The prints designed by Japanese artist Ito Shinsui (1898-1972) feature traditional subjects, bold colours, and realism that went beyond 19th-century norms, a combination that achieved remarkable commercial success. In his homeland his reputation rested upon his paintings (from his later years), but Shinsui’s technically accomplished prints were hugely popular overseas, which encouraged him to design works specifically for foreign audiences.

Ito Shinsui Was Born in Tokyo

Ito Shinsui was born in Tokyo to a relatively wealthy merchant family. When he was around nine years old, however, his father’s business failed, and Shinsui left school to work at a printing factory, where he was an assistant typographer and lithographer at the Fukagawa Workshop of the Tokyo Printing Company. In 1911, he entered the studio of Kaburagi Kiyotaka (1878-1972), who was trained in the tradition of the Utagawa School, known for their depictions of beautiful women and Kabuki actors.

Shinsui’s talent and self-discipline earned him a prize in the first exhibition he participated in – aged fourteen. His early works won many awards, including a prize at the Peace Memorial Tokyo Exposition. Shinsui also supplied illustrations to popular newspapers, such as Tokyo Nichi Nichi Shimbun (published from 1872 to 1943).

Ito Shinsui Established His Own Studio

In June 1915, one of his paintings was displayed in a shop and caught the eye of the successful publisher Watanabe Shozaburo (1885-1962), who asked Shinsui to collaborate on a print version. The result was Before the Mirror, first published in 1916 – the start of a long and fruitful collaboration. By 1927, Shinsui had established his own independent studio and although many of his early works were direct reflections of ukiyo-e in subject matter and in style, his technique was considered revolutionary at the time.

The artist’s rise in popularity was in tandem with the changes seen in the early 20th century society and the rise of two important art-print movements in Japan: shin-hanga (new prints) and sosaku-hanga (creative prints). Ito Shinsui was associated with the shin-hanga movement, which flourished during the Taisho (1912-1926) and Showa periods (1912-1989).

Time of Change

This was a time of change, as a watershed moment was created when the Meiji Emperor died and the Taisho Emperor succeeded to the throne. Shi-hanga strove to revitalise classical ukiyo-e of the 18th and early 19th centuries that had fallen out of popularity in the last decade with the onslaught of rapid industrialisation and Westernisation during the Meiji period (1868-1912), plus the arrival of new technology with the advent of photography.

This movement produced works that were labour intensive, as it utilised the classical collaborative (hanmoto) system, an almost assembly-line division of skills, where the creation of a print began with the artist’s drawn design, which was then passed on to the block carver, then to the printer and finally to the publisher/distributor for sale to the public.

