To celebrate the 150th anniversary of the establishment of the Meiji era (1868-1912) and Meiji Art, this exhibition highlights the explosion of creativity in Japanese arts at a time of transition in the country’s history. The period when Japan opened to the West, and swift modernisation, industrialisation, and militarisation followed, which consequently brought growth in the cities.

Over 350 works of art are on view, on loan from French and international institutions, such as the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Musée d’Orsay, Victoria & Albert Museum, and the British Museum, as well as the Khalili Collection of Japanese Art.

The New Emperor

In 1852, Prince Mutsuhito was born in the old imperial palace of Kyoto, the sole survivor of the six children born to the emperor Komei, his father. He is better known under his throne name of Meiji (enlightened rule). The new emperor inherited an exhausted system that had ended with the collapse of the bakufu (the isolationist military government headed by the shogun Tokugawa). In 1868, a new model of governance inspired by the West was declared that restored ‘imperial rule’. From this point, Japan opened up to the world and in just a few decades switched to a Western-style industrial system and economy. This sweeping transformation involved every aspect of Japanese society, overturning the established system, and encouraged the adoption of Western dress and influences.

The first section of the exhibition looks at this early history and the establishment of the Meiji period, including the influence of the imperial system on society and explores the complex issues of the time – politically, socially, and economically. It also questions whether it was indeed the emperor who guided this policy, or an oligarchy working in the shadows. A new order had been created and society had reacted to these changes.

Before the Meiji era, the Japanese people were defined by where they lived and how they spoke, or which province they came from and their regional dialect. The new era forced change and people started to have the feeling of belonging to a nation, united under the great imperial project. Presented officially as the ‘restoration’ of power, a repeal of the military government that was established at the end of the 12th century, Meiji was, in fact, a plan for reform, to create a nation-state and a powerful empire, grouped around the new emperor.

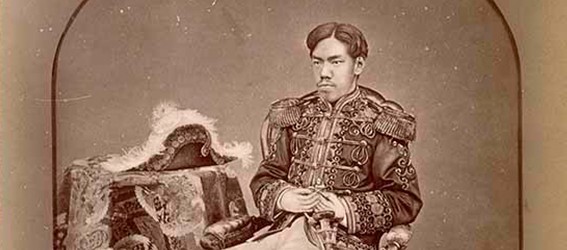

This idea was widely distributed through the newspapers and judicious use of photographs. A popular photograph of the time showed the emperor wearing a Western-style military uniform with numerous decorations and orders, sitting on a French-style armchair draped with a Japanese textile. Japan wanted to build a nation-state capable of standing up to Western powers and its other neighbours in Asia – illustrated by the slogan the new government introduced: fukoku kyohei ‘rich country, strong army’.

The Opening Up of Japan

When the ports began to welcome foreigners, Yokohama, Nagasaki, and Kobe served as models for the modernisation of other big cities in Japan. Western architecture was also adopted for official buildings, banks and department stores; a new type of hotel was designed to accommodate the growing number of foreigners and businessmen visiting the country and tourist hotels were built to enjoy Japan’s beautiful landscapes.

At the heart of the cities, this new architectural style, along with Meiji art, became synonymous with modernity. Industrial processes were quickly introduced. Japan’s main export product at the time was grège silk (raw silk), so the Tomioka Silk Mill (Tomioka Seishijo) was established by the government in 1872, to produce modern machine silk reeling in response to the demand, and increase productivity by using technology brought from France.

In tandem, communications were developing fast and the Meiji era saw the start of the railways in Japan, with the opening of the first line from Yokohama to Tokyo in 1872.

Political Unrest in Japan

The end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century saw political unrest across the world and Japan was caught up in its own fight for territory. Another section of the exhibition looks at the wars with Korea, China, and Russia. Conscious of their inferiority to Western armies, from around 1850 onwards, many governors of provinces and the shogunate had begun to strengthen their reserves in an effort to modernise.

