In the 1970s and early 1980s, Sotheby’s in New York and the auction houses in the UK and in Europe sold mostly late Utagawa School prints by Kuniyoshi (excluding his early works), Kunisada I aka Toyokuni III, Kunisada II and III, Yoshiiku, Yoshitora, Kuniteru, Kunisato, Kuniteru I and II, Kunitsugu and Kunitsuna either as accordion albums made by dealers in Tokyo for Western visitors, or in stacks which were valued by the inch. Here we look at a classic comparison of print masters – Kuniyoshi vs Kunisada.

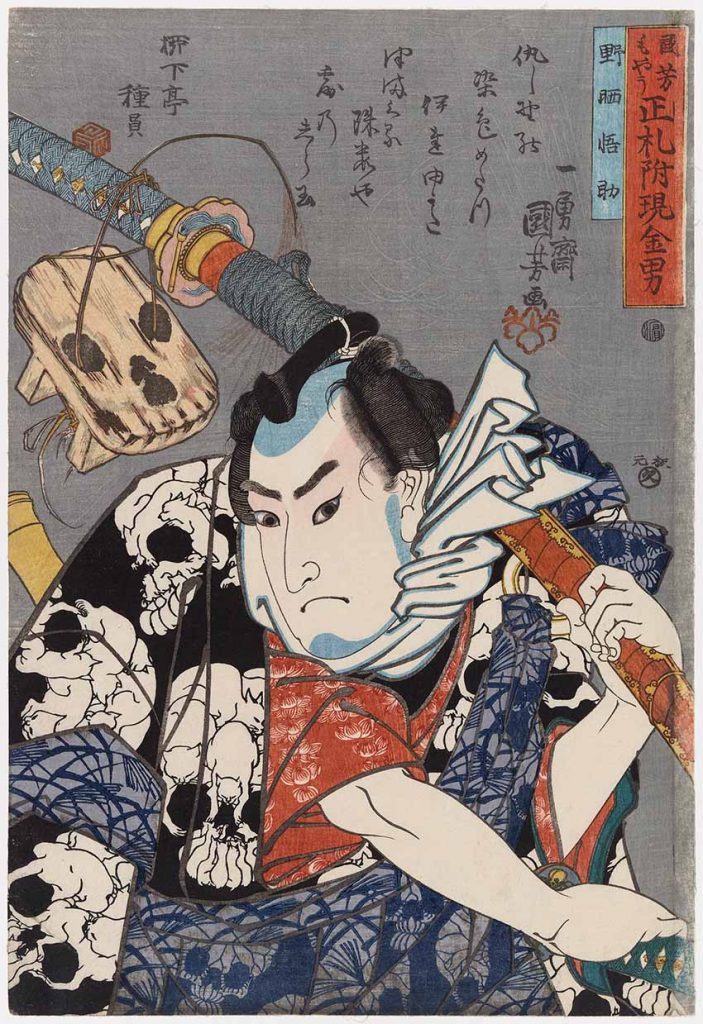

The Actor Prints of Kunisada

Ellis Tinios’ book, Mirror of the Stage: The Actor Prints of Kunisada (University Gallery, Leeds, 1996) discusses Kunisada in critical terms; another book, an earlier one, by the print scholar Arthur Davison Ficke, states in his Chats on Japanese Prints (1915), ‘This very undistinguished artist [Kunisada] was one of the most prolific of the ukiyo-e school. All that meaningless complexity of design, coarseness of colour, and carelessness of printing which we associate with the final ruin of the art of colour-prints finds full expression with him’.

The belief in the West about this group was that they were vulgar ‘unworthies’ and were known as the Decadent School. This belief remained firmly entrenched until late in the 20th century. There are two main reasons why the modern revision in judging these prints took place: Jan van Doesburg’s What About Kunisada? (1990) and Kunisada’s World (1993) by Dr Izzard, now owner of Sebastian Izzard Oriental Art in New York, specialising in the best of Japanese prints and paintings. In these works Kunisada concentrated on the elaborate printing techniques and style of portraiture of the ‘big heads’ prints that he produced near the end of his life.

Two Best-Selling Prints Masters of Ukiyo-e in 19th-century Japan

The related material of the Museum of Fine Art’s exhibition in Boston refers to Kuniyoshi and Kunisada, aka Toyokuni III as ‘The two best-selling designers of ukiyo-e woodblock prints in 19th-century Japan’. Due to their massive output, they were, indeed, the best-selling, but not the most famous in the long-term, this title belongs to Hokusai and Hiroshige I, both prized for their glorious landscapes, with Hokusai’s ‘Great Wave’ being just one example (and a highlight of a recent British Museum show, Hokusai: Beyond the Great Wave).

