There was a moment in Kurt Neumann’s classic 1958 sci-fi horror movie, The Fly, when Vincent Price – the actor known for his roles in such films – delivered an introduction to the audience, ‘It would be unfair … to show you anymore of what went on in that laboratory where a man actually dared to play God’. The man was a scientist whose experiments in transferring matter through teleportation had gone wildly wrong when a fly accidentally entered the machinery culminating half-man, half-fly being teleported across the laboratory. I was reminded of this when I visited the artist Li Shan.

I visited veteran artist’s studio in May this year, when he showed me his grotesque life-size sculptures that were half-man and half dragonfly, and which, if he had his way, he would happily turn into living creatures. They swung menacingly from the low ceiling in a side room off his studio, as he quietly confided that he wanted to improve on ‘God’s Creation’.

BioArt Project – Misfortune

I had first seen a swarm of these grotesques 18 months previously, hanging in the atrium of Sydney’s White Rabbit Gallery. Misfortune 2 (2017) had the heads and wings of dragonflies and the bodies of men, and were from the artist’s ongoing BioArt project that began in 1993. BioArt was an attempt to manipulate and transplant genes between species to arrive at a nobler version of mankind than that which had been created by God.

It was to be the ultimate fusion of science and art spurred on by Dolly the Sheep, the first mammal cloned in 1996 and subsequently followed by various other cloned animals. I had decided then that next time I was in China I would find Li to discuss these hybrid creatures that were a world away from his popular 1980s pop-art paintings of an effete and vividly coloured Chairman Mao (his Rouge series), with pouting lips and rouged cheeks and eyes lined with mascara, which had made Li’s name and for which he is still most widely known. I was to find Li in the most unlikely of places, in Lingang New City, 60 kilometres south of Shanghai.

Lingang New City

Lingang New City is a ‘Ghost City’, one of dozens that have sprung up around China in recent years. Built entirely from scratch since 2003, it sits on land reclaimed from the sea at Pudong. Designed around a vast circular man-made lake the various buildings spread out like ripples. Rather grandly, the German architects claim Lingang was inspired by the ancient city of Alexandria, one of the Seven Wonders of the World.

In less grandiose terms Lingang New City, when finished, will be a satellite city for Shanghai and will take pressure off the Shanghai’s rapidly growing population. 800,000 people are projected to be living in Lingang by 2020. Currently the wide boulevards are predominantly empty of both people and traffic and finding a taxi on the street was an insurmountable challenge, as I was to discover later in the day.

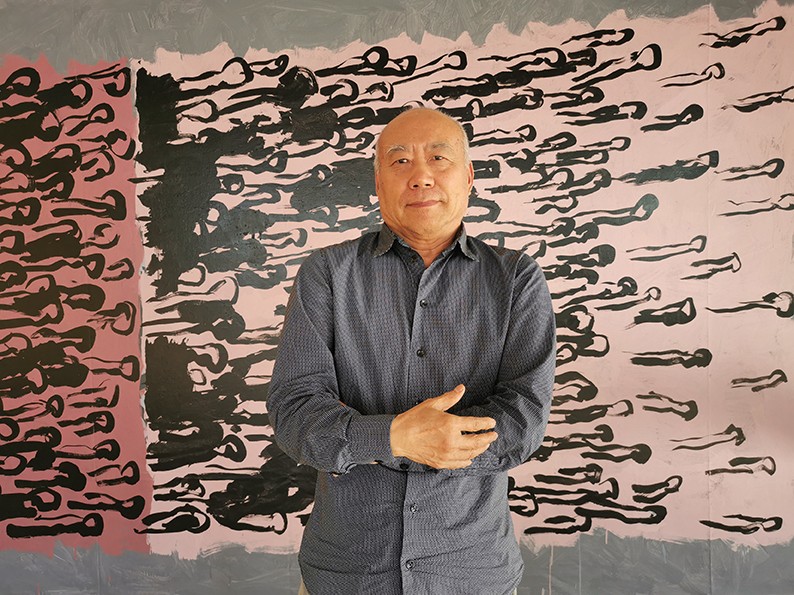

At 75 years of age, Li Shan can be considered a veteran contemporary artist, who had doggedly pursued his practice through the years of the Communist party’s ascendency in China (he was seven years old in 1949 when Mao Zedong declared the creation of the People’s Republic of China), through the years of the Great Leap Forward (1958-62), through the turmoil of the Cultural Revolution (1966-76) and the introduction of Deng Xiaoping’s opening up, post Mao’s death in 1976, that introduced capitalism with Chinese characteristics, to the country. But there he was in Lingang, in a studio on the 4th floor of the Art Lingang Museum building, one of several, severe, geometric blocks surrounding a communal garden with brightly coloured street furniture. But few people.