After the Shimonoseki Campaign of 1863-1864, a series of military engagements against the joint naval forces of Great Britain, France, The Netherlands and the US, a national defence policy became a priority. With the dawn of Meiji, Japan also sought to expand its empire and influence in the area. In 1874, the Japanese Navy led an expedition to Taiwan and annexed the Ryukyu Islands in 1879. North of Hokkaido, Japan also claimed the Kuril Islands in exchange for the peninsula of Sakhalin that had been ceded to Russia in 1875. In 1895, the Treaty of Shimonoseki ended the first Sino-Japanese War, in which China ceded Taiwan, the Pescadores Archipelago and Manchuria (Liaodong Peninsula).

First Sino-Japanese War

The first Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895) was fought between the Qing Empire and Japan for influence over Korea. However, Japan’s complex relationship with Western powers led to the Triple Intervention (Russia, France and Germany) also lead to war in 1895, where Japan retreated from the Liaodong Peninsula. Regional influences and domination became increasingly complex. The turn of the century thus saw a rise in conflict: war was declared on the weakened Chinese empire during 1894-1895, the start of the Russo-Japanese War in 1904-1905 and Japan’s annexation of Korea in 1910.

Japan’s Artistic Heritage

The exhibition also explores the rise in popularity and demand for Japan’s artistic heritage in Meiji art, which was most visibly seen abroad in the late 19th century at the universal and international exhibitions. After exhibitions in London (1862) and Paris (1867), where Japan and its products had aroused great curiosity, the new imperial government became aware of the role that these exhibitions could play in redressing a difficult economic situation at home due to the decrease in patronage by the large and influential aristocratic families.

Artistic production played a vital role in enhancing the reputation and prestige of the nation and helped to redress the trade balance caused by the cost of modernisation by creating an export demand. Therefore, the government carefully selected the artists, objects, and products to represent Japan in the exhibitions in Vienna (1873), Philadelphia (1876), Paris (1878, 1899 and 1900) and Chicago (1893) and to show off their new Meiji art.

To emphasise the uniqueness of the country, the Japanese pavilions were modelled on traditional buildings – to create a fascination for the country and showed the uniqueness of Japan. The plan paid off and the universal exhibitions were a commercial success, as Western audiences were not only fascinated by this long-isolated country, but were also entranced by the objects that were offered to them (another attraction was the advantageous price).

The Craftsmen of Japan and Meiji Art

Craftsmen in Japan had always been recognised for their skills and the quality of their work. The idea of Japan in the West stems from this time – goods that showed time-consuming perfection and a painstaking and patient execution of craft, objects showing a new aesthetic and sense of the use of space in design. In the Meiji era, due to the march of science and industrialisation, this skill and taste was able to be married to create Meiji art with a remarkable progression in techniques in the fields of metalwork, lacquerware, and cloisonné objects.

The government played a vital role in the development of these technical skills by encouraging and sponsoring education and technical schools – National Industries Exhibitions were organised in all the main cities of Japan to encourage competition and growth in domestic and export industries. The first National Industrial Exhibition was held in Tokyo in 1877, featuring products appropriate for the integration of Western technologies into Japanese industries.

Western Modernisation

However, in the face of Western modernisation, an art movement grew up in Japan in response to this change, which sought to define and affirm its cultural identity by turning to its past, creating a new style of Meiji art. At home, there was renewed interest in the Rinpa school that was in decline by the end of the 19th century. The burst of creativity and art during the Meiji era reaffirmed Japan’s own identity through producing arts and crafts that were deeply reverential to its past. This can be seen in the traditional images often chosen for surface decoration, such as the world of the samurai, or images of Edo-period courtesans of the floating world, all memories romanticised from an earlier age that could be used on modern commercial products for export. The lure of Japan’s past sold in the West.

