Surimono are a distinctive form of Japanese colour woodblock prints that emerged between the late 18th and mid-19th centuries. Surimono literally translates to ‘printed things’ or ‘something rubbed’ (referring to the way a Japanese print is made by rubbing paper laid onto a woodblock line-engraving). However, these prints hold far more meaning than their technical creation. In this exhibition, Japan de luxe – The Art of the Surimono Prints, the genre is explored in over 100 prints, most of which are gifts of Gisela Müller and Erich Gross to the Rietberg Museum and are on show for the first time.

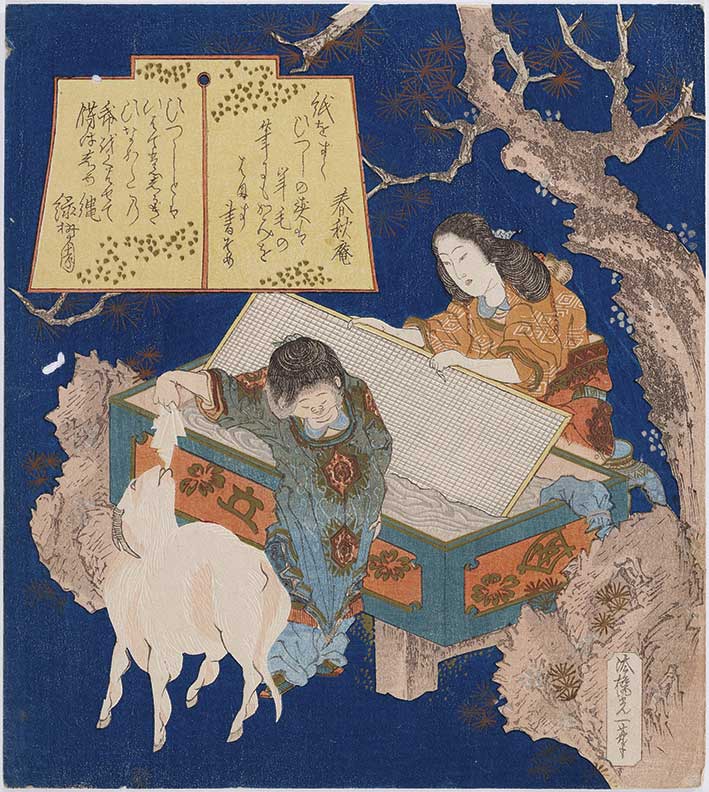

These luxurious greeting cards were made to mark seasonal festivals, personal and professional milestones, and special cultural events. Their often-exquisite design was made to delight both givers and recipients, as were the multifaceted literary and cultural references contained in the poems and visual motifs also printed on the card – the prints often combined images with selected calligraphy, most often in the form of poems. Prints with poems were popular commissions for New Year, often privately published and usually commissioned by a poet or a poetry club. These prints are full of clever hidden meanings, in allusions both in the poetry itself, and linked to the poem and the image portrayed. Poetry was an integral part of everyday life in Edo, common in all social classes ranging from samurai to courtesans, with poems written for personal taste or for special occasions. The growth of Edo and the rise of the nouveau-riche merchants had made an opportunity for artists and publishers to flourish. Ukiyo-e and surimono became the focus and drive of a new and vibrant culture emerging in the rapidly changing city thirsty for entertainment.

Artfully designed and intricately printed on high-quality unsized hosho paper, surimono reflect this burgeoning middle-class culture of the Edo period. They became a symbol of luxury and achieved a special depth and structure to their form through embossing and blind printing techniques. They can be highly decorative and use striking colours and precious metallic powders, including gold and silver, to add to the overall opulent feel of the print – creating a symbol of the epitome of luxury.

Surimono were printed in small editions of 50 to 500, intended as intimate gifts commissioned by the urban bourgeoisie. They served as status symbols for the select group who commissioned them, reflecting the tastes and fashions of society at that time. Poets, painters, and printmakers required more than mere poetic and artistic talent to be successful, their work also demanded a comprehensive knowledge of literature and history in addition to a familiarity with classical references and traditions.

