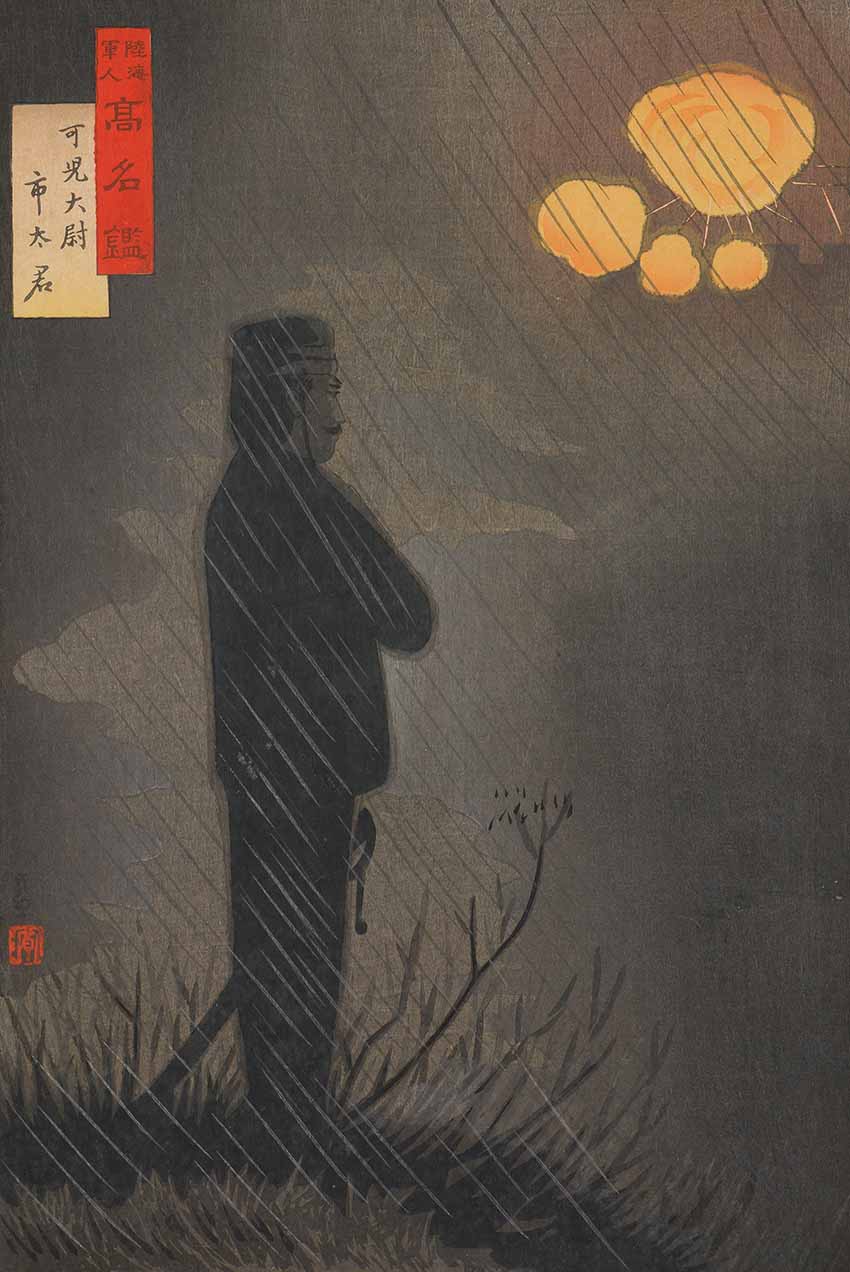

THIS AUTUMN, the St Louis Art Museum (SLAM) opens Conflicts of Interest: Art and War in Modern Japan, an unparalleled display of a range of Japanese art depicting and responding to the reality of warfare, featuring Japanese war prints.

