To celebrate the 60th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations between China and France, as well as the China-France Year of Cultural Tourism, the Hong Kong Palace Museum is showing The Forbidden City and The Palace of Versailles: China-France Cultural Encounters in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries.

The exhibition presents nearly 150 treasures from both palaces, highlighting the rich history of diplomatic, cultural, and scientific exchange between the Forbidden City and Versailles during the latter half of the 17th century and throughout the 18th century. Nearly 150 objects are on show, including nine first-grade national treasures from China, sitting alongside important collections from Versailles.

The exhibition, divided into four sections, explores the key figures of the age, the palaces, and the cultural dynamics, scientific and diplomatic exchanges, craftsmanship and innovation in this age of discovery between the Chinese and French courts. Featuring nearly 150 treasures from the Palace Museum and the Palace of Versailles, it marks the first time artefacts from the two palaces are seen together in Hong Kong. Among the exhibits on show are objects from the main collections from the Palace of Versailles, as well as recent acquisitions, plus loans from local museums including the Hong Kong Maritime Museum and The Chinese University of Hong Kong Library.

The exhibition brings together these objects to form an overview of this cultural exchange during the 17th and 18th century, including large imperial and royal portraits, porcelains, glass, enamelwares, and textiles. Scientific exchange is represented through books, scientific instruments, and medical items, all highlighting the little-known stories of the two courts.

The Golden Age of the Chinese and French Courts

The 17th and 18th centuries are historically regarded as the golden age for both the Chinese and French courts. During the Kangxi (r 1662-1722), Yongzheng (r 1723-35), and Qianlong (r 1736-95) periods, the Qing dynasty experienced extraordinary economic and cultural prosperity, which opened new opportunities for foreign contact and trade. France had also adopted a more structured approach to its expansion in Asia during the 17th century, during the rule of Louis XIV. There was an organised attempt by the French to establish a strong trading empire by planning to take a share of the lucrative East India trade, and to counterbalance the trading power of other European nations. The first French East India Company was established in 1644.

During Louis XIV’s reign (r 1643-1715), the power and reach of the French Bourbon dynasty grew to unprecedented heights. Despite the vast geographical distance between the two imperial palaces, the diverse cultural differences, and the fact that the rulers of the two nations never met, the two powerful courts held immense curiosity for each other.

In 1685, to gain further ground in the East, the French king sent five Jesuit ‘mathematicians’ to China partly as a scientific expedition, but also with the aim of winning souls and spreading Christian beliefs in China, at the same time, counteracting Portuguese activity in the region. The French mission finally reached Beijing in 1688. After the first Jesuit missionaries arrived and became established, many other French Jesuits were sent to serve in the Qing court for extended periods of time. Their presence significantly influenced the Qing court in areas such as science, art, architecture, medicine, and cartography.

Sino-French Exchange

These Sino-French exchanges stand as testament to the profound mutual respect and appreciation that characterise the relationship shared by these two nations. An Edict of Toleration issued by the Kangxi emperor in 1692 showed the Qing court’s appreciation of the Jesuits’ scientific and technological contributions. However, this tolerance was not to last long, as by the first quarter of the 18th century, the Jesuits were confined to scholarly tasks producing historical works and translating Chinese classics, while many priests were banished to Macau. In 1717, decrees were issued which effectively banned the activities of Catholic missionaries, although the Kangxi emperor left enforcing them to his successor, Yongzheng.

The second Siamese Embassy to France in 1686 had also acted as a stimulus to gain further knowledge about the ‘Orient’. The mission brought thousands of Chinese ceramics to Louis XIV’s court, which further added to the demand for luxury products from the East among the court and nobility. A highlight of the exhibition is a silver jug, circa 1680, recently acquired by the Palace of Versailles. The jug was made in Canton (Guangdong) for the overseas market and was presented as a gift to Louis XIV by the Siamese envoy.

Chinese Porcelain

Chinese porcelain is also a focus of the exhibition. France was one of the first European countries to produce soft-paste porcelain, especially frit porcelain (faience), at the Rouen factory in 1673, developed in an effort to imitate the expensive Chinese hard-paste porcelains that were beginning to be imported in greater numbers to the country. There was a frenetic quest to discover the secret of manufacturing hard-paste kaolin porcelain. France, however, only discovered the technique of Chinese porcelain manufacture during the mid-18th century through the efforts of the Jesuit Francois Xavier d’Entrecolles (1664-1741), who had visited the kilns of Jingdezhen. His findings were first published in France in 1712 and republished in 1735 in The Letters of Père d’Entrecolles.

The luxury objects in the Forbidden City and Versailles exhibition emphasise the relationship between the two courts and illustrate France’s wish during this period for diplomacy alongside their desire to further develop their knowledge of Asia. Louis XIV’s diplomatic policy vis-à-vis his contemporary in China, Kangxi, was based on mutual trust and esteem, which is now often forgotten, but this collaboration and the links with their successors lasted until the end of the 18th century. This contact helped promote scientific studies and contributed to the birth of modern sinological studies in France.

