THE JAMEEL PRIZE is awarded biennially for contemporary art and design inspired by Islamic tradition. The resulting exhibition of the fourth edition recently opened at the Pera Museum, Istanbul, where the Prize was awarded to a Pakistani artist, Ghulam Mohammad. Subsequently it will travel to worldwide destinations. The work of the 11 artists and designers who were shortlisted from hundreds of entries demonstrates that Islamic traditions have been reinterpreted in ways that are vividly relevant to today’s world. The Prize also promotes wider debate about the role of Islamic culture in a time of such turmoil in the region and beyond.

Tim Stanley, co-curator of the prize and responsible for developing it, as well as senior curator of the V&A’s Middle Eastern collection, told me in Istanbul: ‘What the prize shows over the course of the four editions is that all sorts of artists are able to draw on Islamic tradition in all sorts of ways, and one of them is moderate Islam’. This is not to say that socio-political concerns are not addressed by artists submitting work for the Jameel Prize, indeed, two of the finalists in this year’s Prize, both women, confront such issues directly.

CANAN’s practice is influenced by her position as one of the leading defenders of women’s rights in Turkey. Both of her submissions portrayed protests and resistance to police excesses. Lebanese artist and graphic designer Bahia Shehab presented a Plexiglass curtain titled A Thousand Times No. During the Egyptian uprising of 2011-13, she sprayed the word la – ‘No’ in Arabic in different forms on the walls of Cairo.

However, it is Ghulam Mohammad that has won the Jameel Prize this year with his exquisite multi-layered collages of paper cuttings of text from discarded books, so intense, so intricate and miniature in scale that one needs a magnifying glass to do it justice.

Born in Balochistan, a remote rural part of Pakistan, he is deeply concerned that his mother tongue, Jamot, will die out. ‘I am trying to explore the relationship between language and identity. We are not reading or writing Jamot, or other rural minority languages in our educational system, which is dominated by Urdu, our national language. Our identities are fractured when we cannot use our native tongue.’

When eventually he broke away from his agricultural village, where art was an unknown concept, miraculously he made it to Lahore, where he gained a scholarship to study art at Beaconsfield National University. He graduated just three years ago, and apart from a brief residency at Art Hub, Abu Dhabi, has never exhibited before outside Pakistan. At 27 years old, and at the beginning of his career, he said: ‘I am so glad this exhibition is a travelling show, so my work will be seen around the world’.

The scale of his work reflects his training in Mughal miniatures, but he breaks the conventions of this two-dimensional figurative medium by creating an abstract three-dimensional art form. Also inspired by calligraphy, he said, ‘I am making a new visual language’ – his collages give language sculptural form. He uses a minute cutter to extract each individual letter from fragile, very old books, placing them layer-by-layer onto hand-made wasli paper with a tiny brush. ‘It is a meditation,’ he said, ‘because I spend anything up to 10 hours on end doing this, each work taking two to three months.’ Sometimes the process is even more complex, the letters laid on gold or silver leaf on top of the wasli paper. ‘It needs patience. I have to be cool, relaxed and breathe.’

The prize is a joint enterprise between the Saudi philanthropic organisation Art Jameel and the V&A, and there is history behind such collaboration. In the 1850s, the V&A started collecting Islamic art, the first institution in the world to do so, and unexpected in the heyday of the British Empire. It was part of a mission to reform the somewhat moribund state of British industrial design. The founders of the museum considered Islamic art and design superior to most Western production, amassing a huge collection with the original aim of guiding public taste and providing inspiring examples for manufacturers. It was believed that Islamic concepts about structuring patterns and matching decoration to shape and function could improve British design, as indeed they did.

In the extensive and in-depth catalogue produced for the first time to accompany this prize, Venetia Porter, curator of the department of the Middle East at the British Museum, who worked with Tim Stanley to initiate the prize, describes how the partnership with the Jameel family came about. ‘However, magnificent the pieces on show in the Islamic gallery may have been, the setting could not do justice to them, as the gallery had grown somewhat shabby and needed updating. It was therefore excellent news when the V&A announced in 2003 that it had received a substantial donation from Mohammed Jameel for the redevelopment of this display. The result was the superb new Jameel Gallery of Islamic Art, which opened in 2006.’ A year later Porter again met with Tim Stanley, who had led the redevelopment of the gallery, to discuss a proposal from Mohammed Jameel to promote the work of contemporary practitioners who drew on the great traditions exemplified in the new Gallery. And so the V&A was invited to organise a biennial award, to be called the Jameel Prize, that would reward and promote excellence in this field.

The then director of the V&A, Martin Roth, described the real spirit of cooperation with the Jameel family and foundation. ‘It is a lot more than just sponsorship; it is a very profound inspiration, a perfect dialogue. It is money allied with the message, but money is only a part of it – we are partners, the V&A and the Jameel Foundation’. It costs a lot to fund the Prize every two years – around one million pounds.