The museum’s reception was whisper quiet. There was no art on view either and a solitary concierge sat at a marble topped desk, doing nothing in particular. I asked for Li Shan’s studio and was directed to the fourth floor were a long featureless hotel-like corridor led along to a small, extremely fit looking 75-year-old man who vigorously waved at me. It was Li Shan. Tucked behind him was his diminutive wife, who also waved.

Li Shan’s Studio

Li’s studio is large – 325 square metres – but seemed larger and I could see the lake from several windows. The space was exaggerated by the sparseness of its furnishings – in the middle was a solitary ornate dining table and four chairs – and the low ceiling emphasised the studio’s horizontality. Shan, speaking Mandarin through an interpreter, immediately bemoaned this lack of ceiling height, a complaint he spun out with some irony given that he had worked there for five years. It limited the size of the paintings he could make, he claimed.

Several movable particle board walls created various domestic areas; there was a kitchen, a bedroom and a living area. There were no books. No bookcases and nothing on any wall, other than one large work-in-progress, from Li’s ongoing Reading series. It all looked a touch impermanent, unlived-in, and clinically sterile. It was not his home, he explained. He lived on the other side of Shanghai but, because it took two hours each way by train, he often stayed at the studio.

The studio, he said, was supported by the local Pudong government district and much of the building was given over to artist studios, at competitive rents. What we in the West would consider a ‘sweetheart deal’. We sat at the dining table. He spoke exclusively in Mandarin and I was soon captivated by the gentle flowing cadences and rhythms of his voice, even though I did not understand a word that he said. But he spoke slowly and sonorously, albeit at some length, and the interpreter easily kept pace with him.

Li Shan, a revered figure in the history of Chinese contemporary art, was among the cultural pioneers of both the avant-garde and political pop movements of the 1980s where his most significant paintings were appropriated propaganda pictures of Mao that Li turned into an androgynous looking Mao, often portrayed with a lotus flower. Painted in a style reminiscent of Andy Warhol’s screen-print portraits from the 1960s, Li Shan’s political pop mixed western pop art with socialist realism that question the political and social mores of a rapidly changing China.

The Mao Series

The Mao series cemented Li’s reputation and he capitalised on their popularity and what were once, one-off original paintings, became over the ensuing decade, a series of vividly coloured screen prints. In 1993, Li was one of 10 Chinese artists – including Xu Bing and Wang Guangyi – to be among the first group of Chinese artists to show at the Venice Biennale. It was paintings from the Rouge series that went with Li.

The ubiquitous propaganda images of Mao along with Mao’s strident ideology, had formed a back drop to Li’s life. ‘Even at primary school you had to worship him and the flag every morning. Mao’s image was always there while I was growing up,’ Li explained. Among the most obvious features of Li’s Mao paintings were the pouting red lips, delicate facial features, and the jauntily worn Mao cap. I pressed Li on why he portrayed Mao this way. His answer was a little circuitous as he drew an analogy between his paintings of Mao and images of the Buddha. ‘The Buddha in China over centuries after being introduced from India, was somehow transformed from male to female. I painted Mao being transformed from a male Mao, to a female Mao,’ Li continued. ‘Everyone saw Mao as a divine god. I wanted to destroy that idea’. And the lotus flower? ‘The flower does not represent anything. Mao means nothing by himself either. But Mao with the flower means everything!’, Li enigmatically and mischievously, stated.

Many contemporary artists of the period appropriated propaganda images of Mao and I wondered if Li’s versions had ever attracted any official opprobrium. ‘At the time, when I did the Mao paintings, I was fortunate to be able to create freely. I did not suffer from any official challenge on a political level. Many people empathised immediately with what I was doing and shared similar feelings about Mao. For me the Mao paintings simply related to the times I had lived through,’ he elaborated. Their popularity has endured and Li, with some prescience, had two, tucked safely away, for a rainy day.

Li Shan was Born in Lanxi Village, Heilongjiang Province

At heart Li is a country boy. Born in Lanxi village in Heilongjiang Province in north-eastern China, he lived in a house made from mud and straw. Not particularly talented as a boy his parents did, however, encourage him to draw, often before going to school. ‘I remember painting a cartoon of the US President Eisenhower on cardboard. The Korean War was on so it must have been 1951,’ he said. He entered Heilongjiang University in 1963, where he briefly studied Russian before dropping out. ‘I had no gift for languages and just did not like it there. So I quit and decided to study fine art at Shanghai Theatre Academy starting in 1964. The reason I chose art was during high school we had a blackboard culture where you had to make special designs for the blackboard. I created a design and the teacher commented how gifted I was. I believed this. That is how I got the confidence to go to an art school,’ he remembered.