The exhibition scrutinises the relationship between art and war through 180 objects: from woodblock prints to lithographs, postcards and even board-games. Curated by Philip Hu, associate curator-in-charge of Asian Art at SLAM, in collaboration with Rhiannon Paget, Andrew W Mellon Fellow for Japanese Art, the exhibition celebrates the gift of almost 1,400 pieces of Japanese art donated to the museum by Charles and Rosalyn Lowenhaupt.

The Troubled Meeting of Art and War

The troubled meeting of art and war is a fascinating subject, and one which continues to engender discussion. It was a pleasure, therefore, to have the opportunity to speak with Philip Hu about the exhibition, and delve a little deeper into the ideas communicated by the art and the catalogue. Our conversation spanned a remarkable breadth of topics, from the issues of curating work created during periods of conflict to the far-reaching influence of propaganda through art.

Lowenhaupts’ Collection of Japanese Military Prints

AAN: Perhaps we can start with a straightforward question about the Lowenhaupts, whose collection at the St Louis Art Museum has made it one of the largest public repositories of Japanese military prints. Could you tell us a little about them and their collection?

Philip Hu: Charles Lowenhaupt had been an exchange student during his high school period for a summer in Japan, so that was his first exposure to Japan. I believe it was in 1964 – that is the year that the Olympics went to Tokyo, although he was with a family on the outskirts of Osaka.

That was a very exciting period to be in Japan for a young person, because Japan was sort of ‘coming of age’ with the Olympics at the time. He got very interested in Japanese culture as a result of those first six months of exposure.

Mr Lowenhaupt and his wife, Rosalyn, have devoted many decades to putting this collection together. I believe they started collecting around 1983-1983 is quite an important year with regard to this kind of material. There are two reasons for this. One reason is because in 1983 the Philadelphia Museum of Art put on a small exhibition called Impressions of the Front, which featured Japanese prints from the Sino-Japanese War.

Japanese Prints of the Sino-Japanese War

It was a small exhibition, but it really was the first time that this material was shown to the public in the West in a concrete way. Also in 1983 was the publication of a book by Nathan Chaikin on the prints of the Sino-Japanese War (The Sino Japanese War (1894-1895) – The Noted Basil Hall Chamberlain Collection and a Private Collection).

These two things really triggered Mr Lowenhaupt’s interest: he began collecting and could not stop! He focused very much on military prints, which is great because very few people were paying attention to this genre during this period in the 1980s and 1990s.

A lot of people were still collecting classical Japanese prints of beauties, and actors, and landscapes – the more typical subjects that one might think about putting together in a collection of Japanese prints. He zoomed in on an area that was not popular, and so there was an abundant inventory of this material that he could snap up quickly and easily. In a way, it was very shrewd and thoughtful: how one would build a collection that is distinctive from most other collections of Japanese prints in the world.

AAN: May I ask you about the more general market history of these Japanese war prints? I was fascinated to learn in the catalogue about the British Museum’s (BM) acquisition of Sino-Japanese war prints, as early as 1895.

PH: As soon as they were made! Kudos to the BM.

AAN: In very general terms, what has the reception to these war prints been like over the years, both in Japan and abroad?

PH: During the time that they were first made, there was great interest in them; these pieces were being collected almost as soon as they were made, not only in the UK, but in France and Germany and even Russia. We know of very old collections that have been in these countries since the late 1890s.

They had a certain currency because many of these Japanese war prints were depicting the actual events that were happening in 1894 and 1895, during the Sino-Japanese War. And then a bit later – in 1904 and 1905 – they were depicting the Russo-Japanese War. The people who were collecting these prints probably found them interesting as a kind of journalism and current affairs.

The Russo-Japanese War

And then there was a big lull. The reason for this is because around the time of the Russo-Japanese War there began to be competition in Japan itself, and also in the West, from new technologies in visual production. Things were being produced by technologies such as lithography, both monochrome and colour lithography – sometimes called chromolithographs.

