There was a moment of high drama at the conclusion of my interview last November in Shanghai with internationally renowned Chinese video artist Zhang Peili. Suddenly, he realised he had lost his ID card, a critical piece of personal documentation that in China must be carried at all times and which facilitates such things as buying a train ticket, what you can do, and where you can go. Evening was drawing in and Peili was anxious to return to his home in Hangzhou at the conclusion of the interview. Time, it seemed, was running out fast. Pockets were searched and bags upended, as barely suppressed panic ensued. But there, buried in the pile of clutter on the table, was the lost ID card. All was well.

In late 2019, we had talked at Ren Space, a small contemporary gallery tucked down an alley in Shanghai’s cultural heritage precinct of Longmen Cun. The building dated from 1935 and with its restored elegant Art Deco interior, it oozed charm. The gallery had devoted its entire exhibition space over three floors, to Peili’s solo exhibition, The Annual Report Card of OCD, a glorified self-portrait made up of high-tech robotically carved sculptures of his bones and several organs. The exhibition marked a significant moment in Peili’s decades- long career, which has embraced painting, photography, installation, performance, moving-image work, kinetic installation and sound work, with exhibitions around the world, too numerous to mention. The Annual Report Card of OCD marked the first time Peili had turned to pure sculpture.

New Space Exhibition in 1985

Zhang Peili was born in 1957 in Hangzhou, not far from Shanghai, in Zhejiang Province. He graduated in 1984 with an MFA in painting from the prestigious Zhejiang Academy of Fine Arts (now the China Academy of Art). He participated in the radical 1985 New Space exhibition that rebelled against academic and aesthetic tastes of the day, and from 1986-87 was a member of the Pond Society, which staged performative avant-garde interventions around Hangzhou as a reaction to the current art conservatism that was manifest in socialist realism. In 1987, he painted X? a series of 141 large paintings of latex gloves, in flat monochrome colour that possessed an almost sombre monumentality and which, with their obsessive sense of repetition and graphic simplicity, bordered on banality, a trope that he explored in subsequent video works.

Peili abandoned painting in 1988 after being asked to create a video work for the Huangshan Conference on Modern Art that laid the foundations for the ground-breaking China/Avant-Garde exhibition that took place in February the following year in Beijing’s National Art Museum of China. On borrowed video equipment, he filmed his latex gloved hands over three hours, as he repeatedly smashed a mirror and then glued the shards back together, before smashing it again.

The video’s length was determined by the fact that it was the longest video tape available to Peili, while the name, 30×30, referred to the size of the mirror. Its tedious repetition would bore those who had the stamina to watch, but demonstrated Peili’s enduring fascination with the monotony of repetition and how it seemed to articulate the passage of time. It also confirmed in him the realisation that, in his words, ‘an artwork itself was not the most important thing but that it was the process, that mattered’. ‘For me the most basic motivation or departure point for making my video work, is monotony and meaninglessness,’ he continued enigmatically, as our conversation slowly began to unfurl.

Zhang Peili: The Importance of Video

For Zhang Peili, video was able to convey the passage of time in a way that painting could not. Also pertinent historically, was the fact that 30×30 subtly critiqued the hypnotic banality of popular television, and the pervasive nature of political authoritarianism, in a country dealing with the rapid relaxing of economic regulations, social transformations and personal freedoms, under Deng Xiaoping’s reforms. 30×30 was a seminal and ground-breaking work, and is now widely regarded as the first video artwork in China, and earned Peili the sobriquet, ‘the father of video art in China’.

This work was quickly followed by Document on Hygiene No 3 (1991) a two-hour-long, silent, video that showed Peili repeatedly wash a live chicken. Over the course of the video the distraught chicken became complacent and subdued. Recently it was included in the Guggenheim 2017 exhibition Art and China after 1989: Theatre of the World, in a shortened 20-minute version, the two-hour version perhaps considered too repetitive and boring for viewers. Repetition and boredom however, proved a critical component of Peili’s approach to video making. He wanted the audience to become bored and ultimately, disturbed, and he wanted them to become conscious of the passage of time.

