Asian Art Newspaper talks to the Japanese contemporary artist Izumi Kato

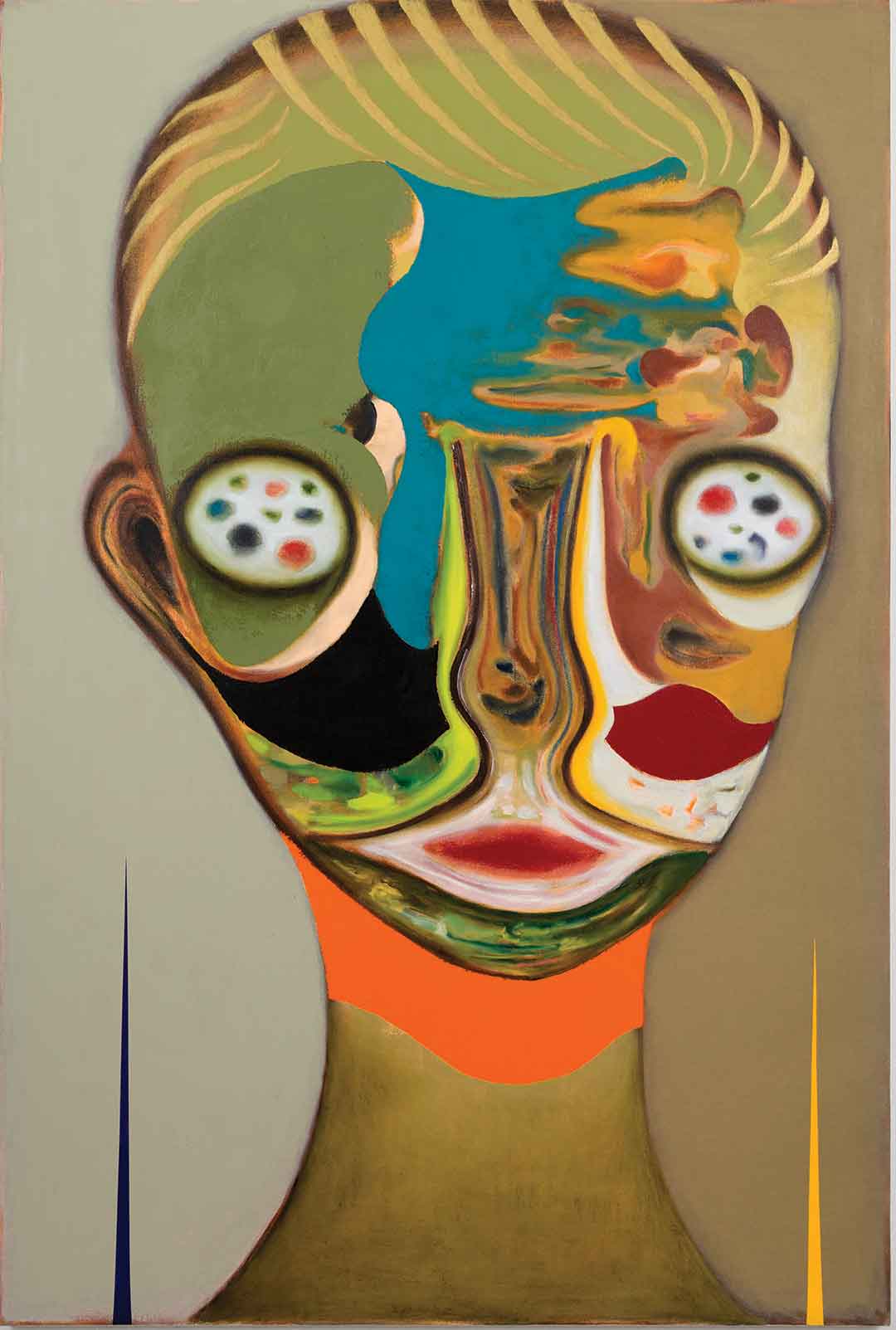

The Japanese artist Izumi Kato has a practice is captivating and singular, echoing his vision of what art should be. Depicting human-like forms, he sets the stage for the story to be told, a story that the viewer can imagine. Relying on his hands instead of the brush when painting, he brings together line, form, and colour, in order to create works that resonate with the viewer that reach an almost contemplative state. Beyond painting, the Japanese artist Izumi Kato (b 1969) also uses other materials such as stone and fabric, completing intriguing small sculptures, as well as large-scale installations. During the opening of his latest exhibition in Paris, Izumi Kato discusses his trajectory, sharing his thoughts on his approach and his artistic universe.

Asian Art Newspaper: You decided to become an artist when you were thirty years old. What prompted you to leave your previous life behind and reinvent yourself as an artist?