The Cultural Revolution

In 1966, every corner of China was engulfed by the Cultural Revolution, led by student revolutionaries charged by Mao to rampage through the country in a frenzy of cultural destruction. Li became a Red Guard too. ‘It was impossible not to be a Red Guard,’ he said. Schools and universities closed down for a decade. ‘I wanted to do some experimental art, but it had to be on a small scale and it could not be circulated. If I had been found out, I would have been in trouble. At that time only main stream, very academic work was accepted,’ Li explained.

Li Shan and the Pursuit of BioArt

In 1993, Li gave up his decade’s long familiarity with painting to develop and pursue BioArt, which initially explored the theoretical idea of how science and art could come together to mix human genes with those of other species to create ‘new and better forms of life’. Li dabbled in mixing and transplanting plant species but steered clear of mammal cloning and the ethical firestorm that would ensue. Working with bio-scientists his early experiments with gene substitution led to a living crop of deformed and grotesquely blackened gourds, Pumpkin Project (2007). Hardly the Utopia he had originally envisaged and certainly no improvement on God’s originals.

Li remains closely in touch with scientists. ‘I am thinking everyday about bio-art and its potential to develop new life forms. The science progresses daily,’ he said. As he spoke it all sounded like a fruitless search for an elusive Utopia. But given the nature of the controversy surrounding genetic engineering one cannot help but wonder if his nascent experiments, to meld science and art, can be anything other than a dead-end journey.

Li Shan’s Exhibition at Shanghai’s Power Station

More recently in 2017, at Shanghai’s Power Station of Art (PSA), Li showed Photoshopped photographs of what genetically engineered insects might look like that also served as blueprints for future experiments. He also showed two installations, Smear 1 (2017), 1,100 pots of rice plants and Smear 2 (2017), 1,100 potted stalks of corn, that he had grown from genetically modified seeds. ‘I worked with a science team at Fudan University. We selected the seeds and then added the genes,’ he explained. The dead remnants of both installations were in his studio, bathed in harsh sunlight from several windows. The plants had long since gasped their last and were parched remnants of their former selves. Alongside the corn, were tangled, unruly dead hummocks of rice. Both looked more end of the world, than brave new world. Their altruistic expediency now long gone.

High in the atrium at the PSA’s entrance though had hung 60 of Li’s human torsos, with wings and bulbous insect heads. Gripped with some excitement, Li sprung up from the table and beckoned me to follow. We went into a large side room where, somewhat chillingly, two of these life-size, mutant, silicon monsters hung from the low ceiling, their attenuated limbs low enough to brush one’s face. Up close their heads were bulbous and hairy and transparent wings sprouted from their backs.

But their lower bodies, from the waist down, were human, cast Li proudly announced, from his own body, complete with heavily accentuated male genitalia. In addition, a dozen or so coffin-like wooden boxes, that contained several more of the creatures, were stacked along one wall. It was like walking through an ossuary and it was a moment that Li seemed to relish. ‘God’s work is unfinished,’ he said. I was not quite sure what he meant by this, but if this were the results of his theoretical attempts to create better life forms, then it for me, had failed.

Li Shan’s days are free of any fixed routine. Some days in the studio are productive, others not so much. The day before I arrived the weather was dull and overcast, so he did not paint. Today, he felt good and said he would work on the large canvas pinned to the wall. At 75 years old, I wondered if Li had any intention of slowing down. His answer was abrupt. ‘I do not think there is much point,’ he stated. ‘I will not stop. I am thinking everyday about BioArt, because the science progresses daily I need to think about these things every day. If there is a breakthrough, I need to know and understand. The mystery is what attracts me,’ he elaborated. But throughout our talk there had been no mention by Li of the ethical challenges presented by BioArt’s dangerous ideas.

Such a conundrum aside, BioArt presents unfathomable consequences for the future as we move toward a moment when simulation transgresses into actual biological manipulation and Li’s humanoid creatures become a reality.

As Vincent Price also said in the 1958 movie, ‘Will everyone in the theatre hold on firmly to his seat, please’. It would be advice well heeded today, as Li continues to dabble in God’s domain.

BY MICHAEL YOUNG

For more information on the artist visit ShanghART’s Gallery