Social intercourse to change from a single individual to a group is universal. People come together for a multitude of reasons of creating a relationship, almost always of a mutually beneficial nature. There are end-purposes in almost all human endeavours, be they military, finance, science, the arts, or simply for the pleasure of another’s company. These themes can be seen in this exhibition, in New York, of traditional Chinese painting.

‘Alone’ as a Source of Inspiration

Harry Nilsson, in his Three Dog Night song, ‘One is the Loneliest Number That You’ll Ever Do’, merged two words, ‘loneliest’ and ‘you’ into an underlying message: being by oneself is social abandonment. This is an almost universal perception in euro-centric thought because humans are social animals, and it is not all that common in Western perception to consider one’s being ‘alone’ as a source of inspiration. Yet anyone involved with any creative activity may well disagree.

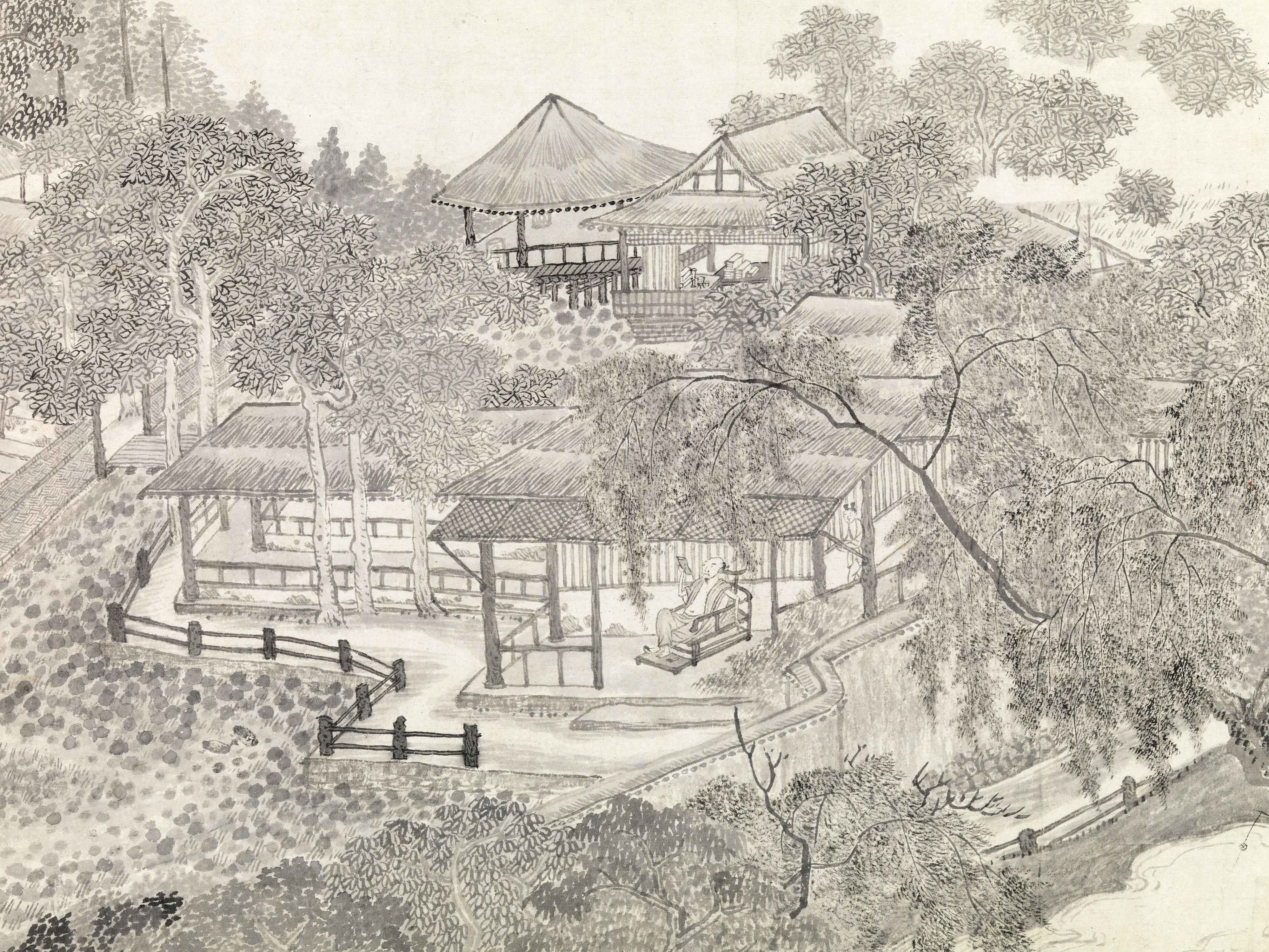

This subject-specific exhibition at the Met, which focuses on traditional Chinese painting, gives folly to that particular meaning of ‘alone’. Yes, solitude is defined as the state of living or being alone, but it does not infer social estrangement, and this comprehensive, two-part exhibition revels in the joy of solitude – singly or together. The paintings here do not include the old image of a lone figure in a cave – as that is intentional isolation. The exhibition dwells less on the single than the collective strength of a group. The most outstanding example of solitude and togetherness is the concept of and the compositions of scholars in a grove and depictions like the Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove, or people gathered together in a garden or landscape. Paintings of a lone fisherman framed by water and subsumed by two of the ‘Five Elements’ – water and stone, are frequent here. Fishermen perfectly represent both the active and physical aspects of human pursuits that can also take place during solitude. If anything, solitude need not static.

Most are works on paper, but there are some depicted on porcelain, mainly as round or carved wooden brushpots and porcelain censers, such as the Transitional-period incense burner with the Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove.

Oldest Traditional Chinese Painting in the Exhibition