Izumi Kato: Originally, I studied art at university, but I was not a very interested student. I nevertheless graduated, and then started looking for a job in order to support myself. Working, however, meant entering active life, becoming a full member of society. It was a strange and trying time for me, as I was confused and disoriented by what I saw in society: for example, I was puzzled by the whole money-spending circuit and, in my opinion, there were many aspects of life that did not work properly.

Then, every time I faced a situation I could not understand or comprehend, I kept wondering if as an artist, I would have more choices and alternatives, allowing me to react as I felt best. I came to the conclusion that perhaps the art world was different, and would be more welcoming to me. I realised how concerned I had been, and decided it would be best to make a fresh start, devoting my entire time to painting. With the world organised as it is, I came to understand that the only way I wanted to live was as an artist. I reached that conclusion around the age of thirty.

AAN: Your practice is quite challenging, as you essentially work with what could be called the fundamentals of art: line, form, and colour. Would you agree?

IK: In fact, at the time, I did not have any precise direction, or plan, when it came to making art. Today, however, I have a better vision of the art world, how it could be summarised, and how artists coexist. As I see it, there are two types of artists: the conceptual ones and the others like myself, using colour and line, and who could be qualified as ‘academic’ artists. I firmly believe that I was made to be part of the classical artists’ world more than any other group. I felt there was more potential and I could achieve more with this type of art.

AAN: Relying on these three elements, over time you have managed to achieve a very rich narrative. How did you go about that?

Izumi Kato: As I began painting, my work was about conveying hope. Why was that? One needs to take a closer look at the art curriculum in Japan, where there is a strong emphasis on copying, in a hyper-realistic way, everyday items so they look like photographs. We are being taught that this is the basis of painting. I did not share that view at all, and had a radically different approach. Let us take the example of a child: without any guidance, it will draw dots, round shapes, or graffiti. Alternatively, if we move into a more meticulous direction, we end up with something that looks like a photograph. However, today, there are cameras for such a purpose, and I therefore see no need to follow that route. I wanted to paint, even though I realised I could not get back to being the child that I once was.

That did not prevent me from coming up with a way to combine the rudimentary tools of line, colours, and dots, while also integrating human forms. Little by little, through this continuous dialogue with painting, my work started to evolve. Also, over time, I began to add more colour, with the human forms being now much more concrete than they used to be. My intention is not to deliver any kind of message, or to explain anything. I complete pieces following a creative process, always making sure the viewer looking at them can open their imagination to all sorts of things. Therefore, some people may recognise a story, while others may feel it is about an extra-terrestrial. I get all kinds of comments.

AAN: Within the shapes you depict, there is a very rich content that anyone can interpret as they please, depending on their imagination, their past, their experiences, etc. The overall shape seems like an envelope with a content that remains completely free.

Izumi Kato: Yes, exactly. That is the ideal scenario and is precisely what I want to accomplish.

AAN: It is interesting to see that with nothing very representative of the ‘envelope content’, all the human-like shapes have a strong presence, with a lot of charisma. It could almost be an ode to the human being. How do you see it?

Izumi Kato: a beautiful comment! I complete such pieces because I myself am interested in human beings, with a creative process based on colour, line, and shape. I place all the information within the piece, leaving ample room for the viewer’s interpretation. I feel this is the culminating point of the work.

AAN: What is your approach when facing a blank canvas?

Izumi Kato: creating and completing a piece, I am only in the act of painting, not trying to explain anything. But ultimately, after finishing a piece, I hope that there will be someone who reacts to it, who reflects on it. Strangely enough, I manage to accomplish this result without intentionally wanting it.

AAN: Within your practice, with painting, sculpture, and installation, what do you consider the actual starting point of your practice?

Izumi Kato: starting point is always painting and everything else derives from that.

AAN: A number of your pieces are based on fabric. How do you go about selecting it?

Izumi Kato: I create soft pieces based on a variety of old fabrics. For example,

I have used fabrics based on an old indigo-dyeing process popular in Japan, fabrics from Mexico, or textiles I found in France. Basically, the works in fabrics, or in stone, are completed through materials I find locally, depending on where my projects are taking place. The advantage of the fabric pieces is that I can install them in different ways, with a position according to my liking – a character can either be presented seated or standing, giving me a lot of flexibility.

AAN: When it comes to selecting stones for your pieces, is there some similarity with the way you choose the various fabrics, for example, from different areas, reflecting the place?

Izumi Kato: Yes, indeed. With regards to the stones, the key element is their shape, as I am combining them. When choosing them, I immediately wonder whether they will allow me to bring to life certain images I have in my mind. Ultimately, for the stones, I am not paying that much attention to local issues. In the case of fabrics, however, I visit various markets, which is something I truly enjoy. I am very receptive to the atmosphere of these markets. For example, the fabrics included in the exhibition in Paris were acquired at the market in Clignancourt. Some dealers have a whole variety of old fabrics, and I am eager to hear from them where and how they were used. That is always a wonderful moment, even though it has no direct impact on the final piece.

AAN: For some of your pieces, it is difficult to determine whether one should acknowledge them as sculptures or paintings. How do you see it?

Izumi Kato: Considering the nature of my work, it is hard to say whether a piece should be called a sculpture, a painting, or something else. For the stone pieces, for example, I assemble them, paint and sign them, so perhaps they could also be called paintings? It is difficult for me to identify to which exact category something belongs. What is nevertheless clear to me is that I enjoy painting and my goal for the future is to complete interesting and challenging paintings. That is fundamental. I want to complete good, and even extraordinary, works. Therefore, I will do whatever it takes for me to complete such paintings in the future.

AAN: As for the stone sculptures, how are they assembled?

Izumi Kato: For the vertical ones, if they are large, they are assembled through an iron rod, but if the piece is small, then the stones are on top of one another, and they are glued. If the stones are horizontally on the floor, then they are just placed next to one another.

AAN: Within painting, you highly value ancient cave paintings. Do you see yourself in the continuity of certain artists or movements?

Izumi Kato: In fact, when we look at ancient paintings, we are capable of having a dialogue with these pieces. Basically, the medium allows the information to be transmitted, with time having no importance. When I see cave paintings, I feel something very powerful. On another level, when I see Van Gogh’s work, I also have a very strong response, and I believe there is a bond with these pieces. It is the same with the work of Francis Bacon. These are paintings one can truly say are interesting works and I feel close affinities with these artists. Without sounding pretentious, perhaps I am the continuity of these artists? Perhaps, I am in the continuity of a broader tradition, at the other end of the cave paintings?

AAN: Presently, with the pandemic affecting the calendar of the art world, art is often experienced through social media. Do you find that to be a satisfying alternative to galleries, museums, fairs and biennales?

Izumi Kato: Today, with Instagram, times have changed. In earlier times, one had to be a professional in order to be on television. Today, each and every one of us can start making their own publicity through that type of social media. I am not criticising it: it is all right and it is even a good thing. However, it is a tool and the question is, how should we use it? Personally, I would not want to get known or get publicity through the wrong channels. The more people see works on Instagram, the more they come to my exhibition, realising it has nothing to do with what they saw on the screen. Therefore, one comes to the conclusion of why we need art. Let us take an example and try the following experience: looking at art works, at video, one has the opportunity to discuss the pieces, react to them, think about them. Finally, such experiences are necessary for the human being within society and are part of what makes life interesting. In my opinion, that is most likely the purpose of art. Even with nature, one constantly needs to observe it as it is in constant flux: if it rains, we need to make sure not to get wet, or one needs to pay attention not to fall over cliffs. In order to live and survive, we are constantly in the process of thinking, reflecting, defining new ways and strategies. Therefore, to make sure that all these faculties do not decline, we always have to stay sharp, and art allows us to do just that.

AAN: After graduating from art school, you deliberately put the brush aside in order to work directly with your hands, or sometimes, with a spatula. What limitations did you encounter in regard to the traditional brush?

IK: Perhaps, I was simply not good enough handling the brush. Basically, when I was working with the brush, I ended up creating works that anybody could have completed, and I could simply not obtain the line I had imagined. The moment I started using my hands, I managed to work in a much more detailed and meticulous way. For example, when wanting to graduate shades, I obtained a result I could never have achieved with a brush. Why is that? Because paint is made from tiny particles, and working with my hands, I can better control them. Contrary to the brush, it is far more homogenous, and with a spray, it is even more homogenous. Therefore, the tool that I find most fitting is the hand simply because it is how I can achieve the result I envision in my mind.

AAN: You keep two studios: one in Tokyo, and one in Hong Kong. With the present political uncertainty linked to the situation in Hong Kong, are you planning on keeping that studio?

Izumi Kato: Right now, I cannot go to Hong Kong as for the moment foreigners are not allowed to travel there. There are some unfinished works in my Hong Kong studio, which will have to wait until the situation gets better. Tokyo remains my primary studio, while I rent the one in Hong Kong. Should the political situation in Hong Kong remain uncertain, or get worse, I am not ruling out giving it up.

AAN: It is unusual for an artist to have two studios in Asia. What prompted you to select Hong Kong over London, or New York, for example?

Izumi Kato: The first reason was because my Paris dealer, Emmanuel Perrotin, also had a gallery in Hong Kong, and therefore, a professional connection was already established. In addition, I thought that, in a way, Hong Kong was at the centre of Asia, which encouraged many Western galleries to have a branch there. Also, the Chinese like painting and being in Hong Kong, one has the opportunity to see painting from all over the world without travelling to Europe, or the US. That makes it a marvellous environment for anyone interested in art. As an artist, this is something very positive and considering Hong Kong, its situation is quite different from the one in Japan. Hong Kong is very dynamic, whereas Japan feels very static, with nothing exciting happening. For me as an artist, Japan is very convenient and it is pleasant to live there, but I haveto admit that it has become slightly boring.

AAN: You are referring to Japan’s environment as being too static for an artist? Can you elaborate as from the outside, Japan still seems dynamic?

Izumi Kato: One of the major problems is that the majority of people is opposed to changing things that would require reforms. It is a common pattern that overall people dislike change. That explains why on a political level, things never change, and why there is very little transformation. In addition, as it is an insular country, it is an unwritten rule that people have to have the same appreciation of things: if the majority, or unanimously, people claim something is good, then one has to agree that it is good. In that sense, the pressure in society is immense.

AAN: Articles about your practice frequently associate your work with the Japanese Pop Art movement. Do you agree with that statement?

Izumi Kato: I have mixed feelings about it as part of me agrees with that statement and part of me does not. In Japan, people from my generation tended to have many children within one family. Therefore, manga and animé were part of the main culture and were extremely popular. Using that line of thinking, art was rather considered a sub-culture, and I realise personally I also hold certain Pop features. That being said, I do not quote Pop Art in my work as some other artists may do. As I indicated earlier, I consider myself to be a very academic painter. That is why I only partially agree with that statement

AAN: When you say ‘academic’, do you mean an artist whose work is based on colour, line, and form?

Izumi Kato: Yes, exactly. An artist who struggles with these elements.

AAN: In which direction do you see your work evolving?

Izumi Kato : I firmly believe my work is still improving, even though I do not have a precise idea as to how it is going to look. I want to be free to use any kind of material to keep my work evolving, and create pieces that are different from anyone else’s. In order to achieve that, I need to keep practising and experimenting in my studio on a daily basis. I am very happy I have the chance to work in Japan, as well as abroad, as it gives me a certain balance and perspective, from which my work benefits a

great deal.

AAN: Looking at your work over the past 20 years, you seem to keep reinventing yourself rather than pursuing an approach that has proven to be successful.

Izumi Kato: If one does not act in this way, then indeed, it is sheer repetition, and I do not think that is a good thing for any artist. For example, as an athlete, one constantly wants to match or even break one’s previous record. Similarly, I want to keep that motivation and I am glad if people actually see and appreciate that aspect of my approach.

AAN: Compared to your earlier work, the colour palette has evolved a great deal. Today, what is your approach towards colour?

Izumi Kato: Colour is just colour. Monotone works in black and white, or only red, are very easy to paint. It is gets much more complex when combining various colours, which makes it difficult to complete interesting work. Personally, I like challenges, and I prefer making complicated things instead of easy ones. Of course, I may complete something in monotone, but as it is easy, it does not evolve or improve. That explains why I prefer using a variety of colours, thus increasing the quantity of information presented.

AAN: Your works seem to bring together extremes: very serious versus humour, life versus death, real versus unreal. We therefore have two universes that are balanced next to one another. Do you agree?

IK: I could not agree more. To me, in order to be successful, a painting needs to bring together antithetical information like life and death, strength and weakness, hot and cold, etc. To me, it is wonderful if people perceive these aspects within my work.

AAN: You have also been using vinyl as a medium. How did that come about?

Izumi Kato: As you know, soft vinyl is a Japanese technology. Usually, this material is used for children’s toys and, in my case, I became interested as a friend of mine was manufacturing soft vinyl toys. At some point, he suggested we work together. To me, soft vinyl was a simple day-to-day material that I was familiar with – as a child, I used to play with such toys, mainly soft vinyl monsters. Instinctively, I thought I could use this material for my work. As we decided to collaborate, we experimented, creating some prototypes of very small soft vinyl objects that are also commercial. Then, we created larger pieces and, when staging an exhibition, we recreated a limited edition of small sculptures (edition of 100). I thought it would be interesting to have the dolls available at a store in conjunction with my exhibition. So now I sell them, but I also use them in my work.

AAN: You used to give titles to your works, which you eventually stopped doing. Why is that?

Izumi Kato: There are two reasons. Firstly, as there is a large quantity of works, I am not always able to find a relevant title. Secondly, if I give a title to the work, people are strongly influenced by it and look at the piece according to the title. For these two reasons, I stopped creating titles.

AAN: Do you still own some of your early works?

Izumi Kato: In fact, I hardly have any of them – perhaps just a few. As I was totally unknown as I came out of art school, I sold most of them to support myself. I threw some away and some have been lost, which is very unfortunate.

More images can be found at Perrotin Gallery, Paris