The prize is certainly worth winning: £25,000 for the artist, the same figure as the Turner Prize, and in its own way, just as influential, because of its legacy. Each of the finalists deserves a solo show, and due to the publicity and the two-year touring aspect, their work receives global attention and exhibiting opportunities even if they are not the winner. One of the judges this year was Rose Issa, who has for the last 30 years been la doyenne promoting Arab and Iranian visual art and film. Issa is a gallerist, curator, author and publisher who commented: ‘I think by investing in the touring exhibition and catalogue, one cannot say any more that the art critics and historians are not informed that these artists exist. The gallery curators too are hungry to find artists that can bring money or prestige (or both). So there is a race among them to find these artists, whether via the Jameel Prize, the biennales, or documentaries. With all the publicity, publications and of course the touring exhibition which makes the art works accessible to a different public than the acknowledged Western art hubs, there is no excuse to ignore virtually unknown artists like Ghulam Mohammad’.

As Tim Stanley commented: ‘The last Prize opened at the V&A, receiving over 140,000 visitors, and the tour being such an important element, we try to vary the types of places we’re sending it to – everywhere from San Antonio to Singapore, Moscow to Morocco.’ The first tour took the 2009 exhibition to six locations in the Middle East and North Africa. Jameel Prize 2011 was seen in four venues in France, Spain and the US. Prize 3 toured to venues in the Russian federation, the UAE and Singapore. Martin Roth added: ‘Since the V&A launched the Jameel Prize in 2009, the international touring exhibition have been seen by over 172,000 visitors around the world.’ It attracts enormous visibility for the artists, as well as questioning stereotypes about the Islamic world, creating debate, and as Roth said: ‘We all know that Islamic themes are not well received everywhere. The Prize somehow bridges the world, in times that are not easy to bridge the world’. This is successful cultural diplomacy – the power of art.

Can one extrapolate that the Jameel Prize contributes to a global visual culture as part of its legacy? Gallerist and curator Rose Issa commented: ‘If galleries can sell works at high prices locally, and people can invest’ (as in London, still the centre of the international art market), ‘money talks. As long as an economy works, then the art scene works. Then globalisation takes place – the more cosmopolitan a place is, the more people have a right to defend their own aesthetics and reference their own culture, rather than other cultures. Of course, the art market is important, but apart from its economic value, it opens different doors, different visions as to how we see the world. When these artists shortlisted for the Jameel Prize are good’ (and from such an intensive selection process – they are good) ‘they open different doors, challenging us into a new way of seeing and thinking.

Another aspect of the Prize’s legacy and impact is the fact that many of the artists involved work with traditional media, such as ceramics, carpet-making, calligraphy, mosaic, inlaid marquetry and mother-of-pearl, tapestry and metalwork. This gives work to craftspeople whose skills are in danger of dying out, instead – sustaining and developing them. This is especially true in areas like Syria, Iraq and Iran, as well as other parts of the Arab world, such as Egypt and now Turkey, where tourism is clearly at a low ebb. In addition, the prize brings into focus contemporary design from the Islamic world in fields such as fashion, architecture, product and graphic design. This narrows the perceived (and dated) separation between ‘craft’ and ‘fine art,’ contributing to cultural and economic development in the countries concerned. Jameel Prize 3 in 2013 was won by a Turkish fashion label called Dice Kayek, whose submission Istanbul Contrast was the brainchild of two sisters who draw on Ottoman tradition for inspiration. Furthermore, there is a case to be made that the Prize actually promotes the development of contemporary art from the region and its presence on the global aesthetic stage.

When it comes to ‘labels’ the Jameel Prize is not an award for contemporary Islamic art. As Tim Stanley pointed out: ‘Many artists and designers whose work has a connection with Islamic tradition consider themselves secular or wish to define themselves through a national rather than a transnational religious identity.’ In fact few artists today want to be labelled at all. Rose Issa said that she is personally against using words associated with religion, like ‘Islamic’ to describe their art. ‘It is complicated because to define it as ‘Arab’ art is inaccurate – the Iranians and Turks do not want to be associated with that. And we have Jewish and Christian people living in the area.’ Tim Stanley rounds off the ‘label’ debate: ‘The Jameel Prize is not about contemporary Islamic art. Our nominees, short-listed artists and prize-winners create a mosaic. This year’s prize included two Turkish and one Iranian artists. The label is contemporary art and design inspired by Islamic tradition’.