At the time, Kunisada was considered the most famous and most popular of all, a point of view that was reversed by time. Since this exhibition has been created as something of a Japanese art version of ‘Gunfight at the OK Corral’, what is missing from the 100 prints and five illustrated books (ehon) on view, from Boston’s own collection, are the beautiful landscape series that Kuniyoshi created in his early working life, The Life of Nichiren, Views of the Eastern Capital and the like. These are not included in order for the exhibition to concentrate on the street art of Edo, the prints of actors, courtesans, classical heroes and battle scenes.

Rivals in Prints

The exhibition casts Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1797-1861) and Utagawa Kunisada (1786-1864) as rivals, which they were, but not of the modern cut-throat variety. It was Kunisada who got Kuniyoshi to renew his efforts to create after about his 10 years of limited production, and it was also Kunisada who joined forces with Kuniyoshi years later to co-design several series and single prints. In any case, there was sufficient room in the market to absorb the constant flow of new prints from both of them, especially those by Kunisada whose total number of designs is probably over 20,000, an unimaginable number for an artist.

These days, museums are highly dependent on strong attendance figures to these exhibitions, as they are part of their main source of funding. Also, with the attendance at the exhibition, there is a strong possibility that viewers will wander the museum and view displays of vast categories of art from its world-famous collections. This almost guarantees return visits and possibly, membership, and of course, there is always the museum shop ….

The exhibition is a clever publicity stunt and the subject matter is not prone to attract those who have a deep scholastic interest in ukiyo-e prints, but rather those attracted by ‘action’ in competition. This plan will probably be extremely successful. The wish to attend is derived from the exhibition’s encouragement to the public to become involved in what is basically a popularity contest, but one that will benefit both the museum and the public at large.

Both Students of Utagawa Toyokuni I

Interestingly enough, both Kunisada and Kuniyoshi were students of Utagawa Toyokuni I (1769-1825). Toyokuni I, like his contemporaries Kita Utamaro (1753-1806), Isoda Koryusai (1735-1790) and Kitao Masanobu (1761-1816) specialized in depicting beautiful women, bijin-e.

Before the beginning of the 19th century, Toyokuni I, Koryusai and Masanobu depicted their subjects as tall, willowy and beautiful courtesans wearing simple but elegant kimono and with a restrained number of hairpins. Utamaro, however, specialised in half-length portraits of teahouse waitresses and the like, many being textbook-famous. By the early 19th century, however, tastes had changed and artists like Toyokuni I himself and Toyokuni II (1777-1835), Keisai Eisen (1790-1848) and Kikugawa Eizan (1795-1844) depicted courtesans as coarser women in elaborately-patterned kimono and with an exaggerated number of hairpins, creating a Japanese version of the blatant, ‘come hither’ look.

Frequently they were depicted with their attendants en promenade in public. Prostitutes have always utilised notice for business purposes, so this is nothing new in the world of Japanese prostitutes or courtesans (as their bespoken colleagues are called). Particularly ‘famous’ prostitutes were depicted by Eisen, Eizan and Kunisada, but not by Kuniyoshi. Kunisada went so far as to depict variations of them in his series Thirty-Two Physiognomic Types in the Modern World.

As a sign of the universitality of this profession, well-known prostitutes in Renaissance Venice advertised themselves by appearing in public in sumptuously elaborate robes and coifs and accompanied by two attendants. Why two? Because they the courtesans wore foot-tall shoes and needed them to keep from toppling over. It was this colourful ‘floating world’, ukiyo-e, of Edo prostitutes, wrestlers and actors that monopolised the vast majority of Kunisada’s opus. Kuniyoshi, however, took a different path in his works.

Kunisada’s First Print Was in 1807

Kunisada became a pupil of Toyokuni I somewhere between 1801 and 1805 at age 15 to 19 because Toyokuni saw remarkable talent in him. As proof that Toyokuni was right, Kunisada’s first print appeared in 1807. His first book illustrations and actor prints appeared in 1808-1809 and in 1809 his first prints of beauties (bijin-e) and pentaptychs of views of Edo appeared.

A reference was made about him by a contemporary source as a ‘star attraction’ and by 1813, at age 26, he was considered part of the ukiyo-e firmament in second place behind his Master, Toyokuni I. His early prints tended to be half-length portraits of beauties, very much in the manner of Eisen and Eisen. For the rest of his life he churned out prints whose subjects were kabuki actors in single-sheet portraits from different roles or, more commonly as triptychs depicting a specific scene from a specific play with several actors – his most common milieu.

Kuniyoshi is not known for this and his triptychs are almost always devoted to scenes from historic battles or the supernatural phenomena which course through Japanese culture. Another specialty of Kunisada’s was the coverage of the latest fashions among women, a subject as important then as it is today. Towards the end of the exhibition is a fitting closure, a poignant memorial portrait of Kunisada I by Kunisada II depicting his Master seated on a mat in a simple kimono holding a rosary.

