Hokusai Beyond the Great Wave is the extensive exhibition organised by the British Museum on the life and work of Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849).

‘Ever since the age of six I have had a mania for drawing the forms of objects. Towards the age of fifty I published a very large number of drawings, but I am dissatisfied with everything which I produced before the age of seventy. It was at the age of seventy-three I nearly mastered the real nature and form of birds, fish, plants etcetera.

Consequently, at the age of eighty, I shall have got to the bottom of things; at one hundred I shall have attained a decidedly higher level which I cannot define, and at the age of one-hundred-and-ten every dot and every line from my brush will be alive. I call on those who may live as long as I to see if I keep my word’ – signed, formerly Hokusai, now the Painting-Crazy Old Man. From One Hundred views of Fuji, translated by Harold P Stern.

Hokusai Lived Until He Was 90

In fact Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849) lived until he was 90, in an era of Japanese society when the average life expectancy was forty-five. Clearly, he fervently believed that his art and accumulated life experiences were constantly burnishing his technical skill, as well as the more indefinable transcendent aspects of his work, and would improve with age.

He was always so exacting in his demands on the block cutters for his prints, with ever more intricate details, since he wanted his drawn lines to be reproduced as faithfully as possible, that there were complaints from publishers, since inevitably – fees were perceived as exorbitant for such detail and expertise.

Hokusai Was Told: Your Pictures Are Too Detailed

Hokusai was told: ‘Your pictures are too detailed. They are not pictures any more. Do something about it!’ Hokusai’s response was: ‘If your technique is clumsy to begin with, as you grow older, it will very quickly get worse … Day by day in my old age, I am developing my technique by building on my past failures. Even though I am nearly eighty, my eyesight and the strength of my brush are no different from when I was young. Let me live to be a hundred and I will be without equal.’

In 1848, the year before his death and the publication of his final painting manual, Picture Book: Essence of Colouring the signature on one of his last prints – Pine Trees and Full Moon, includes: ‘eye glasses not needed’. And, indeed, the textures of the tree bark and the individual pine needles are incredibly intricately drawn.

British Museum Exhibition on Hokusai

The British Museum’s seminal exhibition this summer is Hokusai: Beyond the Great Wave, focusing on the last 30 years of his life from around 1820 to 1849, when not only was he prodigiously productive, but also created his greatest works of art. He is not only widely acclaimed as Japan’s greatest artist, but his iconic print The Great Wave, circa 1831, is as world famous as Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus or Andy Warhol’s prints of Marilyn Monroe.

As the Hokusai scholar Roger S Keyes points out: ‘The Great Wave, though compelling as it is, is only one of (some) 3,000 colour prints that Hokusai designed during a 70-year career … In addition, he drew illustrations for over 200 books, frequently in sets of many volumes. Hundreds of drawings and nearly 1,000 paintings also survive. Paintings were a major focus of the artist’s work in his final years, particularly in his last decade, the 1840’s.’

Hokusai was also a highly literate man, associating closely with writers and poets, illustrating many of their books. Furthermore, he was a prolific writer, ‘producing stylish fiction, light verse, riddles and educated prose, including brush drawing manuals and a treatise on colour’.

Hokusai’s Paintings

In particular, the paintings rather than the prints of these last 30 years are awe-inspiring, the apogee of his genius as an artist, transmitting his personal beliefs and are also explored in Hokusai Beyond the Great Wave. As the Director of the British Museum, Hartwig Fischer points out, the exhibition takes us literally and metaphorically ‘beyond the Great Wave, to explore Hokusai’s artistic and spiritual journey during his last three inspiring and innovative decades.

The British Museum purchased its first Hokusai print in 1860,’ and in 2008 rounded out its collection of other Hokusai works by the acquisition of ‘a fine early impression of the Great Wave print’. Hokusai: Beyond the Great Wave presents the fascinating story of an artist constantly innovating, overcoming the challenges of old age and often precarious life circumstances to produce sublime art. ‘The exhibition demonstrates how his vision evolved from the more commonplace images of his early work to an increasing emphasis on the spiritual significance of this and other worlds in his later work.

The Import of Prussian Blue Pigment into Japan

He used deep perspective and imported Prussian blue pigment in The Great Wave adapting and experimenting with European artistic style. A rare group of paintings in the exhibition, lent by the National Museum of Ethnology, Leiden, show considerable European influence. They were commissioned by employees of the Dutch East East India Company around 1824-1826. Whether the adoption of aspects of European style indicates Hokusai’s acumen as a commercial artist, or genuine inspiration, is a moot point. One of the European techniques he adopted was the use of shading, animating his subjects, in particular – still lives, plants, birds and animals.

