The Yoshida family’s printmaking legacy stretches over three generations. It began in the mid-19th century with Yoshida Kasaburo (1861-1894), who taught Western-style painting. Kasaburo’s artistic legacy continued with his daughter, Yoshida Fujio (1887-1987), who married fellow artist Yoshida Hiroshi (1876-1950), Kasaburo’s adopted son. This first generation of printmakers starting with Fujio and Hiroshi (a leading shin hanga artist) passed along their artistic practice to a second generation, their oldest son, Yoshida Toshi (1911-1955), and his wife Yoshida Kiso (1919-2005).

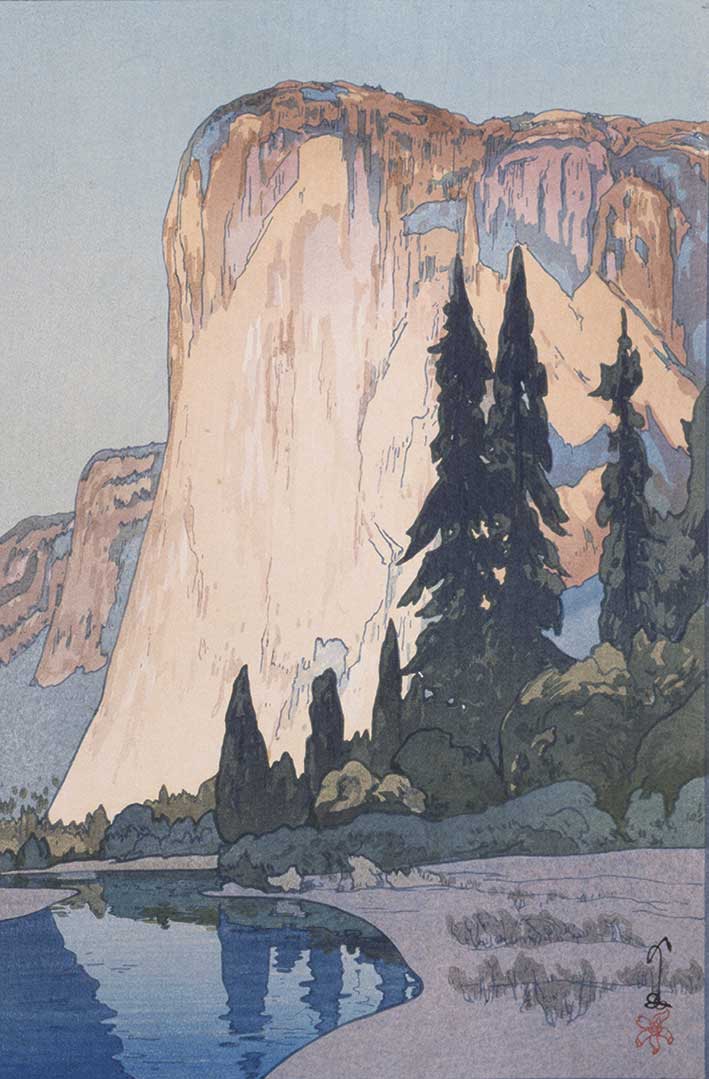

Shin hanga landscapes were quite different from their ukiyo-e predecessors. These prints offered an updated version of traditional prints, using Western concepts of space, light, and volume, combing the best of both worlds. Hiroshi was considered one of the most talented Western-style painters in Japan and had a number of successful exhibitions of his oils and watercolours in the US, which helped fund his travels. He had also become aware of the influence of Japanese prints on Impressionism and Post-impressionism in the West. He was also one of the few Japanese shin hanga artists to depict foreign themes.

The first new 20th-century print movement in Japan, shin hanga (new print), refers to the revitalisation of printmaking in the first half of that century. The opening up of Japan by the Western powers early in the Meiji era (1868-1912) brought about the decline of printmaking, as new techniques such as lithography and photography grew in popularity. Influenced by Western art, the shin hanga movement presented an idealised view of Japan while raising the quality of technical execution to a high level. Production focused more on subjects that appealed to both Japanese and Westerners, such as flowers, birds, and landscapes, represented in this room, than on some of the traditional themes featured in ukiyo-e prints, such as famous warriors and literary references.

The second great modern print movement, sosaku hanga, was inspired by Western practices and sought to enhance the status of engraving, the members of sosaku hanga wanted to make the artist aware of all the stages in the realisation of his works, without the intervention of specialised craftsmen, such as the engraver, or printer. Thus the mark made by the chisel on the block of wood also became the expression of the artist’s personality, as was the brushstroke of the calligrapher. In comparison with shin hanga prints, the result is often more raw, impromptu, with a sense of spontaneity. Unlike shin hanga prints, which attracted foreign buyers and were successfully promoted abroad, as was the case with Yoshida Hiroshi, sosaku hanga were mainly sold to a Japanese audience, through subscriptions, or art exhibitions.