Photography was also coming up as a major medium in recording historical events, and any of these new materials were cheaper for the consumer to buy. So there was great competition between the traditional woodblock genre, which was a time-consuming method, and the much more machine-made and very fast production of printed materials.

As a result of that, these woodblock Japanese war prints began to decline in popularity in the 20th century. There were always people who collected these things, however, but they tended to be specialists, people who like Japanese woodblock prints as a material.

Japanese War Prints Declined in Popularity

Another reason why these prints fell into a lull is because of the way history unfolded, and as a result of natural disasters. In Japan, they had the Great Kanto Earthquake in 1923, which basically levelled Tokyo – many of these publishing houses were completely gone.

So were their stocks of these prints, with the earthquake and the fire. And then in the early 1940s, with the Allied bombing of Tokyo: the whole city was wiped out again. These two major historical events in 1923 and the early 1940s did these prints in, so to speak, just by eliminating their physicality from the face of the earth. So what has survived is all the more extraordinary.

Not just prints, but a lot of great art was lost in Tokyo itself, and elsewhere in Japan, with earthquakes and fires and tsunamis. Paintings and screens, and so on. Art in general is very fragile, and so it is the first thing to go. It is not the first thing you might think of carrying out when a fire engulfs your home.

AAN: You write very interestingly in the catalogue about the period of post-war pacifism having quite a severe impact on the popularity of these prints, and you describe how Japan and the rest of the world responded to art that depicts war. I was reading a piece by a contemporary art scholar named Mori Yoshitaka who called ‘the issue of war paintings… the biggest taboo in post-war Japanese art history’.

PH: For understandable reasons.The country had been through a terrible trauma, and the last thing anyone wanted to see was another image of war.

AAN: As a curator, you must have encountered issues of sensitivity, and I wondered how you have addressed them in your display of the artwork. Or is this no longer something that needs to be addressed?

PU: I think enough time has passed since these particular sets of prints were made. We are more than a 100 years beyond the end of the Russo-Japanese War, which ended in 1905. We now have very few, if any, living people who remember, or were involved in, those wars.

In a way, that makes it easier because the pain of seeing these things is not so severe. Even Japan itself has an understanding of these wars as historical events, and not necessarily as political events.

AAN: Has work like this been exhibited in Japan before?

PU: In my essay at the start of the catalogue I wrote about a number of small exhibitions that have been done in the West, as well as – very recently – a couple of exhibitions in Japan itself that have addressed this material. The Japanese are now realising that it is time to reflect on these works of art as works of art, but also to be able to understand them in the context of the country’s own history.

Are These Themes Consigned to History?

AAN: I wanted to ask about the timing of this exhibition. Can the work in this exhibition be read as a comment on, or reflection of, things going on globally at the moment? Or are its themes, as you say, completely consigned to history, and we therefore need not look for their relevance, in a political sense?

PH: In a very practical way, the exhibition and the catalogue were scheduled many years ago. This has been a project that has been in the making since 2010.

A large proportion of the Lowenhaupt collection was given to the museum in 2010, with the understanding that we would mount a major exhibition with an accompanying catalogue, so we have proceeded from that point as a matter of normal museum scheduling. In 2010, we could not possibly have predicted what historical events would happen in the world today.

In that sense, there is no connection at all between the timing of this exhibition and whatever is happening in the world. But that is not to say that there is no relevance, because I think this material is very relevant to what is happening today.

Unfortunately, war and conflict will probably continue to happen further down the road as well, so it doesn’t matter when this exhibition happens. I think the important thing is for the viewer of the exhibition and the reader of the catalogue to be given the chance to reflect upon history and conflicts.

But also my aim as a curator, and our aim as a museum, and the collector’s aim in collecting, was really to showcase the connection of art with war. That was the essential reason for doing this exhibition: to show how art made a major impression, using the subject of war.

