (1185-1333), a new approach to Buddhism was introduced from China – Zen. This brought a new way of appreciating incense that was first developed among the samurai class. Agarwood (jinko) was particularly popular and incense woods were imported in large quantities.

The etiquette of incense appreciation further developed during the Muromachi period (1392-1573). In the 1400s, similar to the development of the ‘way of tea’, chado, ‘the way of incense’, kodo, developed in parallel to the tea ceremony. The burning of expensive, rare incense woods on special occasions increased their value, and made them a rare and appreciated experience. Incense-based games were extremely popular where participants took turns smelling, appreciating, and guessing the ingredients of a certain type of incense. In one variation of the game called Genji Incense (Genjiko), types of incense or combinations thereof hint at chapters of The Tale of Genji, which the participants had to name. In the perfume competition chapter of the book, the judge, Prince Hotaru, complains that it was so smoky that he found it very hard to judge the perfumes properly. The author, the court lady known as Murasaki Shikibu, describes one of the perfumes as ‘a calm, elegant scent,’ another as ‘full and nostalgic’, and one as ‘bright and up-to-date with a slightly pungent touch’ and another as having ‘a gentle aroma and rather touching tenderness.’

Incense games remained popular in the Edo period (1603-1868) among the samurai classes and court aristocracy. One game involved identifying 10 different types of incense, however, they did not use the earlier kneaded and mixed incense compositions, but the actual woods themselves, creating incense games to compare and name the woods. By the mid-Edo period, wealthy merchants could also appreciate incense, spreading the game culture to other classes.

For centuries, East Asia has deepened its association with incense, with Japan and Korea developing their own particular forms for cultural and religious events. The interest in incense remains strong today, being used in worship, privately at home, and given as gifts for celebratory occasions. Thanks to the initial trade and connections formed in early trade along the Silk Roads, incense remains as popular and recognisable as its ancient relatives – not only in India and East Asia, but around the world.

Buy tickets for Silk Roads at the British Museum, London, to 23 February, 2025. Objects from Nara, Chang’an, and Silla are on display in the exhibition with other objects from East Asia.