Collaboration Between Watanable and Shinsui

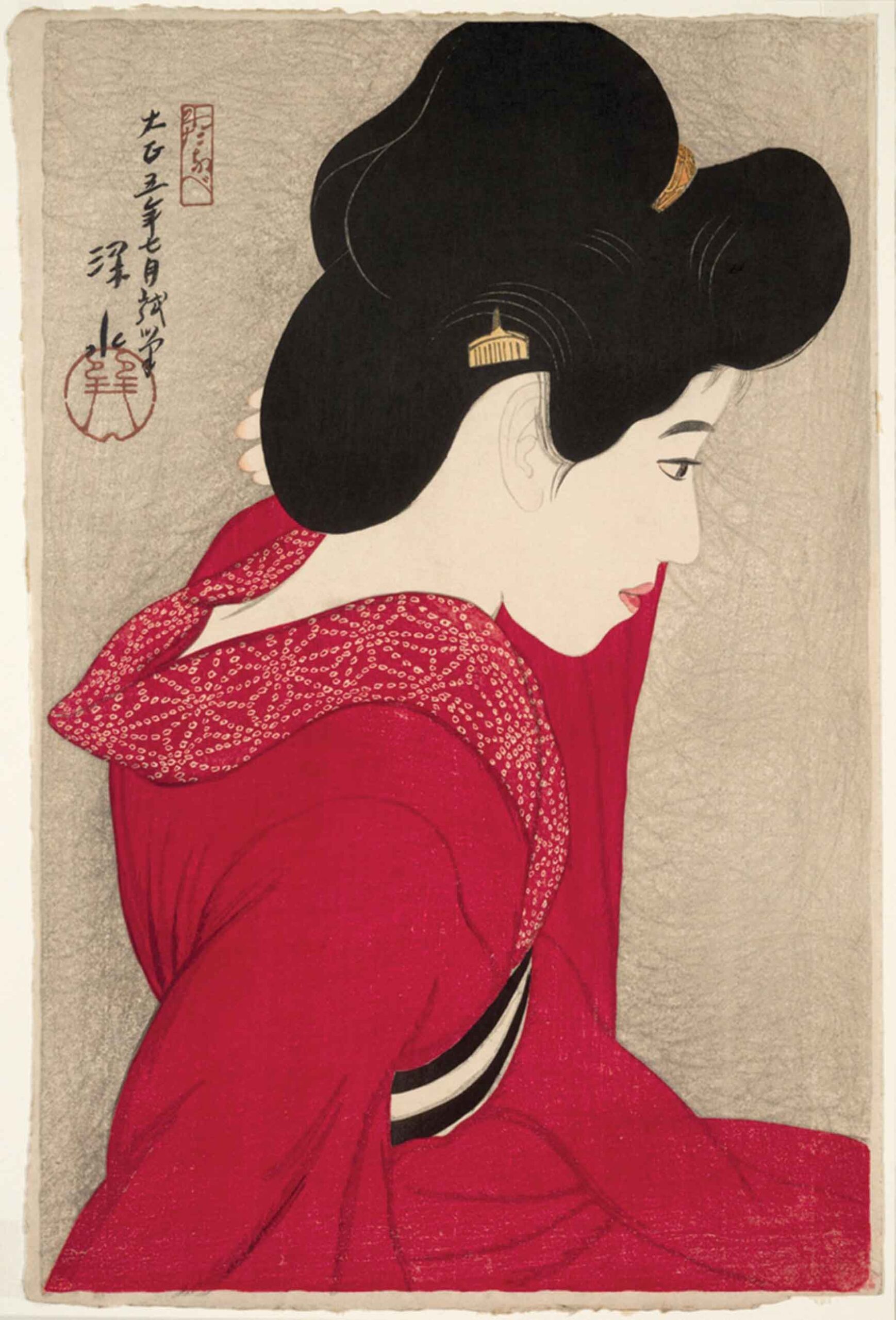

The collaboration between Shinsui and Watanabe continued until 1960, this productive partnership produced 63 bijin-ga (depictions of beautiful women) that are Shinsui’s most enduring legacy. They also produced several dozen landscapes. The earliest of these series, Omni Hakkei (Eight Views of Omi), is included in an exhibition of Shinsui’s work currently at the Art Institute of Chicago.

Ito Shinsui’s work with Watanabe confirmed his position as the most important artist in the shin-hanga movement, which helped ukiyo-e transform and survive into the 20th century . However, in later years, the artist worked mainly in aother style – as a celebrated Nihonga (Japanese-style paintings) artist. In 1933, Shinsui became a judge for the Teiten, the Shin-bunten, and the Nitten (Japanese Art Exhibition) and was honoured by membership of the Japan Art Academy.

From 1937, Shinsui began to take a new interest in landscape prints and created the series Oshima junikei, (Twelve Views of Oshima). A visit to China, in 1939, further stimulated this trend and, in 1943 during the Second World War, he published three Nanyo Sukecchi (Sketches from the South), after visiting the war zone as a Japanese Navy official war artist.

Ito Shinsui’s Prints Designated Intangible Cultural Property

The government, in 1952, recognised his mastery of woodblock design and his work designated as Intangible Cultural Property, an event that was commemorated with the print Tresses, and later in the decade he became a member of the Japan Art Academy.

As the 1950s advanced, Shinsui was creating more Nihonga paintings that included folding screens and albums, as well as hanging scrolls – he was equally at home on paper or silk, and for subject matter would often choose female subjects drawn from society or bourgeois life. He was highly skilled at portraying the modern world using Japanese artistic traditions, looking to the world of dance, geishas, or the theatre for subject matter.

The final accolade in his life was in 1970, two years before his death, when he received the Order of the Rising Sun, a decoration created by the Meiji Emperor in 1875 and given by the government to honour distinguished achievements by its citizens.

Ito Shinsui an Important Artist of the Shin-hanga Movement

As undoubtedly one of the most important artists of the shin-hanga movement, Ito Shinsui not only helped revive the art of the woodblock print, but also helped document the extraordinary changes taking place at the time in Japan, both in society and the artistic world.

The height of this movement was from around 1915 to 1942 and then briefly from 1946 through the 1950s. The shin-hanga artists’ inspiration not only came from Japanese subject matter, but also from European Impressionism with the frequent incorporation of foreign techniques of representing light and shadow that could explore the ‘mood’ of the subject – especially in landscapes.

The opening up of Japan during this period also saw the introduction of other Western influences in art that disrupted the representation of traditional subject matter as it was previously depicted in prints. However, as in the traditional ukiyo-e of the previous centuries, these modern artists, including such important new-thinking artists such as Hiroshi Yoshida (1876-1950) and Kawase Hasui (1883-1957), also still relied on the same traditional themes, just portrayed in a new way, in such traditional themes as landscapes (fukei-ga), famous places (meisho), beautiful women (bijin-ga), kabuki actors (yakusha-e), and birds-and-flowers (kacho-e).

Little Interest in Japan

In the early part of the Meiji period and into the early 20th century, there was little interest in the shin-hanga prints in Japan – the real market for this new style lay in the West, where both ukiyo-e and shin-hanga prints were considered fine art. This interest was mainly created by the publisher, Watanabe, who tirelessly produced English-language catalogues to market these prints and the artists he worked with to the West. It worked.

Interest in the West

Articles about the movement began to appear in English-language art magazines around the world, bolstering their popularity. Watanabe was acutely aware that their best market lay abroad, as these new prints portrayed the nostalgic and often romanticised views of Japan that were so prized and promoted in the West. Exhibitions were held in Tokyo (to attract tourists and foreign residents), and sent to international exhibitions of Japanese art, such as those held in 1930 and 1936, at the Toledo Museum of Art, Ohio, along with several exhibitions held in the UK and France. Accordingly, they became wildly popular from the 1920s and 1930s onwards in Europe and the US.

Ito Shinsui recognised that his prints needed to reflect this watershed period in Japan and needed to record the emergence of modernity in Japan – and to a greater extent the West. Shinsui also understood the commercial aspect of this process, as he saw the demand created by Watanable for his work. This changing world allowed shin-hanga artists to ride a wave of popularity, when their prints were sold all over the world. A popularity that continues to this day.

There is an exhibition of the prints of Ito Shinsui, until 13 June, 2021, at the Art Institute of Chicago, artic.edu