These things were happening in Japan at this particular time in its modernisation, and the artists responded to that modernisation, and the consequences of that modernisation. These wars happened because Japan wanted to assert itself as a modern military power on the world stage.

Therefore the artists responded in the same way. Had Japanese history taken a different turn, we might have a very different kind of art from this period. It’s really a correlation between what the artists were seeing happening around them, and how they were expressing these events.

AAN: That ties in with something I have been reading recently, which refers to a very different time and a different medium, but addresses similar ideas: Susan Sontag writing on Don McCullin’s photography as a type of witnessing. She comments on the idea of moral coercion in McCullin’s photographs (‘A photograph can’t coerce’, she wrote in her essay Witnessing. ‘It won’t do the moral work for us. But it can start us on the way.’).

I wanted to ask you about this idea of moral coercion, and whether we can see any evidence of that in the work in this collection. Is there a clear agenda in this art, and does this agenda change over the years? Or is agenda too reductive a term?

PU: You are asking about the agendas within the art itself?

Is There an Agenda Behind the Creation of Japanese War Prints?

AAN: Yes: if there is an agenda behind their creation, or are these pieces simply acts of witness?

PH: Well, they are both. This body of material can be seen in a number of ways. It can be seen as historical reportage; the artists are trying to depict what they are hearing in the news and seeing in the telegraph reports coming into Tokyo daily.

Of course, it can also be interpreted as propaganda, although not as the official propaganda machine that we might think of. Many of these prints were produced by private publishers and were purchased by citizens, so it was not like the Japanese government was forcing these publishers to produce these prints or compelling these artists to make these images. The artists and publishers themselves were willing and able to do this without much government coercion at all. Part of it was also commercial.

If you read the essay in the catalogue by Andreas Marks on publishers of woodblock prints you will see that a lot of the impetus behind the creation of this material was a commercial one. They were simply trying to find new subjects to depict in woodblock prints so that they could sell them and make money. So there were commercial rather than political factors that drove the production of this subject matter.

What Distinguishes it from Straightforward Propaganda?

AAN: What I think also distinguishes it from straightforward propaganda is the use of satire, which I enjoyed reading about in the catalogue. To what extent are there humorous strands in this exhibition?

PU: We definitely wanted to feature satire as a major component of this material, which is why we invited Sonja Hotwagner – who is an Austrian scholar – to write one of the essays, and to help us with some of the catalogue entries on the satirical material.

In a way, satire is very difficult to translate, and she is the world’s expert on this material, so we are very glad that she could join our team and help tell some of the stories from this more humorous angle. You will see, if you read the catalogue, that there is not just Japanese satire: we have some examples of French postcards with satirical subjects, and in fact there are German, British and Russian satirical materials, too – we just do not have them in the collection. But they do exist.

AAN: Does the collection include manga?

PH: Not in the sense that we understand manga. The collectors were very focused on the body of material that we are presenting in this show. So they were not actually collecting manga as we know it. However, there is a very strong connection between the visual material in this show and catalogue and what later developed into manga. I think one can make that connection very easily.

AAN: We do not often think of wartime art as having a humorous edge, so it is intriguing to see this kind of work being exhibited.

PH: Yes, and we were glad to be able to present a couple of ‘light’ moments in the show as well. Otherwise, it is all very heavy.

AAN: You spoke about European postcards. I know that the St Louis Art Museum is exhibiting Goya’s print series Disasters of War (1810-1820) concurrently.

PH: Yes – it is on view already. It is a six-month long show, so a companion exhibition showing a Western example of how war was depicted by a very famous artist.

Can we make these connections between the art produced in wartime in the West and in Japan?

AAN: Which makes for an interesting comparison. Can we make these connections between the art produced in wartime in the West and in Japan, and are there any obvious exchanges that we should be looking at? Or are they quite distinct?

PH: The Goya set is very different. It is 19th century, so it is a bit earlier. And it is etching, so it is a very different medium. But the overtones are there: the sad outcomes of war, wounded people and shattered families. Some of these are general themes, which can be found in any war, not just these two.

