The inspiration for this major exhibition on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of the Cleveland Museum of Art was the December 2013 acquisition of works from the Catherine Glynn Benkaim and Ralph Benkaim Collection of Mughal and Deccan Paintings.

Made between the mid-1500s and mid-1700s, when the Mughals ruled India, the Benkaim Collection paintings have brought the museum’s holdings in this celebrated genre of Indian art to the level of comprehensive and world class. As a gift to all visitors during the centennial year, Art and Stories from Mughal India is free to all, as is admission to the museum itself. Also free to anyone anywhere is the innovative CMA Mughal exhibition app, in which the curator relates stories and describes paintings; the app includes hyperlinks to an illustrated audio glossary of names and terms and 100 short tweetable facts about the 100 Mughal and Deccan paintings on view.

The Persian Idea of Nama

This exhibition is organised on the basis of the Persian idea of the nama. Nama translates into a number of English words, among them: book, tales, adventures, story, account, life, and memoirs. Mughal painting got its start largely as an integral element of the production of namas in book form for royal collections in India.

Seven Persian painters who came from Iran to India in the 1550s had just previously contributed to the monumental and exquisite Shah-nama (Book of Kings) for Shah Tahmasp (r 1524-76) of Safavid Iran. Once Akbar (r 1556-1605) became the third Mughal emperor, he brought dozens of Indian artists from various regions to his atelier to work with the Persian court painters in the creation of a Tuti-nama (Tales of a Parrot) (fig 1), Hamza-nama (Adventures of Hamza), Babur-nama (Memoirs of Babur), Chingiz-nama (Book of Chingiz Khan) (fig 2), and many others.

This exhibition of Mughal and Deccan paintings sets the paintings, now long separated from their bound volumes, into their nama contexts. The show’s spaces are further enlivened with examples of architectural elements, garments, textiles, carpets, arms, armour, jewellery, and decorative arts that evoke the material culture of the Mughal court where the paintings and their stories were seen and heard. Joining objects rarely on view from Cleveland’s own collection are works generously lent by the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco, Brooklyn Museum, Harvard University Art Museums, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Mughals were Multi-Ethnic and Multicultural

As can be seen in the art, the Mughals themselves were inherently multi-ethnic and multicultural, and these characteristics were indispensable for their success in governing most of present-day India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Bangladesh. Babur (1483-1530), who founded the Mughal dynasty of India, was the eldest son of the ruling family of a principality in eastern Uzbekistan, called Ferghana, which was once part of the Chaghatai Khanate, a subdivision of the Central Asian lands conquered by Chingiz (Genghis) Khan (d 1227) in the 1200s and governed by his son Chaghatai Khan (d 1241).

In the centuries after Chingiz Khan, Mongols in Central Asia intermarried with indigenous Turkic groups. Babur was thus of mixed Mongol and Turkic descent, and he could trace his lineage to both Chingiz Khan and the 14th-century Turko-Mongol conqueror Timur (d 1405). Babur determined to finish what his ancestor Timur had started in the 1390s: the conquest of India.

In 1526, about 30 years after his departure from Ferghana, Babur defeated the Afghan sultan who had been controlling the regions surrounding Delhi and established what is known as the Mughal Empire, then stretching only from Kabul to Delhi. Babur was a bibliophile, and in his extensive memoirs, the Babur-nama, he refers to his copy of the Zafar-nama, a history of Timur, which often informed his decisions and military manoeuvres. Babur’s son Humayun ruled from 1530 to 1556, with a 15-year hiatus in exile spent partly at the Safavid court in Iran.

The Reconquest of India

Upon his reconquest of India in 1555, he brought to Mughal imperial identity a deep admiration for and emulation of Persian court culture, which included being thoroughly conversant in poetry and literature. By the end of his reign, his son Akbar had recruited more than 300 Indian artists who incorporated the exuberance and fervour of Indian painting into scenes of dramatic action that Akbar enjoyed.

He also welcomed international visitors to stay at his court, notably representatives from three Jesuit Catholic missions from Italy and Spain who had settled in the Portuguese port city of Goa on India’s western coast. They brought Flemish prints and Italian oil paintings as gifts to the Mughal emperor between 1580 and 1614. Mughal exposure to world art further expanded under Akbar’s son Jahangir and grandson Shah Jahan, since they also received mercantile and diplomatic emissaries bearing gifts from Portugal, the Netherlands, Britain, Tibet, and China.