As the French court developed a deep interest in Chinese culture and art, the demand for Chinese objects, such as porcelain, silks, and lacquer goods, grew not only at court but also in the domestic market in general. Trade between the two countries prospered, as Louis XIV championed the trend for Chinese blue and white porcelain, which was popular in the European courts at the time. The king even constructed a ‘Porcelain Palace’ in the garden of the Palace of Versailles. Marie Leszczyńska, the queen of Louis XV (r 1715-74), was also fond of Chinese art and transformed her private suite into the ‘Chinese Chamber’.

The attraction to China and Chinese art at the French court was manifested in various ways. The most obvious, as mentioned, is the importation of luxury Chinese objects into France. These Chinese trade goods were also imitated and, in turn, influenced French luxury goods created for the local market, as craftsmen formed new styles, such as ‘Chinoiserie’ to supply a growing demand for exotic items. Imported Chinese works were also transformed with additions in the French taste, notably with the use of gilded-bronze mounts for Chinese porcelains and the use of lacquer panels in French furniture and cabinets.

Chinese Influences on French Art

This cultural exchange produced a strong Chinese influence on national French art, particularly in the decorative arts field. The exhibition shows how Chinese art became an inexhaustible source of inspiration for French artists in fields ranging from painting, the making of objets d’art, and from interior and garden design to architecture. Other arts during this period also came under the influence of China, such as in literature, music, and science.

This influence remained strong and continued with other monarchs – Louis XVI and his queen, Marie Antoinette, also shared a passion for China. For example, Louis XVI commissioned a porcelain plaque of the Qianlong emperor’s portrait from the Sèvres factory to display in his study room at Versailles. The influx of Chinese crafts and literature into the French court that nurtured this new artistic style inspired by the French taste for Chinese items was naturally centred around the Palace of Versailles.

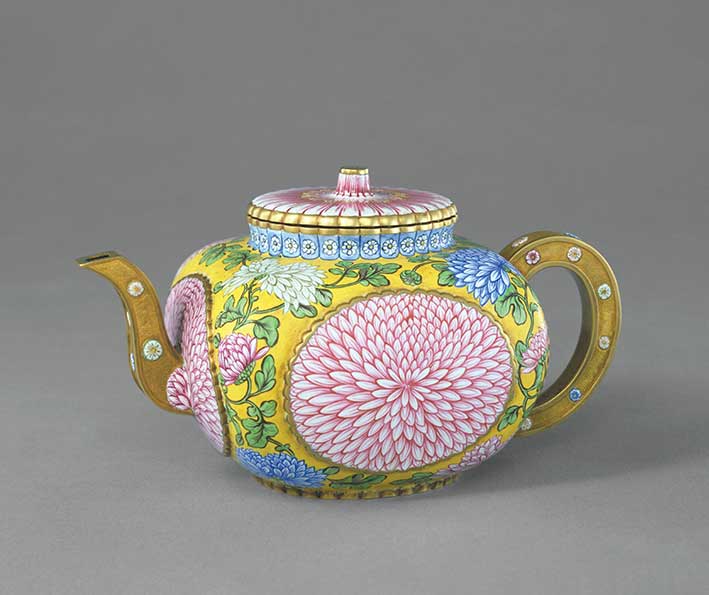

Another highlighted object in the Forbidden City and the Palace of Versailles exhibition is the chrysanthemum pot (1783) from the Palace Museum. Initially believed to be an enamelware for Qianlong’s court made in Canton due to its distinctly Chinese design, a recent examination revealed a signature ‘Coteau’ on the bottom of the pot, indicating that it was crafted by the renowned French enameller, Joseph Coteau (1740-1812), who also worked for some time at the Sèvres factory. This latest discovery uncovers an intriguing chapter in the exchange of artistic craftsmanship between China and France. It illustrates the fact that China and France not only imported and collected each other’s treasures, but their artisans also engaged in mutual learning and aesthetic exchange for over 300 years. This cross-cultural dialogue sparked new ideas, fostered innovative artistic forms, and advanced the development of craftsmanship in both nations.

To emphasise this point, a multimedia installation recreates a handwritten letter from Louis XIV to the Kangxi emperor in 1688. Written in Old French, the letter praises the Kangxi emperor and expresses Louis XIV’s desire to send Jesuit missionaries and introduce him to advancements in astronomy. At the end of the letter, it is signed affectionately: ‘Your most Dear, and Good Friend, Louis’. Although the letter never reached the Kangxi emperor, the Jesuit missionaries dispatched by Louis XIV had arrived in China at that time, which signifies the official beginning of many subsequent exchanges between the courts of China and France.

Uncovering the influences of the Sino-French exchange of the 17th and 18th centuries, the exhibition allows the visitor to explore the narratives of cultural interchange, mutual enlightenment, and innovation between the two courts.

The museum is also planning to host a scholarly workshop in the second quarter of this year to discover the latest research surrounding the Sino-French cultural exchange of that era.

The Forbidden City and the Palace of Versailles, until 4 May, 2025, Hong Kong Palace Museum, Hong Kong, hkpm.org.hk