The Goya set is there to provide a kind of reflective counterpart for people to see that there are some very common issues that are faced during wartime, and also that artists can approach these issues very differently, or they can approach them in many similar ways.

In addition to the Goya show, we are also about to open another exhibition on politics and propaganda in textiles. So we will have yet another companion show in a very different medium, but since we do have textiles in our show as well, it provides another level of reflection. These are things that people wore and used in their homes during wartime, with political subtexts.

Textiles Are Also Included in the Exhibition

AAN: I was surprised to see the textiles in the catalogue – and also the board games.

PH: That is another aspect of this material that not many people know about: the use of these materials to inculcate a very young audience on the home front. In fact, some of the young boys playing these board games in the 19th century and early 20th century, during these two wars, grew up to be the military leaders of Japan during the Second World War.

So we can see this early inculcation of military ideas, showing them what kind of jobs were available to them in the military, whether they wanted to be officers or join the navy – that these were seen as noble professions to pursue. Some of them were probably inspired to join the military academy. It is possible these people became who they were because of playing a game like this early on.

AAN: It is an interesting idea, but also quite an alarming one!

PH: Yes. Children absorb a lot of things, sometimes without our even knowing it.

AAN: When Conflicts of Interest is over, will some of the pieces be exhibited as part of the museum’s permanent collection, or do you intend for them to travel a bit?

PH: All the objects in the exhibition catalogue and the exhibition itself are part of the St Louis Art Museum’s permanent collection. At this point we are very open to having a couple more venues for the show, but not too many because this is primarily a works-on-paper show. For the long-term preservation of the material, we feel that maybe two additional venues would be our preferred maximum, otherwise we would be over-exposing these materials to light and too much travel. But if there were two fabulous venues, we would be very glad!

AAN: Do you have any favourite pieces that you feel visitors must not miss?

PH: Not just one – several! One of the wonderful things about this show is that it has many examples of these multi-panels. The normal format is the triptych, but we have got examples of four sheets, five sheets, six sheets. Nine sheets, even. When they are framed, they are actually very large objects.

It is quite a feat that they were able to design them so well that they could carry this narrative over a very long stretch of sheets. It is wonderful and rare to see. Very few museums or exhibitions will be able to show these kind of multi-panel prints. So that is one highlight. Another highlight you might see as you read the catalogue are these cut-out diorama prints. The prints were actually made to be cut out and assembled as three-dimensional dioramas.

AAN: I have never come across anything of its kind before.

PH: They are another aspect of these kinds of prints that very few people know about. We are pleased to be able to present them and help people understand that although these may be war prints they were also made in the form of games. They are actually not easy to put together! Ostensibly, they are meant for young people but they are very difficult to assemble.

I do also want to draw your attention to the very final print in the exhibition, which is the print showing Pearl Harbor. That is an extraordinary print for several reasons. It is a world-famous subject, but this particular print has never been published. It was printed on the first anniversary of Pearl Harbor; the actual attack was in December 1941, and this print was produced on the exact anniversary in 1942.

Another reason why this particular print is so important is because in the general history of Japanese woodblock printing, it is assumed that this kind of woodblock printing – ukiyo-e – came to an end after the Russo-Japanese War, in 1905. To have an example from 1942 blows that theory out of the water, and shows how the tradition of ukiyo-e, which was thought to have died out in 1905, still continued – albeit in much-reduced numbers – until at least 1942.

BY XENOBE PURVIS

From 16 October to 8 January 2017 at St Louis Art Museum, St Louis, www.slam.org.

Conflicts of Interest is accompanied by a catalogue of essays, edited by Hu, which features the work of scholars such as Sebastian Dobson, Sonja Hotwagner, Maki Kaneko and Andreas Marks. Themes raised by the exhibition and the catalogue will be further explored in a symposium of talks running from 21 to 22 October 2016 at the museum.