In the first decades of the 20th century, a new generation of print artists broke from existing traditions in Japanese printmaking to bring new energy to the traditional prints previously produced in Japan. By the end of the 19th century, the Japanese traditional print, ukiyo-e, had to face an unprecedented crisis. The cultural context of production was in the process of changing as prints were no longer being published, especially relating to the Yoshiwara district in old Edo (present-day Tokyo), a traditional ‘pleasure area’. The link between printmaking and daily theatre performances was also disappearing.

The Dawn of Sosaku Hanga

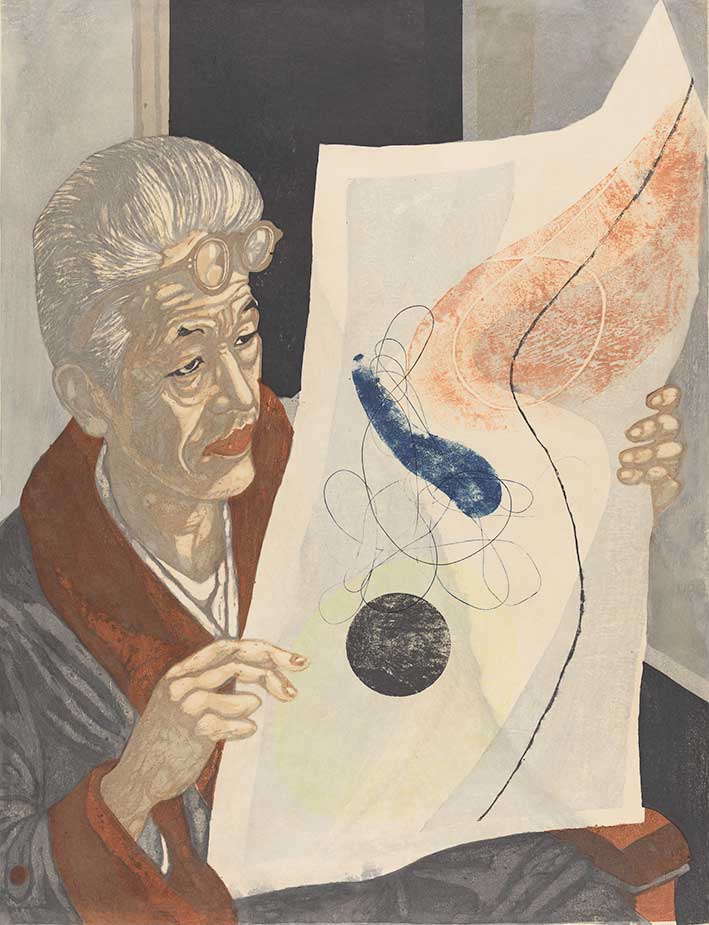

In the past, the labour of print production was historically divided among different craftspeople, but these ambitious artists sought to reinvent the medium by undertaking all aspects of a work’s creation, from designing and carving to printing themselves. This new approach to printmaking produced the sosaku hanga (creative print) movement, and the resulting artworks are often rough and unique to each artist’s developing techniques and abilities. Some of the most active practitioners of this new style joined the Ichimokukai, or First Thursday Society, organised by Onchi Koshiro (1891-1955), whose members met on the first Thursday of every month from 1937 until Onchi’s death. The artist was resolutely attached to the idea that an artist had to do the engravings themselves, including the plates. Onchi’s poignant portraits of women and urban landscapes position him as a pioneering abstract artist in Japan.

This sosaku hanga movement was inspired by Western practices and sought to enhance the status of engraving. The members of the sosaku hanga wanted to make the artist aware of all the stages in the realisation of their works, without the intervention of specialised craftsmen, such as the engraver or printer. Thus, the mark of the chisel on the block of wood became the expression of the artist’s personality, as did the brush stroke of the calligrapher, or brush strokes on paper. In comparison with shin hanga prints (new prints), the result is often more raw, imbued with a sense of spontaneity, impromptu, and unfinished. Unlike shin hanga prints, which attracted foreign buyers, sosaku hanga were mainly sold to a Japanese audience through subscription, or art exhibitions.

A striking print of a forest by Kitaoka Fumio is included in the exhibition. Originally enrolled in the Western oil-painting course at the Tokyo School of Fine Arts, he learnt the art of woodblock printing in his third and fourth years. Asked by Oliver Statler (1915-2002), the author and Japanese art expert, why he had stopped creating Western-style oils, he replied, ‘I like prints, too, because when they are made the Japanese way, with baren (printing tool) and handmade paper, they are a very Japanese art, and it is good to feel at home in one’s medium’. On his return to Japan from Manchuria in the late 1940s, he began selling prints after attending the meeting organised by Onchi. He went on to study engraving at the Ecole Nationale des Beaux-Arts in Paris and also taught in the US in the 1960s. By this time, his focus had switched, and he had settled to working in larger formats on gentle, evocative Japanese landscapes.

Hashimoto Oki’ie, born in Tottori prefecture, devoted much of his mature work to Japanese castles, and gardens, but in later life he also produced floral and figure subjects. Representing his work in this exhibition is a woodblock print, Misty Pond, created in 1966. Inagaki Tomo’o is best known for his many prints of cats, which gained him a wide following in the West. However, he only started producing them late in his career – as a member of sosaku hanga his prints for the first 30 years of his career covered a wide and typical subject matter for the movement, including many floral and still-life subjects, as well as landscapes and townscapes.

Sekino Jun’ichiro was a prolific artist during his early years with the sosaku hanga movement and was closely associated with Onchi. He also wrote about the print world, as well as being a book illustrator. After Onchi’s death, he developed his own style and achieved success with his prints of the kabuki and bunraku theatres; his interest in this world probably stemmed from his work during the Pacific War (part of the theatre of the Second World War) (1941-45), when it is believed that he was involved in arranging entertainments for troops, in particular tours by kabuki actors and bunraku troupes. He is also known for his portraits of artists such as Onchi and Munakata Shiko (1903-1975).

Artists in the exhibition include: Kawakami Sumio (1895-1972), Hashimoto Oki’ie (1899-1993), Hiratsuka Un’ichi (1895-1997), Inagaki Tomo’o (1902-1981), Kitaoka Fumio (1918-2007), Sekino Jun’ichiro (1914-1988), Shima Tamami (1937-1999), Shinagawa Takumi (1908-2009), and Iwami Reika (1927-2020).

Living through imperialist expansion, wartime scarcity and foreign occupation, these artists sought international recognition for works that captured their individualism and self-expression amid a changing world. The Print Generation offers a selection of creative prints that challenged the dominant narrative of what it meant to be an artist in 20th-century Japan. Highlights from the Kenneth and Kiyo Hitch Collection and the Gerhard Pulverer Collection illustrate the development and evolution of the sosaku hanga movement as well as the international reach of these artists and the depth of their relationships to each other.

From 16 November to 27 April, 2025, National Museum of Asian Art, Sackler Gallery, asia.si.edu