Both Began Designing Book Illustrations

Kunisada, 10 years older than Kuniyoshi, began his apprenticeship around 1801 at the age of fifteen, while Kuniyoshi began his in 1811, also at the age of fifteen. From the very beginning Kunisada was considered an enfant savant while, some 10 years later, Kuniyoshi was not, but they both began being put to work designing book illustrations (ehon).

Next came designs for bijin-e or pictures of beautiful women and their results reflected new way of depicting them – some full-length and some half-length, all very much in the new, bolder style than that of the preceding masters. The period of about 1812 through the late 1820s was dominated by this bold and sometimes excessive style.

From 1818 through 1827, Kuniyoshi produced only a few ehon, actor prints and bijin-e because he was receiving almost no commissions from publishers. He had been so reduced in state that he was forced to sell his tatami mats in order to eat. 1827 proved to be a turning point in his career when, much by accident, he met Kunisada. The highly successful actor, fully aware of Kuniyoshi’s plight, entreated him to renew his efforts to have his designs accepted by the publishers.

Armed with his newly found determination and a number of new designs, his career skyrocketed and it not long before he also became wildly popular. His designs differed greatly from Kunisada’s palette of actors, bijin-e and wrestlers as they tended toward dynamics, such as battle scenes, monsters, the supernatural, always a big draw in Japanese culture, and tattooed warriors from tales of classical heroes. He had a quirky and compulsive side with his prints of cats and cats as kabuki actors, peculiar depictions of people and occasionally his cleverly disguised, but still dangerous, political satires.

Kuniyoshi’s Thirty-Six Views of Mt Fuji

He did not restrict himself to independent single-sheet prints or triptychs of the normal subject matter, but produced series of prints in the 1830s of landscapes, very much in the tradition of Hokusai. Besides Life of Nichiren, he also created Thirty-Six Views of Mt Fuji, following Hokusai’s example, and Famous Products of the Provinces, in which he incorporated Western perspective and shading.

These were probably derived from European prints imported by the Dutch to their trading station at Deshima. Also at this early period he produced wonderful prints of birds and animals executed on connected vertical sheets (kakemono-e) for maximum impact. These were designed along the lines of the Nanga School of painting which took its inspiration from Chinese landscapes and depictions of birds and animals. It was in the 1840s that he turned his attention to actor and ‘action’ prints, especially in triptych format.

Kunisada Tryptichs

Whereas Kunisada created triptychs of actors, almost all of Kuniyoshi’s triptychs were either battle scenes, both on land and sea, or scenes of the supernatural. Tales of the supernatural were standard fare in Japanese mythology and folk belief and many of these creatures were depicted in so many forms: horned demons, giant spiders, foxes disguised as beautiful women as well as a coterie of imaginary beings that remind one of the opening line of that old Scottish prayer, ‘…from ghoulies and ghosties and long-leggedy beasties and things that go bump in the night …’.

After his death, Kuniyoshi left behind his six pupils, now independent artists: Yoshitoshi, Yoshitora, Yoshiiku, Yoshikazu, Yoshitsuya, and Yoshifuji. With the sole exception of Yoshitoshi, the remainder followed the downhill path to the end of traditional ukiyo-e – more complicated compositions and flashy decorations of a horror vacui nature, replete with the abrasive colours created by the chemical aniline dyes imported from Germany.

Tsukioka Yoshitoshi was the lone exception. He and Kuniyoshi shared a deep taste for the macabre and the supernatural with Yoshitoshi following that direction, even in his early years; many of his prints were delicate and sublime, but most were not. His draftsmanship was superb, to the extent that the precision of the lines absolutely captured the emotions of the person or supernatural being depicted. Kuniyoshi himself was a great fan of his, but he could not have imagined where this direction would lead.

The Lonely House on Adachi Moor

In 1885, Yoshitoshi produced an iconic kakemono-e print entitled The Lonely House on Adachi Moor. It depicts a truly horrible subject, but it has been strongly sought after ever since because of the sheer quality of line and composition. The scene depicts the interior of a decrepit old farmhouse. A young woman is heavily pregnant, nude above the waist. She has been bound and gagged and suspended from the rafters by a rope tied to her ankles. Just in front of her, sitting on the floor is an ancient hag who stares intently at the terrorised woman as she sharpens a knife. The scene sums up the last stroke of genius of the last member of the Utamaro tradition. No gore is depicted, only that immediate time just before, the result of a brilliant and highly sophisticated artist. Both Yoshitoshi – and ukiyo-e – died on June the 9th, 1892.

This most excellent exhibition will make its point about Kunisada and Kuniyoshi and will rouse interest in the much wider world of classical Japanese prints. And the question as to who wins this competition will be left entirely up to the personal tastes of the viewer. If you’d like to vote, go to the museum’s website to take part.

BY MARTIN BARNES LORBER

Until 10 December, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, mfa.org. A catalogue by accompanies the exhibition, US$50