Hokusai’s Life and Work

Hokusai’s life and work are characterised by his generous, all-embracing view of humanity. He celebrates people from all walks of life, exemplified by his last great print series, begun when he was 76, titled One Hundred Poems by One Hundred Poets, Explained by the Nurse. She is an uneducated woman whose wisdom and knowledge of life are apparent in the prints, along with her comic misunderstanding of some of the puns in the poems, with hilarious and sometimes bawdy results.

The Nurse’s interpretations offer a parallel focus on reality, as opposed to that of the poets. Hokusai’s woodblock prints and drawings for the series have greater richness of colour and more wealth of detail than the prints of any other series in this large format, and the collection has become an integral part of Japanese culture and life.

The Subject Matter Relates to Spiritual and Natural Worlds

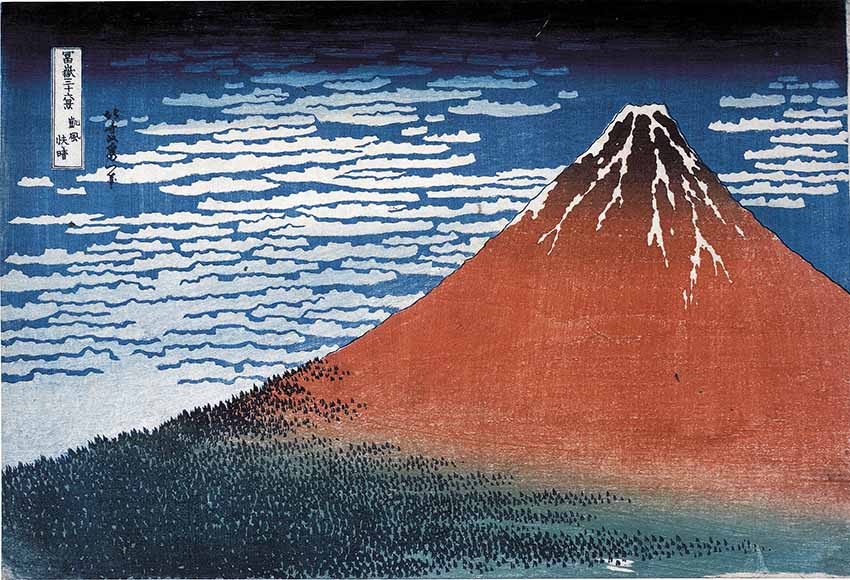

Hokusai Beyond the Great Wave shows that Hokusai’s work is both dramatic and uplifting, yet resonates with comical, everyday aspects, as well as empathy for the human condition. The subject matter also relates to spiritual and natural worlds, the later work in particular focusing on natural subjects, such as flora and fauna, and landscapes like the wave pictures and his incomparable studies of Mount Fuji. For Hokusai, the volcano held spiritual significance, as a sacred source of water and life, and as a symbol of immortality.

It also represented a revered source of longevity, with which as we have read, he so identified. He believed ‘in Mt Fuji as an enduring constant, through which it might be possible to transcend the present,’ writes Angus Lockyer, Lecturer in the Department of History at SOAS University of London. ‘Mt Fuji not only occupied space in the physical landscape, it provided a spiritual anchor in relation to which the world was configured and a viewer could find their place… In the book One Hundred Views of Mt Fuji (3 vols, 1834-49), he explored not only the natural but also the spiritual dimension of the mountain.

Here and elsewhere, not least in his fascination with water, he returned repeatedly to the umbilical connection between stillness and movement – between the fixed and eternal truth of Fuji, for example, and the world of unceasing change. By doing so, he sought to reveal how nature itself provides a connection to the divine.’

The Thirty-Six Views of Mt Fuji

An earlier publication of around 1831-33 of the print series Thirty-Six Views of Mt Fuji had helped revive Hokusai’s career after personal challenges in the 1820s. Roger Keyes characterised this first series as ‘the miraculous daily return of colour to the world.’ And the series is one of the highlights of Hokusai Beyond the Great Wave.

In 1834, the first volume of One Hundred Views of Mt Fuji was published, ‘one of the greatest books ever’ writes Timothy Clark, curator of the exhibition. ‘The sacred mountain is shown in a dazzling range of guises and inventive compositions. His block-ready drawings were interpreted in unparalleled fine cutting by a team led by the artist’s block cutter of choice, Egawa Tomekichi’ (who, no doubt, charged an appropriate fee).

Hokusai’s Last Image of Mt Fuji

In Hokusai’s very last image of Mount Fuji, painted in the final months of his life, a dragon rises triumphantly from an ominously dark cloud above the sacred mountain. The dragon is one of the mythological creatures aligned with a variety of deities which coexist with Hokusai’s lifelong faith in Nichiren Buddhism, which as Timothy Clark points out: ‘Served to keep Hokusai spiritually focused and attuned, he believed, to all the manifestations of creation.

Many other powerful spiritual talismans were mobilised in his late artistic repertoire, vehicles for expressing this unique mix of personal beliefs. These included powerful mythical beings such as Shoki, the powerful demon-queller, Zhong Kui,’ who was painted twice in red on silk in 1846 to protect the purchaser from misfortune and disease – especially smallpox. ‘He also painted holy men such as Nichiren (1222-1282); and proud solitary animals, birds and mythical creatures – cormorants and eagles, tigers and dragons, Chinese lions and phoenixes. They are all, in a sense, self-portraits of Hokusai who wanted proudly and forcefully to communicate with us. You and I commune, he insists, through these extraordinary images.’

Hokusai Struck by Lighting at the Age of Fifty

Around the age of fifty, he was struck by lightning, which changed his life completely. In 1812, he left Edo, travelling to Kyoto and other regions. A year later he returned to Edo, and changed his name to Taito, which translates as ‘Star-blessed.’ This infers that after the lightning strike, the North Star which had been the principle focus for his religious devotion for decades, had saved his life.

Hokusai Changes His Name Again

In 1820, Hokusai changed his name again to ‘Itsu’, meaning ‘become one with creation’, although he was not to know how troubling and arduous the next decade was to be. His drawing became a voyage of discovery ‘becoming one with his subjects’, echoing his name. In 1834, he changed his name yet again, pronouncing himself to be ‘Manji’, meaning ‘everything’, ‘always’, or ‘all.’

The signature at the back of Volume One of the One Hundred Views of Mt Fuji series was ‘Brush of Manji’, old man crazy to paint, changed from the former Hokusai Itsu, aged seventy-five’. The symbol for Manji is a reverse swastika, an ancient auspicious symbol in India and Buddhism. Its sound means ‘ten thousand things’, or ‘everything.’

As a Commercial Artist

Hokusai had always needed to be a commercial artist, in the sense of making a living. An advertising flier of 1834 included a somewhat jaded comment from him: ‘I have enjoyed painting since childhood. Yet for more than seventy years now, I have not been able to fathom its depths. Over the years, I have attended calligraphy and painting parties, a hundred, maybe a thousand times. Personally, I have got bored with their games and these days I try to avoid them.’ He had been trained in the popular ukiyo-e style, the art of the ‘floating world’, featuring geishas, kabuki actors and poets. But later he eschewed the literary parties and social world in which he had been a leading figure.

Hokusai’s Marriages

When he was a child Hokusai was adopted by a mirror-maker supplying the court of the shogun of Edo (present-day Tokyo). His was not an easy life. Marrying young, his first wife died in 1785, when he was just 25, leaving him with three children. Then he married again, his second wife bearing two or three children, and dying in 1828. The 1820s were a harsh time for the family, of illness and loss.

A beloved daughter died in 1821, and then serious gambling debts accrued by an errant grandson fell on Hokusai’s shoulders. After dire spells of poverty, he achieved some success by gaining more patrons, galvanising commissions for hundreds of prints.

His third daughter, Eijo, herself an accomplished artist (art name Oi), left a failed marriage and came to care for her ageing father who was living in very modest accommodation, and also to work alongside him. Timothy Clark suggests the contribution Eijo made to Hokusai’s work in the last three decades of his life: ‘The prime trait (of her work) is an intricately detailed style that features modelling highlights, shading and darkness in a manner that would have been considered ‘European’ in the contemporary Japanese context’. Hokusai’s work certainly reflects this influence, as we have seen with his use of shading in his commissions for the Dutch East India Company.