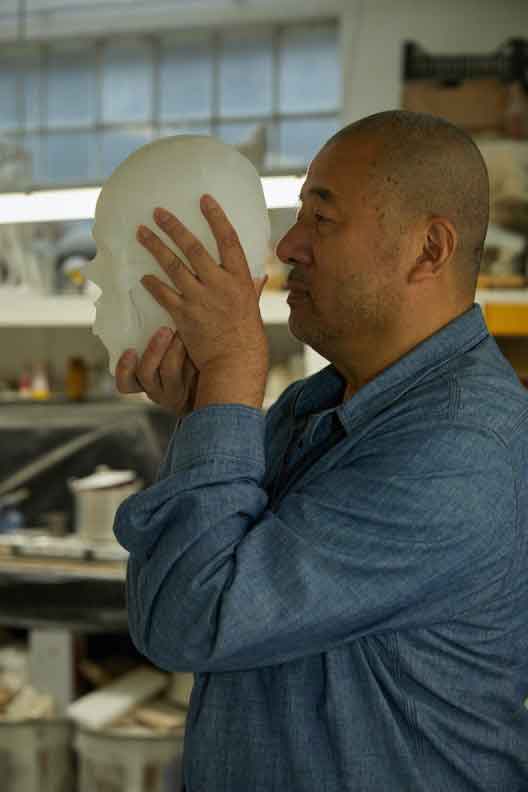

Life-size Marble Bones of Zhang Peili’s Body

The recent Ren Space exhibition featured life-size sculptures of the bones in Peili’s body – all 206 of them – laid out in various configurations as well as the complete skeleton being laid out flat, on a gurney-like table, in a darkened room. Sculpted robotically in Italy from Carrara marble, the bones possessed an eerie presence. Each part of his body had been meticulously scanned using MRI medical imaging in China and then carefully carved from Carrara marble in Italy using advanced automated carving techniques.

The project took two and half years in the planning and execution. There were many difficulties along the way, Peili said. He had to learn the techniques of polishing, finishing, carving, and visited many places in Italy to be inspired by classical sculpture. Some of the bones were carved from marble, some onyx and some travertine, each stone offered unique characteristics, he explained. One of Peili’s skulls – there were multiple skulls on show – was carved from white Mexican Onyx and possessed a dazzling translucence. ‘I favoured marble. It is an elegant, classical and sublime material,’ he stated. It was all rather chilling and macabre, a memento mori.

Moments before I arrived at Ren Space, Peili had just finished an interview with Chinese television and was sharply dressed in grey slacks with a black zip-through leather jacket over an untucked, patterned, business shirt. He appeared tired and irritable. Even as he was faultlessly courteous when he greeted me, it soon became apparent that the questions I asked were ones he had answered countless times before and his countenance grew dark and his eyebrows furrowed.

In the alley outside, children played in the warm autumn air, electric motorbikes purred and men cursed. Inside the gallery, a distinct chill descended. However, gradually against this sound-scape of life the stilted question-and-answer session unexpectedly shifted a gear and a real conversation began to emerge, me speaking through an interpreter and Peili answering in Mandarin, although it was obvious he understood some English, having spent 10 months in New York in 1994-95.

Upcoming Exhibitions

I was not surprised to learn that Zhang Peili’s exhibition calendar was bursting at the seams. He was in the throes of preparing for a group show – Move on China 2019 – at HOW Art Museum (HAM) in Shanghai with long-time artist friends, Feng Mengbo and Wang Jianwei – equal giants in the Chinese conceptual art firmament. Peili’s installation at HAM, Live Report: Hard Evidence No 2, showed the burnt and blackened remains of redundant technology; computer monitors, keyboards, television screens, portable radios et all, arranged on a circular plinth like a technological graveyard. To one side a monitor played a series of stills from the earlier conflagration. A mutual acquaintance spoke of how Peili in recent years had become dazzled by the speed of technological development.

