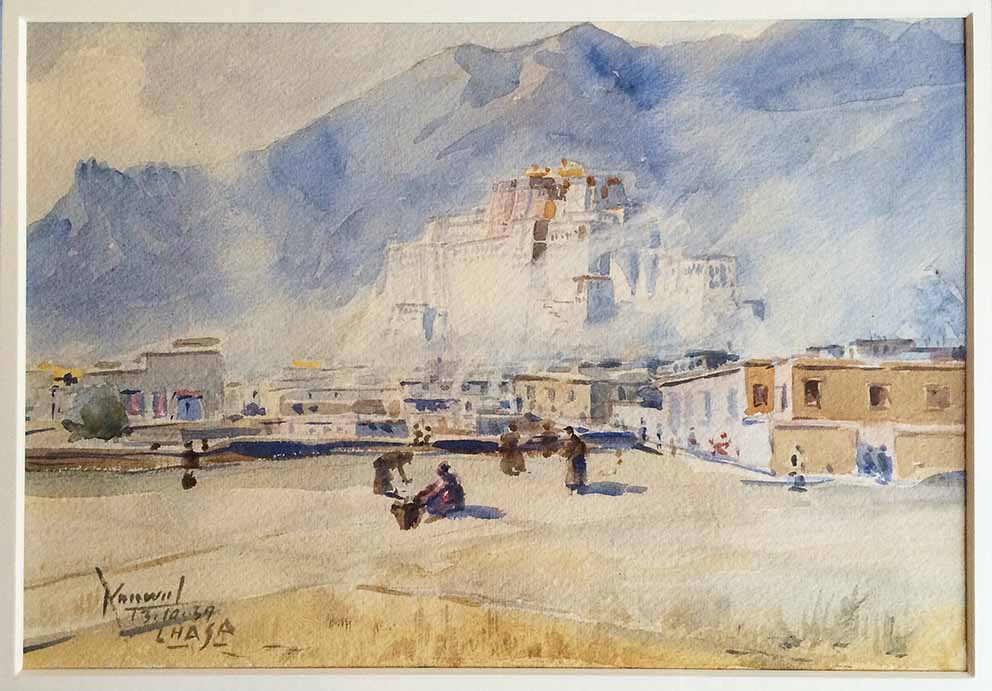

‘Architecture is deeply connected to our impression and experience of places. While we may never visit these sites ourselves, we often become acquainted with them through encounters with images on postcards, souvenirs, and various forms of media. In Lhasa, Buddhist pilgrims and other visitors created images focused on the capital’s striking landmark buildings to recreate and convey their experience of this important religious and political centre of Asia.’ Exhibition curator Natasha Kimmet

Shangri-La is somewhere in Tibet according to Lost Horizons, the book that started it all. It was a village, it turns out, a place of great beauty, peace, harmony and longevity. Oddly enough, this invented place had peculiarly Western amenities, such as modern conveniences, a grand piano and a harpsichord. It is not known where from whence the author took his inspiration, but a relatively sure bet was Lhasa. From the 18th century on, Westerners had visited Tibet as well as into the 19th century, mainly the British from colonial India. Western visitors increased greatly in the early 20th century and included people such as Kermit Roosevelt, President Theodore Roosevelt’s brother who brought back thangka from his visit. Many Westerners knew of Tibet and Lhasa, but only a very few had actually been there and of all the sites to be visited, the supreme one was the great Potala in Lhasa – a fortress, a temple and a palace, the residence of the Dalai Lama and his extensive staff.

Marpo Ri hill rises some 425 feet above Lhasa and the Potala, some 560 feet above that, looms a total of some 1,000 feet over the entire Lhasa Valley, making it the most impressive structure in all of Tibet. Early legends tell of a cave in Marpo Ri in which dwelt the Bodhisattva Avalokitesvara, Chenresi in Tibetan, Guanyin in Chinese and Kannon in Japanese. It was first used as a meditation retreat by the Tibetan ruler Songtsen Gampo, who in 637 built a palace atop the hill that stood untouched for over 1,000 years.

From 1635 to 1694, during part of the reign of the fifth Dalai Lama, the Potrang Karpo, or White Palace, and the Potrang Marpo, or Red Palace, were completed, a monumental effort that required the labours of more than 7,000 workers and 1,500 artists and craftsman. Even though the 13th Dalai Lama renovated many chapels and assembly halls in the White Palace and added two stories to the Red Palace, the exterior, as finished by 1694, remained unchanged to this day.