Establishment of Cultural Institutions and Publications

At the same time, cultural institutions such as museums, art schools, and art history magazines were established – all supporting the culture of Japan and its ancient cultural past, supporting the revival in such crafts as lacquerware and basketry. These crafts and skills were also recognised, honoured, and given a new perspective in society. In 1871, the Daijo-kan (Great Council of State) issued a decree to protect Japanese antiquities called the Plan for the Preservation of Ancient Artefacts and a second law was passed on December 15, 1897, that included supplementary provisions to designate works of art in the possession of temples or shrines as ‘National Treasures’. The laws of 1897 are now the foundations of Japan’s current designation and protection laws.

The Meiji period also saw Japanese painting (Nihonga) develop in a new way – works that use techniques and materials of traditional Japanese painting as opposed to Western style paintings. Nihonga was inspired by Japanese traditions and Chinese ink paintings, but also integrates Western influences, including Western perspectives and shading.

The movement also created an artistic community where painters, enamellers and ceramists often worked together rather than alone. The Tokyo University of Fine Arts, founded in 1885, played a vital role in the Nihonga movement, under the direction of the scholar Okakura Kakuzo (1862-1913), who became famous as the author of The Book of Tea (1906), a long essay linking the role of chado (teaism) to the aesthetic and cultural aspects of Japanese life.

With the American philosopher Ernest Fenollosa, Okakura sought to promote painting with a national character and to strengthen the links between painting and decorative arts. The work of the artist Watanabe Seitei, who spent several years in France, where he met Degas, is a prime example to show the relationships between decorative arts and painting. Linked to the rise in interest from abroad for all things Japanese, the craze of Japonism was born and signalled the globalisation of Japanese taste. This new aesthetic became the inspiration for many Western artists, who quickly adopted the trend and created hybrid works as their response to these new foreign works they saw, one of the most visible movements was Les Nabis, a movement emerged in late 19th-century France.

Buddhism in the Meiji Period

A section in the show looks at Japanese culture in another form. Religion, in the form of Buddhism, is explored from the beginning of the Meiji era, when violent anti-Buddhist reactions had led to the destruction of many temples. The exclusive promotion of Shintoism – the indigenous religion as opposed to the ‘imported’ Buddhism from China – saw the separation of Shintoism and Buddhism, which had merged over centuries leading to a decline in Japanese Buddhist artistic heritage.

However, this change was resisted as Buddhism was, and remains, deeply rooted in the population and any attempt to change people’s faith was soon reversed. On another front, artistic Buddhist works were also sought by the West, with such collectors as Émile Guimet (1836-1918) buying directly from Japan. Guimet was commissioned, in 1876, by the minister of public instruction in France, to study the religions of the Far East and Musée Guimet, today, contains many works of art from this period and from Guimet’s own collection.

Folk art and popular consciousness are explored in a section entitled ‘Yokai, Ghosts and Demons’. During the Meiji era, yona oshi ‘renewal’ is a key phrase that characterises how popular culture could flourish, despite the rigidity of the imperial system. Life for normal citizens, in the early Meiji, was full of turbulence, change and complexities – there were administrative reforms, the remodelling of the property tax and a contraction in the number of cities and villages.

During these times of uprooting, devotion to spirits – kami – closely linked to the past and the ancestors was very strong. Monsters (yokai), spirits and ghosts, were either reassuring and protectors, or, conversely, expressed the fears and dangers that proliferates at the time. Buddhism was also under threat at this time from the new imperial order, so it is understandable the population looked to its past beliefs for comfort and explanation. An iconic artist, painter and caricaturist of the time, who expressed these fears, was Kawanabe Kyosai (1831-1889), a kind of ‘Don Quixote’, who was personally persecuted because of his vehement opposition to the Meiji reforms, undergoing punishment and imprisonment for his satirical views and works.

The Meiji was a time of great change for Japan, which used its artistic heritage, as one response, to help the country move forward to meet the challenges and demands of the new century. The Meiji period transformed Japan from a medieval, feudal past to a modern, international country, equipped to meet and compete in the modern increasingly globalised world, without entirely giving up its own identity.

Meiji: The Splendours of Imperial Japan, until 14 January 2019, at Musée Guimet, Paris, guimet.fr