On the other side of town in the annual Art021 art fair, Peili had just installed his enigmatic, immersive kinetic installation, XL Chamber No 2, a container-sized windowless box with electric shutters that unpredictably closed and opened, and randomly trapped people inside. It was painted a seductive, and benign, duck egg blue. Adults inside looked alarmed and bemused as the shutters slid down, and trapped them inside. XL Chamber created a litany of Instagram moments, but it possessed a chilling silent narrative of lost freedoms, pre-emptory incarceration, and lack of control – tropes that had fascinated Peili, throughout his career – almost 20 years of which have been spent teaching new media art at the China Academy of Fine Art in Hangzhou, a department that he had established in 2003.

September Exhibition at UCCA, Beijing

In September 2021, there will be a survey show at UCCA in Beijing exploring his work of the previous decade. Peili is deliberately obtuse about explaining his work, preferring the audience to supply their own interpretation, as to what it means. The deep political undercurrents and the critique of social mundanity are obvious, and exist within a silent brooding existential framework. ‘I am often asked this question, but I never define my work. I never explain why I do this work. I believe when an audience enters the exhibition they have their own understanding. My work is not really about any specific things,’ he said.

Although currently obsessed with his sculptural project, he confessed to not having turned his back on painting, or video art. ‘I feel I still have a lot of possibilities. Yesterday I spoke with a curator from Pompidou Shanghai’. (Centre Pompidou Shanghai opened in Shanghai the week we spoke.) He continued, ‘She was curious about whether I would ever go back to painting. You never know in the future, I told her. But for now I will continue this sculpture series. Also I want to do some sound installations, maybe mixed with lighting. I already have something solid in my mind, and soon I am thinking that I will make a new video work. I will think carefully about this’. Peili was also thinking of a new form of teaching institution, but it is early days yet.

How did he feel when he held his marble skull in his hands? It was a tantalising thought, but he skated around the question. ‘The most exciting moment for me was when I understood I could actually create this project. Before that moment, I was not sure what was possible. Until then everything had been experimental,’ he remembered.

Zhang Peili Bone Sculptures

Zhang Peili dismissed the suggestion that his bone sculptures had been driven by contemplation of his own mortality. He insisted it was not a vanity project. He reflected quietly before replying. ‘After 2001 there were several unexpected deaths in my family. My father passed away, then my best friend, and then his mother. My uncle and aunty passed, too. All unexpectedly. One by one they all went. One day I decided to go to the temple to see the master to talk about death. He said, we had to have a peaceful mind regarding death. He said that when a baby is born it is a time of birth, which will ultimately lead to death. It is a normal part of life. Do not try and block out death, the master said. Since then my attitude to death changed. Everything becomes dust. This is the way,’ Peili stated with chilling finality.

In many ways The Annual Report Card of OCD was the ultimate three-dimensional selfie. In the darkened gallery, I felt as though I had stumbled on to the set of an absurdist drama, where the main denouement was an existential reckoning that pointed to the absurdity of life in general. Peili might prefer to call it the aesthetics of boredom – which he often defines as a central trope in his work – but by then I felt I had reached the limits of his endurance and he seemed more than ready to step out into life’s absurd reckoning, among the children playing outside, the motorbikes purring, and the old men shouting. As he walked off he clutched his Chinese ID card firmly in his hand, en route to the station and the high-speed train that would propel him at 300 kilometres an hour to his home in Hangzhou. Which, in Peili’s grand scheme of things, is no time at all.

LISTEN TO Zhang Peili talking about his work Endless Dancing shown at APT3 at Queensland Art Gallery, Brisbane, in 2018 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qUGVPyXQxOY

WATCH Zhang Peili’s 30×30, 1988, single channel video, 32’09’’ ( this is the beginning 5 mins) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dO8Uv_wDK0E