In the Late 1820’s Hokusai Suffered a Stroke

In the late 1820s Hokusai suffered a stroke that permanently affected his drawing. ‘Although he recovered and taught himself to draw again, he never regained his former fluency and became more dependent on Eijo,’ writes Roger Keyes. In 1834, fire swept through their neighbourhood, and although he and Eijo were able to escape with their lives, tragically the wooden cart containing all Hokusai’s sketches, supplies and reference materials was immolated.

This was the cart they had dragged from one lodging to another, father and daughter described as almost beggars. That same year, 1834, he went into hiding (senkyo), staying in the coastal town of Uraga for about two years. Timothy Clark clarifies the reasons for this self-imposed exile: ‘One of his children broke the law …, he was trying to avoid the problems arising from the dissolute lifestyle of his grandson … who had already caused chronic problems in the late 1820s. In addition, a picture he drew contained something that infringed public morality; (and) he was overwhelmed with debt.’

There was also a devastating crop failure and famine in 1836, which caused thousands of deaths. In such appalling conditions people stopped buying luxury items such as colour prints and illustrated books.

Ever responsive to the demands of the market, Hokusai came up with a necessarily limited solution, gathering together all sorts of available paper, on which he painted landscapes, plants, flowers, trees and birds. He added covers to these, making them into folding albums. Since he was already so well known, a few aficionados began to buy them, and in this way he and his family just escaped starvation.

More Economic Disasters

Yet more economic disasters followed, Hokusai and Eijo moving their rented accommodation – 93 times – by 1848. From autumn to spring he wrapped himself in a lice-ridden quilt. A biographer describes a corner of one of these rooms as being piled with rubbish, discarded wrappings of charcoal and food. He records that each morning Hokusai would draw a Chinese lion or lion-dancer on a small piece of paper and throw it out of the window – to ward off evil.

By 1847, two years before Hokusai’s death, a letter written to a pupil indicates the practical challenges he was facing. He asked for a loan noting ‘because my infirmity has recently returned.’ But still he kept working. In fact,that year – 1847 – he was almost as productive as in any other year during his eighties.

He and Eijo received financial support from a wealthy saké brewer, Takai Kozan, who was instrumental in securing significant commissions for Hokusai, including two magnificent ceiling panels of wave subjects, which are part of the British Museum exhibition. Other patrons in Edo also acquired works in the artist’s last years.

Hokusai’s Last Words

Finally, in 1849, after a short illness, a doctor pronounced that no medicine could help him. Hokusai’s last words were: ‘If heaven will extend my life by 10 more years…’ then after a pause, he added: ‘Then I’ll manage to become a true artist.’

Hokusai’s Heritage

So what is Hokusai’s heritage? He was preoccupied with passing on his ‘divine teachings’, as he put it, to his pupils, to craftspeople, and indeed – to the whole world. He published several brush-drawing manuals, including Hokusai manga (Hokusai’s sketches) in 15 volumes. Just two years before his death, he finished working on the painting manual Picture Book: Essence of Colouring.

In a postscript to Volume One, he expresses his wish to transmit to a wider audience his practical experience accumulated during his lifetime. After specific instructions on the method of preparing certain pigments, illustrated examples are given of how to colour about a 100 different motifs, many of them in the paintings of his last years. This was his first systematic attempt to teach his painting technique.

The Very Last View of Mt Fuji

Surely his very last view of Mount Fuji, painted in his final months, with the dragon rising above the sacred mountain, is a symbol of Hokusai’s vision of immortality. Actually, he did achieve immortality in a practical sense as a source of inspiration for the Impressionists and many other artists too; and as a catalyst for Japonisme, the cultural movement in Europe galvanised by admiration for the art and design of Japan.

In just half a century after his death in 1849, in 1900 a major solo exhibition of his work was staged in Tokyo, and collectors in Japan and then abroad, were actively buying his work. As we have seen, the British Museum bought its first Hokusai print as early as 1860 and it is on show in Hokuai Beyond the Great Wave.

Hokusai is now viewed as one of the world’s greatest artists. On the title page of his drawings titled Lives of Famous Generals of Japan and Record of Shoguns of Great Japan, is an inscription. ‘These pictures were never made into blocks. They are a masterpiece for all ages’.

BY JULIET HIGHET

Hokusai: Beyond the Great Waves runs at the British Museum until 13 August. It closes from 3 to 6 July for a partial change-over of exhibition, due to conservation concerns. Catalogue available.

More information on the events organised around the exhibition can be found on britishmuseum.org