Seeking to please their royal patrons, Mughal artists embraced what they considered to be the best aspects of all these different traditions and unified them into a coherent new style. Mughal painting is thus defined by its synthesis of multiple elements: Turko-Mongol dynastic ideals, Persian language and literature, the experience and training of Indian artists from diverse regional traditions, and selective appropriation of various international visual sources.

Imperial Resources Were Used to Buy Materials for Paintings

The results are dazzling. Imperial resources were poured into the acquisition of high-quality materials for making the paintings, including pigments made from gold, silver, lapis lazuli, and other costly ingredients. Artists whose work the emperor favoured received weekly rewards, and careful accountings recorded the value of illuminated books in the Mughal collections.

These books were housed in the treasury or the women’s quarters, with select volumes strapped to the backs of camels and taken on military campaigns. Women of the harem were encouraged to be multilingual and highly literate patrons themselves. The appreciation of art and literature was an essential component of life among the Mughal elite, both in a palace setting or wherever the emperor and his nobles travelled around the land. Books and storytellers travelled with them.

Exhibition Traces the Story of the Mughals in India

In eight sections, the exhibition of Mughal and Deccan paintings traces the story of the Mughals of India – like a ‘Mughal-nama’ – through 100 paintings drawn from the collection of the Cleveland Museum of Art. Four of the eight sections focus on a specific story: the Tales of a Parrot, Life of Christ, Story of the Persian Epic Hero Rustam, and Romance of Joseph the Prophet. Whenever possible the paintings are displayed double-sided to show complete folios from albums and manuscripts, a constant reminder of their original status as part of a larger book or series.

Mughal Paintings Made for Akbar

Sumptuously designed to evoke the spaces of Mughal palace interiors and verandahs where paintings were kept and viewed, the exhibition opens with a 25-foot-long 16th-century floral arabesque carpet, rarely seen because of its scale. The first two galleries are devoted to Mughal paintings made for Akbar, who saw to it that his copies of fables, adventures, and histories were accompanied by ample numbers of paintings.

On view are some of the earliest works by celebrated named artists, such as Basavana (Basawan) and Dasavanta (Daswanth), and the culminating scene from the Hamza-nama, 70 cm in height, one of few surviving pages from this massive 1,400-folio project in which the Mughal style became thoroughly synthesised.

Relationship Between Akbar and His Oldest Son Salim

The next two galleries of Mughal and Deccan paintings explore the relationship between Akbar and his oldest son, Salim, whose birth in 1569 was cause for great celebration. By 1600, Salim was ready to lead the empire and mutinously set up his own court where he brought paintings, artists, and manuscripts from Akbar’s palace and commissioned new works, such as the illustrated Mir’at al-quds (Mirror of Holiness), a biography of Jesus written in Persian by a Spanish Jesuit priest at the Mughal court, completed in 1602 (fig 3).

Like the Tuti-nama, the Mir’at al-quds manuscript is remarkable not only for its historical importance and artistic beauty, but because it survives nearly intact, though unbound, with few missing pages. Both manuscripts, crucial for the study of Mughal painting, are kept in the collection of the Cleveland Museum of Art, and most of their folios have never before been shown.

Works Created for Emperor Jahangir

The story of the Mughals continues with works made for and collected by Emperor Jahangir (the name Prince Salim took after the death of Akbar in 1605), his son Shah Jahan (fig 4), and grandson Alamgir (r 1658-1707). This period spanning the 17th century saw the production of some of the most exquisite paintings and objects. Textiles, courtly arms, garments, jades, marble architectural elements, and porcelains bring to life the painted depictions of the Mughal court’s refined splendour at the height of its wealth.

Concluding the exhibition of Mughal and Deccan paintings is a large dramatic gallery, painted black in keeping with depictions of the interiors of 18th-century Mughal palaces, with paintings framed in gold, hookah bowls, enamels, a vina, lush textiles, and a shimmering millefleurs carpet.