Yoshida family prints tradition continued with Yoshida Toshi, Hiroshi’s son, was a noted shin hanga and sosaku hanga artist, who followed in his father’s footsteps. He was also known for producing realistic landscapes, but also developed his own style of print using imaginative abstract designs, and detailed portraits of animals in their environments. He travelled with his father for one year from 1930 to 1931, visiting India, Hong Kong, Shanghai, Malaysia, Singapore, Calcutta, and Burma. Later in his early adulthood, Toshi attended the Taiheiyo-Gakai (Pacific Painting Association) from 1932 to 1935, which had been co-founded by his father. In 1936, during the military dictatorship in Japan, Toshi lived in China and Korea, but eventually moved back to Japan to pursue his career.

After the Second World War (1939-45), Toshi embarked on his biggest trip, travelling to every continent, producing detailed sketches of what he saw and when he returned home, recreated these sketches and memories into prints and paintings. During his travels, he also showed in many exhibitions and lectured at various stops in Europe and the US.

In the 1950s, Toshi began to make larger abstract prints in the sosaku hanga manner without the help of his workshop, creating a series of abstract woodcuts influenced by his brother Yoshida Hodaka (1926-95). By the late 1960s, he had converted to abstract art in the sosaku hanga manner and went against earlier traditions of ukiyo-e and shin hanga.

Fujio’s and Hiroshi’s second son, Yoshida Hodaka, married an artist, named Yoshida Chizuko (1924-2017) and they continued to practice printmaking. Known for his surreal, abstract, and arrestingly colourful prints, Hodaka rebelled against the Yoshida family artistic style of realistic woodblock prints to forge his own path. His unique style of surreal landscapes and abstract forms was inspired by his globe-spanning journeys, photography, poetry, ancient art, and the inventive methods of contemporaneous art movements. Their daughter, Yoshida Ayomi (b 1958), represents the family’s third generation of printmakers and completes this multi-generational line of artists.

This London exhibition of Yoshida family prints features prints by Hiroshi’s and Fujio’s sons, Toshi and Hodaka, both of whom brought post-war abstraction to the Japanese printmaking process. Early on in his career, Yoshida Toshi followed in his father’s footsteps, depicting landscapes and cityscapes, but experimented with abstract prints after Second World War. The exhibition includes some of his most accomplished works, including Night Tokyo: Supper Waggon (1938) and Camouflage (1985).

Yoshida Hodaka was a leading printmaker in post-war Japan. In a break from his family’s established style, he expanded upon traditional printmaking and incorporated collage and photoetching into his practice. Like his father and brother, foreign travels influenced his choice of motifs, but he was also inspired by Pop Art, Surrealism, and Abstraction. Works such as Profile of an Ancient Warrior (1958) and Nonsense Mythology (1969) demonstrate his unique style.

Yoshida Chizuko, who married Hodaka, was a renowned artist and co-founder of the first group of female printmakers in Japan, the Women’s Print Association. Chizuko often depicted landscapes, nature, and traditional Japanese scenes, but she also explored aspects of abstraction and repetition. Her works were said to have connected popular art movements such as Abstract Expressionism and traditional Japanese printmaking. Highlights include A View at the Western Suburb of the Metropolis/ Rainy Season (1995) and Jazz (1954).

The exhibition of Yoshida family prints ends with a new site-specific installation of cherry blossom by Yoshida Ayomi, Hodaka’s and Chizuko’s daughter. The youngest member of the Yoshida printmaking family, Ayomi’s practice combines traditional Japanese printmaking techniques with modern elements, often utilising organic materials, and she has been exhibited at major international institutions. Ayomi’s immersive installation, a new work created especially for Dulwich Picture Gallery, explores the recurring theme of seasonality in Japanese art and is inspired by the cherry trees in Dulwich village, originally taken from the iconic site of Yoshino in Japan, famous for its cherry blossom.

Ayomi also found a surprising and very personal link to the exhibition, saying, ‘When I found my grandfather’s signature in the Dulwich Picture Gallery guest book, my heart skipped a beat. What an exciting and intriguing journey it must have been for Hiroshi, then an unknown painter and only 23, travelling from a country so far away. How proud he would be of this family exhibit of six, welcomed 120 years later at this wonderful museum’. (https://www.beicy.com/)

From 19 June to 20 October, 2024, Dulwich Picture Gallery, London, dulwichpicturegallery.org.uk