The Ottoman empire (1299-1923) was once considered one of the most important economic and cultural powers in the world. It ruled over a vast swath of the globe stretching from the Middle East and North Africa to Budapest in Hungary in the north. Throughout the 15th and 16th centuries, the Venetian and Ottoman empires were trading partners – a mutually beneficial relationship providing each with access to key ports and desirable goods for trade.

Although various wars intermittently interrupted their relationship, both empires relied on trade for their economic well-being. The Ottomans sold wheat, spices, raw silk, cotton, and ash (for glass making) to the Venetians, while Venice provided the Ottomans with finished goods such as soap, paper, and luxurious textiles, along with other goods traded along the Silk Roads. The same ships that transported these everyday goods and raw materials also carried luxury objects such as carpets, inlaid metalwork, illustrated manuscripts, and glass. Wealthy Ottomans and Venetians alike collected the exotic goods of their trading partner, and the art of their empires came to influence one another.

The Frist Art Museum is presenting an exhibition to explore this specific relationship – Venice and the Ottoman Empire, by looking at the artistic and cultural exchange between the Republic of Venice and the Ottoman Empire over four centuries. This cross-cultural exhibition examines the complex links between the Republic of Venice and the Ottoman Empire from 1400 to 1800 in artistic, culinary, diplomatic, economic, political, and technological spheres. ‘The relationship between Venice and the Ottomans represents a fascinating and multifaceted chapter in the history of Mediterranean geopolitics, one marked by a blend of cooperation and conflict, handshake and arms-length approaches, diplomacy and back-stabbing, understanding and misunderstanding,’ writes exhibition curator Stefano Carboni in the exhibition catalogue.

Featuring a diverse selection of more than 150 works of art in a broad range of media, including ceramics, glass, metalwork, paintings, prints, and textiles, the exhibition draws from the collections of seven of Venice’s renowned museums. The paintings of well-known Venetian artists such as Gentile Bellini, Vittore Carpaccio, and Cesare Vecellio are showcased alongside works created by the best anonymous crafts people both in Venice and the Ottoman empire. The Venetian loans are joined by a selection of recently salvaged objects from a major 16th-century Adriatic shipwreck of a large Venetian merchant vessel that have never been exhibited outside Croatia. They come from the Gagliana Grossa, a fully loaded Venetian ship that sank in 1583 in the waters off the Dalmatian coast while travelling to Constantinople (now Istanbul).

Featuring a diverse selection of more than 150 works of art in a broad range of media, including ceramics, glass, metalwork, paintings, prints, and textiles, the exhibition draws from the collections of seven of Venice’s renowned museums. The paintings of well-known Venetian artists such as Gentile Bellini, Vittore Carpaccio, and Cesare Vecellio are showcased alongside works created by the best anonymous crafts people both in Venice and the Ottoman Empire. The Venetian loans are joined by a selection of recently salvaged objects from a major 16th-century Adriatic shipwreck of a large Venetian merchant vessel that have never been exhibited outside Croatia. They come from the Gagliana Grossa, a fully loaded Venetian ship that sank in 1583 in the waters off the Dalmatian coast while travelling to Constantinople (now Istanbul).

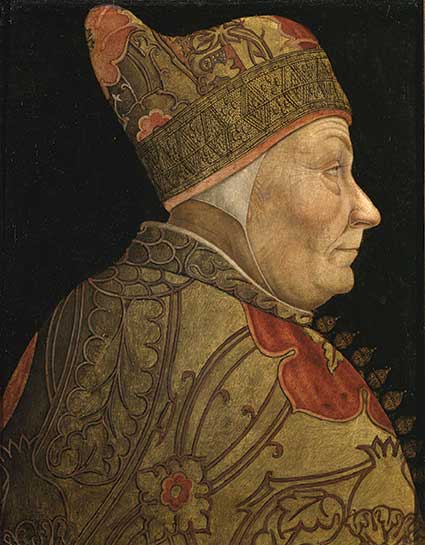

Organised thematically, the exhibition begins with an overview of diplomacy and trade during the period illustrated through portraits of powerful Venetian and Ottoman leaders including doges, sultans, and ambassadors. On display are nautical maps as well as a printed manual that illustrates how merchants who spoke different languages conducted business using hand gestures. Despite diplomatic efforts, relations were not always harmonious. Between 1400 and 1800, the two powers fought seven major wars, with the Venetians gradually losing almost all their overseas territories to the Ottomans.