The assemblage celebrates the joy in Mughal art of the mid-1700s. The scenes predominantly take place in the world of women (fig 5) and the harem, where the emperor Muhammad Shah (r 1719-48), who was largely responsible for the reinvigoration of imperial Mughal painting, grew up, sheltered by his powerful mother from the murderous intrigues that racked the court after the death of Alamgir in 1707.

Publication on Mughal Paintings by Cleveland Museum of Art

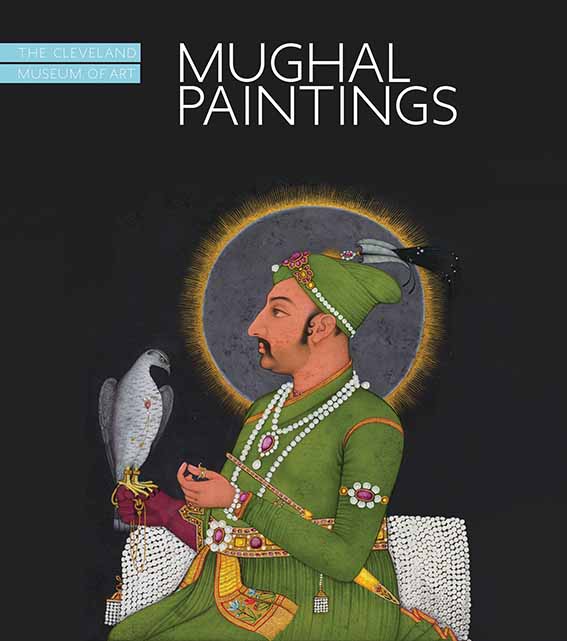

The selection of paintings and the object labels have been informed by decades of research and scholarship by the contributors to the catalogue published to accompany the exhibition. The publication Mughal Paintings: The Cleveland Museum of Art presents 401 full-color illustrations of works in the collection of the Cleveland Museum of Art. The volume includes all 95 Deccan and Mughal paintings from the Benkaim Collection, each shown recto and verso, uncropped, with translations of every text, inscription, and work of calligraphy.

Essays on Indian Art on Cleveland’s Website

Essays on the Cleveland Museum of Art’s website explore this subject. The first essay by Persian literary historian Mohsen Ashtiany is a thrilling and erudite account of the life of the warrior hero Rustam from the Shah-nama as told through the works of art on view in the exhibition. His essay sets forward the essential Persian underpinnings of Mughal painting.

Indian painting historian Catherine Glynn explores the extraordinary process of how the story of the Prophet Joseph of the Hebrew Bible was folded into the Islamic mystical romance tradition and how it resonated with court artists in India from the first decade of the 1600s until the end of the 18th century. Distilling essential information from his monograph dedicated to the Mir’at al-quds in the Cleveland Museum of Art, Pedro Moura Carvalho explains the art of a remarkably ecumenical moment in the history of India, when both Akbar and his son Prince Salim took keen interest in understanding through debate, text, and images the life and miracles of the Christian messiah.

Another essay on the story of the Mughals in the paintings in the Cleveland Museum of Art aims to give a readable, broadly sweeping account of their history and art based on primary sources and new research. Social issues of gender, race, and substance abuse, along with an exploration of the motivations for making paintings at the Mughal court are included alongside descriptions of ravishing details from the works themselves.

Marcus Fraser, a specialist in Islamic art, served as the content editor of this essay and generously contributed his insights and a penetrating introduction to the entire volume. Social historian Ruby Lal’s research on the lives of women at the Mughal court informs her interpretation of harem scenes that counterbalances orientalist views of eroticised exotic spaces. She understands paintings previously considered overly romantic or escapist instead to be imagery of pleasure and play denoting the realm’s prosperity and abundance.

These distinguished scholars from a variety of backgrounds and disciplines tie together the paintings in engaging narratives that provide fresh perspectives on the history of Mughal painting. Like Akbar, who commemorated the millennium of Islam with a spectacularly illustrated book, his Tarikh-i Alfi (History of a Thousand [Years]), the Cleveland Museum of Art marks its centennial with this publication and exhibition of works intended to delight and amaze the viewer.

Five essays complement the individual painting entries in the museum’s collections online at

www.clevelandart.org/artcollections