‘Yoko Ono: Lumiere de l’Aube’ at the Musee d’Art Contemporaine, Lyon

“Purge the world of bourgeois sickness, ‘intellectual’, professional & commercialized culture.” So reads the first line of George Maciunas’ Fluxus manifesto of 1963. This vitriolic scrawl came as a response to many things, among them, the increasing power of the art market, institutionalised art criticism and the white male-dominated Abstract Expressionist movement that had popularised the 1950s. The word itself connotes the unfixed and rational irrationality – properties that in Maciunas’ eyes could serve as an antidote to the prescriptive state of art-making in the mid-twentieth century. Maciunas and the large group of artists and writers with whom he associated wanted change, but one that would continue indefinitely, eternally self-redefining. To him, the principal tenets of flux – movement, flow and chance, were the only things that could and should be certain in life. Principally, Maciunas saw this philosophy as the means of effecting long-term epistemological shifts. The manifesto also establishes the Fluxus movement as inherently concerned with deconstruction, placing it on the trajectory of ‘negation art’ championed by DADA some decades prior. But to define Fluxus as, at base, antagonistic and destructive, is wrong. Fluxus artists were playful and collaborative. Thus, idealistically, the increasingly tight elitist grip on art would loosen. Emancipation and reclamation through assembly and play was the goal. An art for the people.

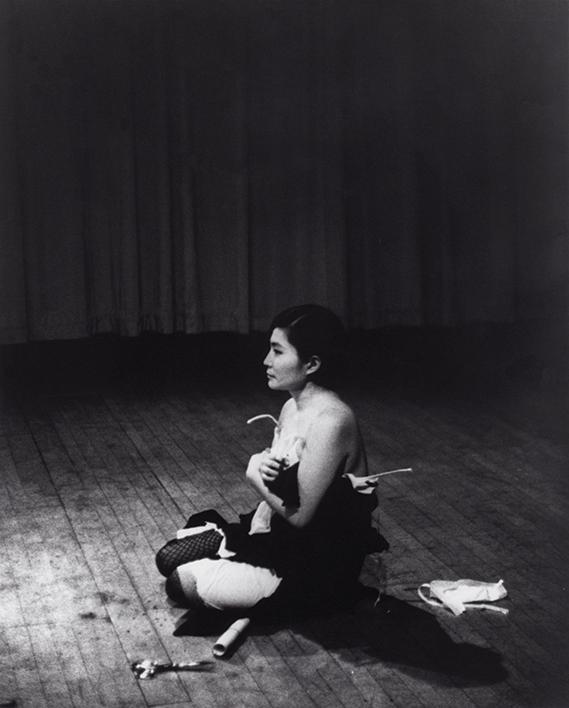

Perhaps one of the most playful artists associated with Fluxus is Yoko Ono. In 1960-61, Ono began work on her ‘Conceptual Instructional’ pieces. Her conceptual approach to art-making is indelibly inked onto the landscape of visual art. For Ono, “the instruction brings the concept of time into painting […] and breaks with the excessive solemnity of an original.” The reciprocity that these early works expose and celebrate is not to be underestimated. Whilst her practice was rooted in the conceptually abstract, she still considered herself first and foremost a visual artist. The MAC Lyon exhibition features several pieces from this early period, including the work Lighting Piece, 1955.

Though she never accepted Maciunas’ official invitation to join the Fluxus movement, Yoko Ono was integral to its maturation and remains key to its longevity. In the early years Ono and Maciunas collaborated sporadically, staging events and exhibitions of art, performance and music. Maciunas’ manifestos should by no means be taken as authoritative, but what he did do was cohesively vocalise a strong trend in artistic thought, one that encompassed the work of many of his colleagues and compatriots at the time. It is arguably in the spirit of these artists and works, particularly Ono, that Fluxus finds its lasting legacy.

Lumiere de l’Aube uses light as a guiding theme and as such, encompasses a large number of works from Ono’s early conceptual pieces, through to her more recent large-scale installation works. This comprehensive retrospective pays tribute to an artist who now, even as she enters her 9th decade, is still continually redefining herself as an artist.

Until 10 July 2016 mac-lyon.com

SARAH BOLWELL