A notable new development in the decorative arts was first seen with the emergence of the Rinpa School. The school was based on an informal lineage of painters from the founding of the movement by Hon’ami Koetsu (1558-1637) and Tawaraya Sotatsu (dates unknown). The name for this movement comes from the second character of the family name of Ogata Korin (1658-1716), who is considered the leading exemplar of the Rinpa school of decorative art with the school later named after him (Korin plus ‘ha’: ‘school of’).

Currently, the Honolulu Museum of Art is showing a number of works by some of the best artists from this Rinpa movement. Perhaps the most dynamic effect of the establishment of the Tokugawa shogunate in Edo (now Tokyo) at the beginning of the 17th century was economic prosperity and an energetic renaissance of traditional arts. Coincidental too was the emergence of a new, urban culture as tradesmen and craftsmen catered to a booming market for luxury goods, while a city milieu of kabuki, sumo and the pleasure quarters, evolved for entertainment.

Before long, the old, Eastern Imperial capital of Kyoto and the new, Western political capital of Edo developed their own completely different flavour and character; that of Kyoto being infused with the refined style of courtiers, tea masters and temple clerics, while Edo culture was brasher, more mercantile – and was probably a lot more fun.

Rinpa Art

Rinpa art is usually associated more with Kyoto, its nobles and élite craftsmen, along with an artistic tradition influenced by courtly, poetic ideals, together with the practice of Zen and the tea ceremony. All were much inspired by the area’s rich nature. The sober, monochrome aesthetics of the tea ceremony had almost a monopoly on taste through the 15th and 16th centuries and it is as if in defiance of this – as well as to celebrate the new political stability and affluence – that extraordinarily talented artists and craftsmen began to explore a freer, more exciting use of colours, pattern and form.

Foremost among these were followers of the Rinpa school that has continued in a recognisable form into the modern world and our contemporary era. While other formal schools were more regimented with a teacher/pupil system for the lineage of artists, the Rinpa school was less regulated and did not have a continuous teacher/pupil system in place. Many artists mastered the style through their own independent study and observance of existing works and not through direct pupillage. Artists also expanded their practice to encompass lacquerware, ceramics, and textile design.