The Potala was only slightly damaged during the Chinese in 1959, and, unlike the majority of monasteries in Tibet, the Potala was not sacked and destroyed by the Red Guards during the 1960s and 1970s, the most criminal being the great monastery at Densatil. This was apparently through the personal intervention of Chou En Lai. It is not so remarkable that Chou En Lai interceded in sparing the Potala from the Red Guards. Although he was a powerhouse in the Chinese Communist Party, he had a cultural background that was and even now is not generally known: he was directly descended from the imperial Ming family and in his childhood the cultural and intellectual background of that family was passed along to him.

The period of Deng Xiaoping was one of great openness in Chinese society and when it became legal to privately own works of art there was an explosion of great and early Tibetan art in the hands of Western dealers and the auction rooms in Hong Kong, New York, London and in Continental Europe. Not a coincidence. I clearly remember that when I was handling Himalayan art at Sotheby’s New York, the oldest thangka on the market were 17th/18th century and early gilt images were great rarities. Things were to change forever soon thereafter but the changes were to have ominous overtones.

‘You have to hate or fear something a lot to do what China did to Tibetan Buddhism’ is a direct quote from Holland Cotter’s

2 February 2014 New York Times coverage of the Golden Visions of Densatil exhibition at the Asia Society. Before the Cultural Revolution there were thousands of monasteries in Tibet, but afterwards there were less than 10. The destruction of the Densatil was certainly a cultural crime of international proportions, but before its destruction, many of its great works of art were very carefully removed. The buildings and the remainder were consigned to the flames, but from the ashes numerous heavy copper alloy plaques with religious imagery, now with their original gilding melted away, were retrieved and have found their way into Western collections.

The majority of the art that was saved came from four 10-foot stupa inside the main hall. It is presumed that the art that was saved went into the hands of military commanders, but, based on credible sources, the main individual was a commanding general who had his share shipped to Beijing and stored in his warehouse. There it was to stay until the ownership of art was legal and the general’s death occurred; these treasures passed into the hands of his daughter who still owns them. She began to slowly let these golden treasures creep onto the art market where they were sought after avidly, creating Densatil almost as a household name.

Interestingly enough, the Chinese authorities have always been on a dogged search for Chinese works of art that they feel were removed from China illegally and have taken legal measures to have such pieces ‘repatriated’. Even though Tibet is an ‘autonomous region’ of the Chinese People’s Republic, not one word has ever been raised by the Chinese about any work of Tibetan art in the West.

The Rape of Tibet is almost complete now, what with its art plundered, monastic life crushed and the Sinification of Lhasa and elsewhere by floods of new Chinese residents imported by the Chinese. However, there is a code of silence among the many collectors, dealers and museums with Tibetan collections. The fact that on one side are many very willing recipients of rare Tibetan art and very few willing Tibetan donors. That is the stalking horse of ethical impropriety that is being politely ignored on an international scale.

This exhibition, however, is about ‘what is’, rather than ‘what was’. It is the first exhibition to explore Tibet through visual representation by the use of drawings, paintings, and photographs of Tibetan landmarks, etc – Lhasa in particular – that were created over a three hundred-year period by both Tibetans and Westerners. By the use of fifty works of art from its own collection and from public and private collections in the US and Europe, The Rubin has brilliantly accomplished much more than just a show-and-tell. The Rubin has transmitted the magic of Lhasa to a location many miles away through the use of not just paintings, drawings and photographs, but such almost-mundane objects as pilgrim maps, photo albums and works of art. All are for the purpose of bringing this magical city to life, not just the Potala, but also the Jokhang Temple, and Samye Monastery.

Some of the illustrative works include a late 19th/early 20th-century thangka of the Demoness of Tibet from the Rubin Collection; a painting, circa 1857, of the Samye monastery commissioned from a Tibetan monk by a military officer from India, Major William Edmund Hay (1805-1879), on loan from The British Library in London, and an album of photograph by Tsybikoff, circa 1900-1901, of the

Tashilhunpo Monastery.

BY Martin Barnes Lorber

From 16 September until 9 January 2017 at the Rubin Museum of Art, New York, www.rubinmuseum.org

Share this:

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window) Email

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window) LinkedIn

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window) Tumblr

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest