Lying along the trade routes between India and China, the islands of Southeast Asia have been a crossroads for merchants, pilgrims, and travellers from many parts of the world. Weaving Stories, brings together more than 40 examples of Southeast Asian textiles and garments from across Indonesia, as well as the Philippines and Malaysia, to consider how fabrics produced primarily by women, such as the ikats and batiks that have inspired global fashion for centuries, are woven not only into the daily lives but the cultural foundations of these communities. At the same time, the exhibition shows how hand-made and naturally dyed textiles provide a platform for self-expression and social meaning for women, both as artistic innovators and as vital transmitters of scientific knowledge.

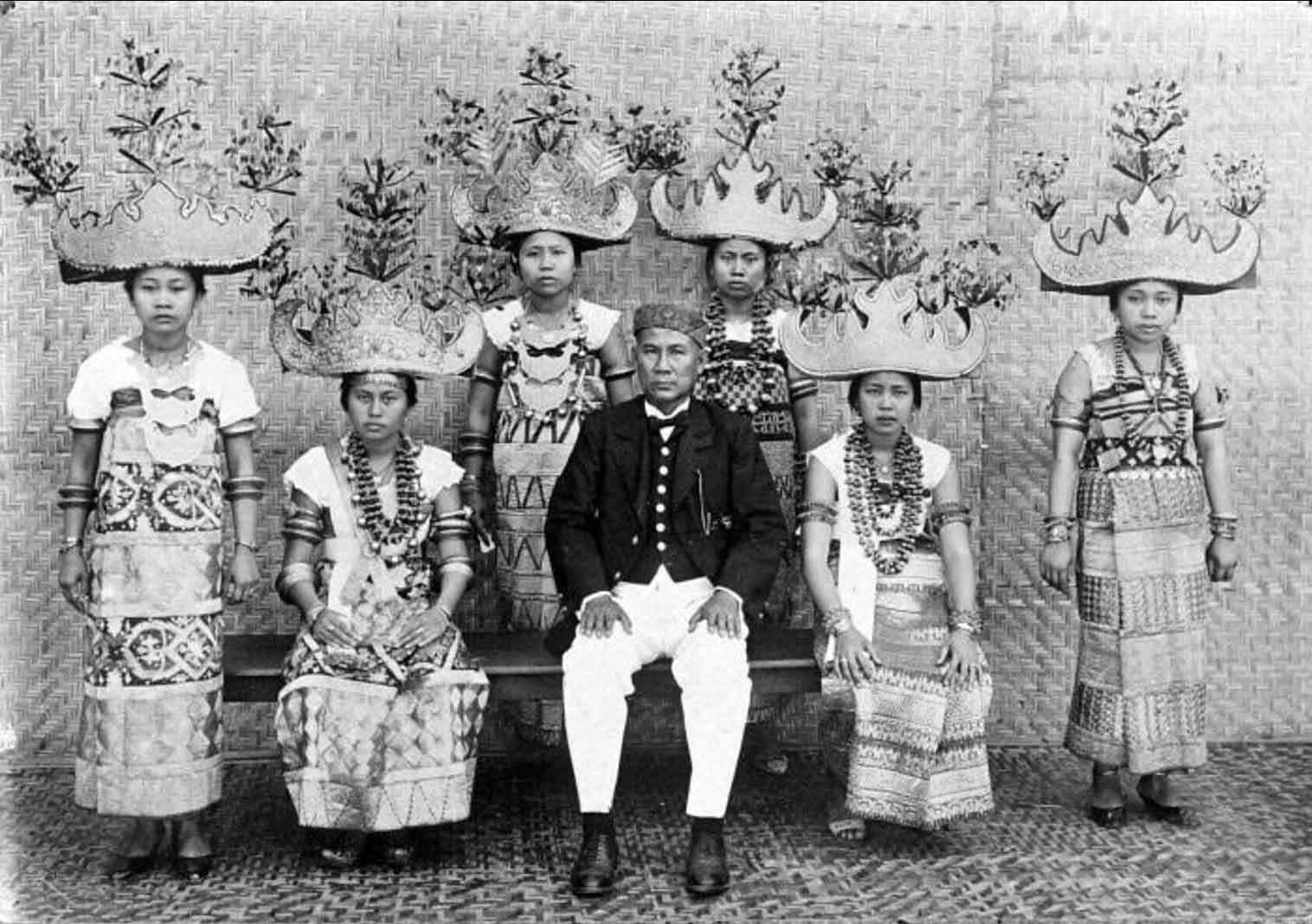

By featuring Southeast Asian textiles from the 19th and 20th centuries, in combination with archival photographs, the exhibition also forms a portrait of an ancient craft tradition that is equally able to reflect the complex communities and events of the modern world. One touching narrative garment on view is by artist Milla Sungkar depicting the devastation of the 2004 Aceh earthquake and tsunami, but many of the textiles in the exhibition also tell individual stories.

‘Reading Textiles’ in Southeast Asian Textiles

The clothing in the exhibition can be ‘read’ to learn the wearer’s age, gender, marital status, or ethnic identity. The elongated diamond shape in the centre of a chest cloth from Java, for example, showed that the wearer was a married woman. White batiks with dark blue patterning could indicate membership in the Indo-Chinese community and often signalled that the wearer was in mourning. Among indigenous peoples of the southern Philippines today, traditional garments like finely decorated blouses are markers of cultural identity, as well as symbols of resistance and resilience.

The ability to dye was as valued as woman’s ability to weave. Blue derived from the leaf of the indigo plant and red from the root of the morinda plant provide the basis of the colour palette for many traditional textiles. The Asian Art Museum has some of the earliest known examples of indigo cloths decorated with batik, as well as bold ceremonial textiles foregrounding red. Masterpieces like those on display would have needed dozens of immersions in a dye bath to achieve these saturated colours, and their enduring brilliance invites visitors to appreciate them as pure works of art and to consider how the complexity of their production increased the status of both their maker and their wearer.

Textiles and Faith

Textiles were used by people from every faith tradition across the region in their spiritual lives, often as talismans. A striking example is a rare silk ritual cloth (cepuk) from Bali; spiky white triangles along its borders symbolize the teeth of the guardian deity Barong, revealing the cepuk’s protective function. A deep red cloth ornamented with symbols of longevity and good fortune was used by Indonesians of Chinese heritage to drape a home altar to their ancestors. Among the Iban in Borneo, textiles ornamented with intricate ikat patterns were made to line the walls of longhouses and invited the support of gods and ancestors.

This exhibition of Southeast Asian textiles highlights the remarkable diversity of style, technique, and ornamentation of Southeast Asian textiles. With the sea connecting people as much as it divided them, sailors crisscrossed archipelagos bringing textiles with them. Those connections, as well as the introduction of Islam and Christianity, changed modes of dress in many ways; tailored jackets, pants, and Western clothing joined and sometimes supplanted older traditions of draped apparel. In most parts of the region today, mass produced textiles are worn in everyday life, but handmade textiles continue to be used in weddings, funerals, and other milestone or ceremonial events.

‘Textiles are expressions of self within social networks of family or ethnic groups; they are simultaneously very intimate and highly public,’ explained Natasha Reichle, Associate Curator of Southeast Asian Art. ‘This exhibition helps us think about textiles as both works of art and as markers of identity, belief, and standing within a broader community’.

Weaving Stories runs until 2 May, 2022, Asian Art Museum, San Francisco, asianart.org