The exhibition, however, emphasises that during periods of peace, the two powers forged a close relationship and shared aesthetic tastes. The museum’s curator-at-large, Trinita Kennedy, writes, ‘Venetians and Ottomans admired and sought one another’s luxury goods and gave them to each other as gifts. Ottoman sultans liked Murano glass and portraits of themselves by Venetian artists, while Venetian women wore Ottoman clogs and perfumed their homes with incense burners imported from Ottoman regions’.

The next two sections are dedicated to decorative arts and textiles, which figured prominently in commercial exchanges and the interior design of Venetian homes. Turkey and Safavid Iran (which produced and loomed raw silk) had for centuries been part of the trade networks linking Asia to Europe by land and sea. The Ottoman trade silks primarily came from the city of Bursa, the main entrepôt for the trans-shipment of raw silk from Iran to the west. By the early 15th century, Constantinople had also developed a silk-weaving industry, and by the end of the 15th century, velvet (kadife) had come to be considered the pre-eminent luxury textile of the Ottoman court, with a velvet-weaving industry established in Bursa, partly in reaction to the international popularity of the silk velvets the Italians produced in Venice and Florence.

Marika Sardar in the book Interwoven Globe comments, ‘Soon the technical accomplishments of the Ottoman weavers reached great heights, with the production of complex designs with contrasting areas of raised and voided pile as well as brocading with metal-wrapped thread (kemha and seraser), making Ottoman velvet the main luxury textile traded abroad. A distinctively Ottoman decorative style emerged from the court workshops based in the Topkapi Palace in Istanbul.

The design of the textiles evolved alongside that of ceramics, tiles, carpets, and even drawing, as all these media took up the same repertoire of motifs and arrangements. By the mid-16th century, popular motifs included pomegranates, artichokes, and tulips, often set along undulating vines, placed in ogival lattices, or used to fill other motifs such as medallions. Other popular motifs included tulips and carnations, the cintemani design (a pattern of three circles in a triangular pattern), and symbolic ‘tiger stripes’. Both cultures favoured red and gold, and bold designs with their textiles are so similar that sometimes it can be difficult to discern whether a textile was made in Venice or Bursa.

The next section is dedicated to the spice trade tracing how Venetian merchants traded through the Ottoman-controlled ports in Africa and Asia. Once spices arrived in Venice, they were unloaded for distribution across Europe. Some were resold directly to merchants arriving from the north, others were shipped on barges up the Po Valley and then transported across the Alps to Germany and France. The sea route sent spices to London and Bruges and on to Paris. In 15th-century Venice, saffron ranked as the most expensively trade spice with cinnamon, cloves, and nutmeg ranking next with pepper, although still a high price ranking below the other spices. The spice trade started to decline by the early 16th century the Venetians had lost their stranglehold, as the Portuguese and Spanish explorers found direct sea routes to Asia with the Dutch and British on their heels, who were hunting for their own spices wanting to further develop their own maritime trade routes in Southeast and subcontinental Asia.

In addition to spices, Venetians depended on trade with the Ottomans for coffee, figs, pistachios, raisins, salted sturgeon, sugar, vinegar, and, most importantly, wheat. This part of the exhibition leads to an exploration of ship building, sailing, and a storied shipwreck in the next two sections. One of the highlights here is a large group of objects recovered from the Gagliana Grossa shipwreck, illustrating the opportunities and perils of seafaring in this age. The ship’s diverse cargo offers evidence of the types of goods Venetians traded in the Eastern Mediterranean. ‘The Venetian Senate sent a Greek diver to salvage diamonds, emeralds, pearls, and some luxury textiles on board, but the rest of the goods remained on the seabed until the site was rediscovered in the 1960s,’ explains Kennedy. ‘Excavations are ongoing, and this exhibition presents some of the most recently found objects’.

Works in the penultimate section centre around the revered Venetian naval commander and doge Francesco Morosini (1619-1694), who played a major role in Venice’s interactions with the Ottoman Empire in the 17th century and amassed a large collection of art taken from his campaigns, as well as acquired from the Venetian art market.

The exhibition concludes with the return to textiles in a gallery devoted to the extraordinary creations of Mariano Fortuny (1871-1949), the Spanish artist, designer, and inventor who lived and worked for most of his life in a Gothic palace in Venice, creating sumptuous textiles with new printing techniques that recalled the Republic of Venice and the Ottoman empire.

Until 1 September, The Frist Art Museum, Nashville, fristmuseum.org. Catalogue available, Venice and the Ottoman Empire: A Tale of Art, Culture, and Exchange.