In Surimono: Poetry & Image in Japanese Prints, Charlotte van Rappard-Boom explains, ‘The technical aspects of making a surimono are the same as those for a commercial print, such as ukiyo-e, but the role of the publisher is taken over by the poet, the poetry club, or the patron who commissioned the print. These individuals or clubs paid the production costs and could specify the subject of the print.

Workshop surimono were sometimes produced without poems. A client could choose a fitting image for the zodiac year or any other special or personal subject-matter and have a poem added after the print run had been completed. Surimono designed for poetry clubs, or as special invitations, were also sometimes reissued commercially and these second editions were often printed with different poems, or the poems were omitted entirely. It was one way to recoup some of the considerable investment required to finance the original surimono, which could be printed using up to 10 blocks. Societies also used these prints to commemorate the results of poetry competitions. Therefore, they provide insights into the diversity of the literary scene at that time. Amateur poets in Kyoto and Osaka composed short haikai poems (known today as haiku). They would often be illustrated by painters of the famed Shijo school with light-hearted everyday scenes. In Edo, the 31-syllable satirical kyoka poem was more common, authored by well-known literary figures and illustrated with great attention to detail by acclaimed woodblock artists including Hokusai, Kunisada, and Kubo Shunman’.

Kabuki fans, on the other hand, used surimono to mark major performances and the birthdays of famous actors. These prints offered an effective means for stars, who were celebrated not only as gifted actors but also as fashion and beauty icons, to promote themselves to their fans and the public.

Kabuki was always a popular subject matter for these prints. An outing to the theatre usually took a whole day as plays were normally only performed during daylight hours. Theatre-goers could buy their tickets at one of the teahouses near the theatre and, if they could not afford a box, would site in the square partitions on the main floor of the theatre. The teahouse also supplied them with a programme and a mat to sit on, as well as providing them with tea, snacks, and lunchboxes.

Specific surimono were also commissioned when an actor from a well-known family changed their name. The majority of this type of surimono show kabuki actors in the most important scenes in the plays they performed, their most famous character roles, and famous poses, although the name of the play or the character portrayed are not recorded on the surimono. The Ichikawa family was probably the most famous acting dynasty of the Edo period, and their leading actors all took the name ‘Ichikawa Danjuro’. The patriarch of the family, Ichikawa Danjuro I (1660-1704), was born in the theatre district in Edo and made his debut at the age of 12 in the role of the strongman Sakata Kintaro. He is credited with the arrogoto (bravura) style of acting in which the swashbuckling hero or ruffian overpowers his enemies.

These prints were printed to reflect all seasons, yet most of the extant prints are New Year’s cards – a time when friendships were reaffirmed and neglected personal relationships rekindled. New Year surimono reveal which symbols were particularly popular at the turn of the year as well as what actions were considered auspicious. This was a time of spiritual renewal and rest, as well as taking care of practical affairs, like housecleaning and settling financial debts. Special activities and festivals connected with welcoming an auspicious beginning to the New Year occur over a period of several days. Exchanging surimono with friends at the poetry clubs would be just one of these seasonal activities. From today’s viewpoint, they also offer valuable insight into everyday life and the material culture of the urban bourgeoisie in Japan during the late 18th and early 19th centuries, as they often depicted household decorations, special food and drink that was prepared for the family and guests, and other seasonal customs.

Manzai (New Year’s) dancers, lion dances, and monkey trainers with their dancing monkeys are popular subject matter for surimono. The zodiac animals were favourites –monkeys especially so in the year of the monkey. A period of 60 years was considered a full life cycle in Japan as this is how long it took to complete the zodiac style combining the 12 animals with the five elements. Traditionally, you would begin counting anew after reaching the age of 60. The zodiac animal associated with the coming year was included in some way on calendar prints, with 12 objects chosen to represent the different length months sometimes being included in the design.

Surimono bring the social and cultural side of Edo society to life through the careful choice of their design, materials used, and poems and wishes presented on the cards. This exhibition allows the view, to glimpse that world through the themes used in these printed cards revealing the fashions, tastes, and trends of the time.

Until 12 July 2026, Rietberg Museum, Zurich, rietberg.ch

The exhibition is divided into two and the surimono exchanged for conservational purposes, from 26 Sept to 15 Feb 2026 and 19 Feb to 12 July 2026