The oldest painting by an identifiable artist is Summer Retreat in the Eastern Grove by Wen Zhengming (1470-1519.) He was obviously influenced by Ni San (1301-1374); the master of the stark landscape of a lake with several small islands on which grow a few skeletal trees. Eastern Grove is a masterful and contemplative creation and sums up the solitude of this thought-provoking exhibition. Included in this inclusive exhibition are some forty-something paintings that range in date from the early Nanbokucho period (1332-1392) through to this century, with the majority being Ming.

Whether horizontal or vertical, few are in strong colours, but depend rather on the diverse gradations of black ink, sometimes with slight colour, perfectly in keeping with the sublime subject of solitude.

Landscapes in this exhibition of traditional Chinese painting make their presence known by their quantity as well as their quality. Those depicting mountain views with streams and/or waterfalls are in tune with the Daoist laws concerning the ‘Five Directions’. Although north is believed to be the zone of darkness and cold, water flows from northwest to southeast, it is considered to be of benefit. If one looks at a map of the Forbidden City, one sees a large stream flowing from the northwest corner of the city to the southeast, with its flow passing directly in from of the Hall of Supreme Harmony, the most imposing of all of the imperial halls.

All of the scrolls on display are by both well-known, as well as famous artists, but not all of them are paintings. There is also a wonderful group of their personal letters, now mounted as hanging scrolls. If one is unable to read these, regardless of the writing style, one is missing out on one of the hidden mental pleasures of the exhibition – the written characters themselves. Beginning at the top right and reading down and then on to the next column, one can almost play a game with one’s eyes. The game is to follow the path of the brush for each character and sense the points where the tip of the brush begins with a strong stroke and continues to twist, pause,

and turn.

This exercise gives one a sense of belonging, which is, after all, the theme of this traditional Chinese painting exhibition.

BY MARTIN BARNES LORBER

Until 6 January, 2022, Companions in Solitude: Reclusion and Communion in Chinese Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, metmuseum.org. Second rotation runs from 31 January to 14 August, 2022