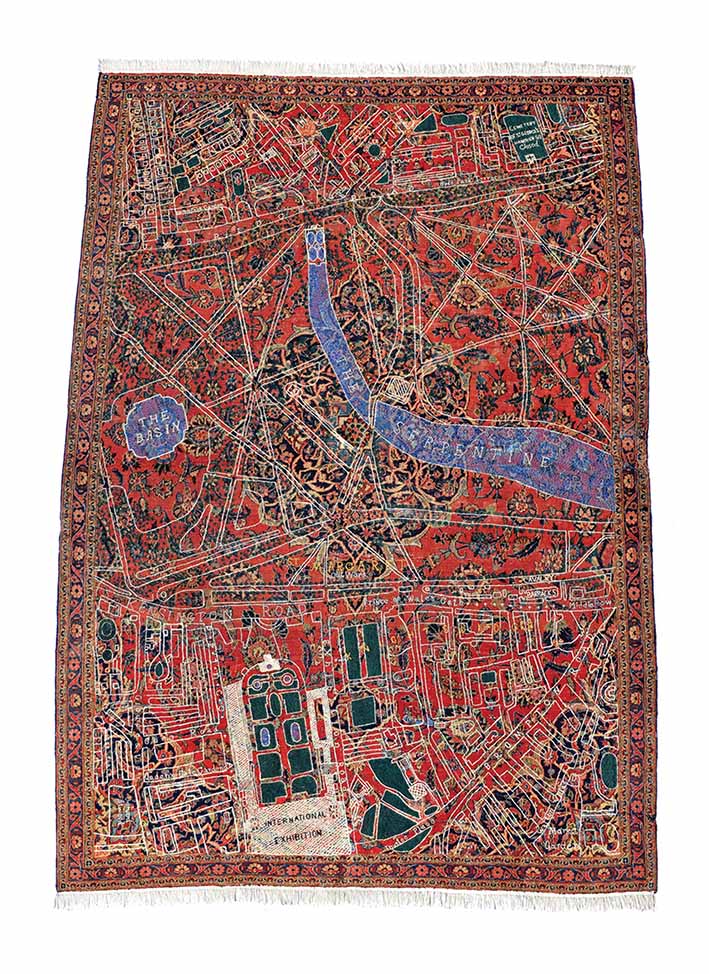

In fact, the Jameel Prize reaches out to new and different geographies in each edition. It has an international character, which includes people who are not from the Arab world at all, but draw on its culture. David Chalmers Aylesworth is British, but was completely immersed in Pakistani culture, living and working in Lahore and Karachi for more than 20 years. Now resident in the UK, over the last eight years he has produced a number of re-purposed carpet works. He re-embroiders carpets of Iranian and Pakistani origin, using the garden as a key metaphor, probing the relationship of humanity with the natural world, as in his Hyde Park Kashan 1862.

Living and working in Brazil, Lucia Koch creates ‘architectural interventions’, as she describes them, with filters and screens by covering facades, skylights and windows with translucent materials and metal filters. For Prize 4 she submitted two glistening screens of sliding frames of steel and mirrored acrylic. The screens echo the latticed window coverings, which adorned Brazilian homes from the 16th century onwards, after Portuguese settlers had imported Islamic traditions such as mashrabiya screens permitting women to look out of windows without being seen. As Rose Issa added: ‘As one saw from the Brazilian artist, more and more people from different places are inspired by Islamic culture, which includes many factors including its geometries and its literature’.

The criteria for submission of work is equally as inclusive, except for the fact that it must have been produced during the last five years, and that it must contain a clear reference to the traditional concepts or practices of Islamic art and craft. But implicit from the original conception is that the Prize is open to nominations for artists and designers from anywhere in the world, with no prerequisite of religious or cultural identity, be they furniture or jewellery makers, sculptors or calligraphers. The shortlists of artists for each award reveals nominations from Norway to Kosovo, the US to Algeria, drawing in Saudi Arabia and India as well as many more countries along the path of the four editions.

In his Introduction to the catalogue, Tim Stanley wrote: ‘We rely on nominations to put forward artists and designers… The tour promotes the prize internationally, helping us to recruit nominators and giving potential participants an informed idea of what the Prize stands for’. Camilla Canellas and Ann Jones of ArtsProjects & Solutions, who have been involved since the inception with the prize, explain in the catalogue how they have built and are still building ‘a network of potential nominators known and respected for their knowledge and insight – curators, critics, writers, academics, artists, designers, museum and gallery directors and other cultural professionals… As the prize developed, so did our global network’.

Then comes the selection process. Canellas and Jones continued: ‘Once the registration process has been completed, we work with the curators from the V&A… to prepare the long list that goes to the judges,’ (who change for each edition). It is their task ‘to measure each artist and designer’s submission against the criteria and to choose the names of the finalists. Their work is then included in the exhibition from which the winner is chosen’.

This year, for Jameel Prize 4 the judging panel included Alan Caiger-Smith, a potter world-renowned for his lustreware and tin-glazed earthenware, inspired by Middle Eastern ceramic traditions. He was joined by the Turkish sisters Ece and Ayse Ege, winners of the last Prize with designs for their fashion label Dice Kayek. Rose Issa was the third judge. Hammad Nasar formerly ran a non-profit organisation called Green Cardamom in London, whose gallery showed cutting-edge contemporary Middle Eastern art. He is now Head of Research & Programmes at Asia Art Archive, Hong Kong.

That is the process; what is the message? Of Lebanese-Iranian heritage, Rose Issa said: ‘We live in sad times for the Muslim world, and bad times for the region, where the image of Islamic culture is represented by totally ignorant, uneducated, mad men. But in Arabic jameel means ‘beauty’. The Jameel Prize is a prize for beauty. There’s love in it too – love of our history, love of our culture, all the time and concentration the artists give to creating their work. They produce intelligent art that expands the mind of the viewer, making some realisation click. This is how we advance in the world, by developing intellectually, morally and spiritually’. The power of art?

BY JULIET HIGHET

Jameel Prize 4 catalogue is published by Pera Müzesi, Istanbul, ISSN 9 786054 642595