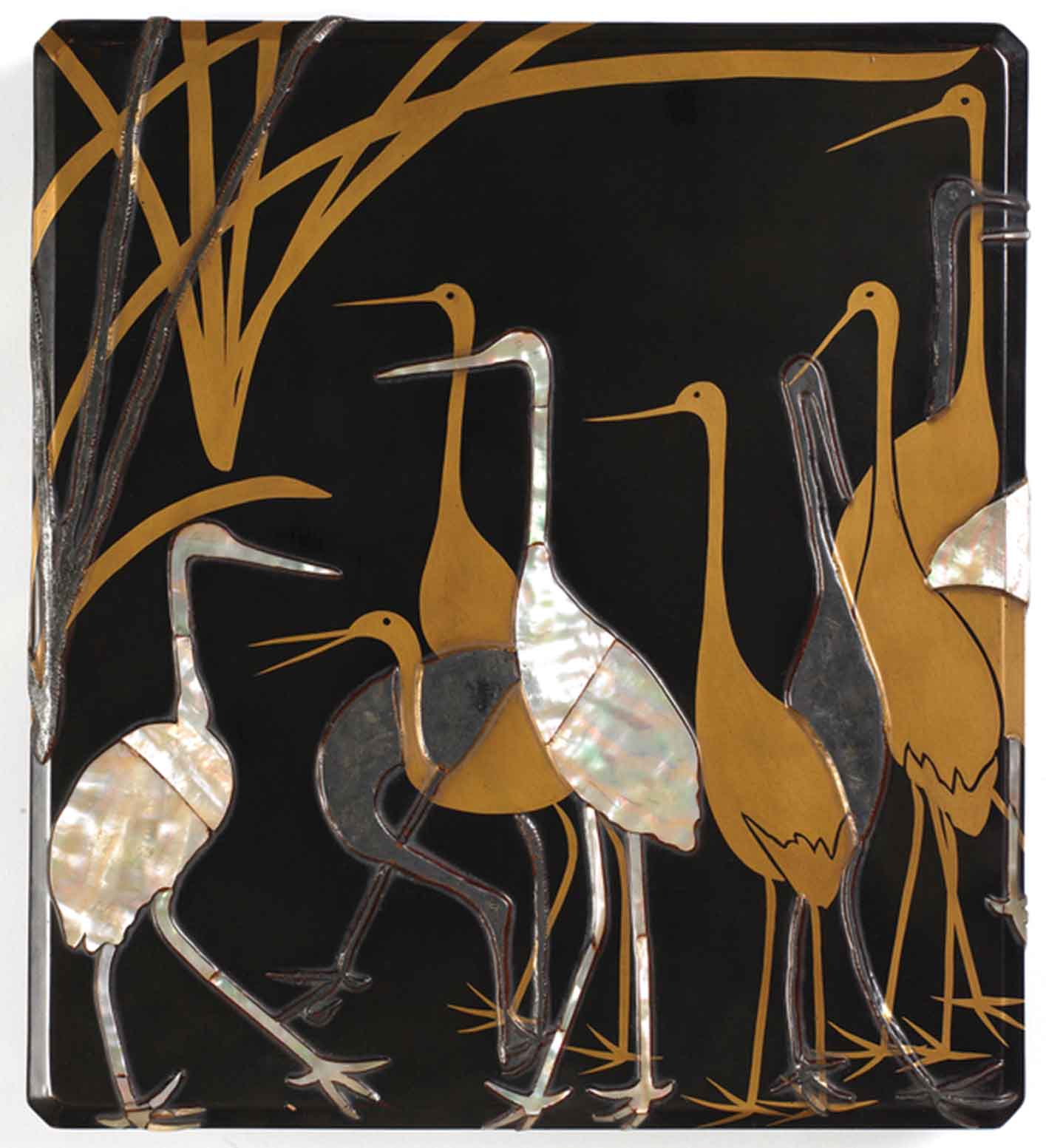

Characteristic of Rinpa art is a dramatic sense of design and pattern, unusual techniques of painting, and a flair for exciting composition. Drawn outlines were often ignored, and tarashikomi – the application of ink or pigment to pool on wet paper – was a chosen method for shading or colouring. Gold or silver was often used in leaf-form as background, or as a finely ground dust mixed with liquid agent for painting, and, as clients for Rinpa works tended to be well-heeled, both materials and pigments were usually of the best quality.

Hon’ami Koetsu

Hon’ami Koetsu (1558-1637) and Tawaraya Sotatsu were two of the earliest artists whose works demonstrated this new style. Koetsu came from a family of sword-polishers and appraisers and become renowned as a master-calligrapher, as well as a designer of gardens, ceramics, and lacquer objects. Existent works show how the two often collaborated, where Sotatsu had prepared a painted scene in gold or silver, over which Koetsu brushed verses in his characteristic, free-style calligraphy. Koetsu excelled at everything he tried, perhaps this is best seen in his calligraphy, as he was named one of the Kane’ei sampitsu, or ‘Three Brushes of the Kan’ei Era’. The culture to which Koetsu and his contemporaries admired was the classical ‘golden age’ of the Heian period (794-1185), the time of the Tale of Ise and Tale of Genji.

Various examples of hand-scrolls and poem-cards feature painted seasonal subjects such as deer, vines, bamboo and flocks of cranes, and even though beautiful they must have been in their original form, a new artistic level altogether is attained by the addition of calligraphy. Such layers of suggestion, hints and nuances are characteristic of Rinpa art.

While mainly remembered for his calligraphy, Koetsu was above all a designer like most of his Rinpa followers, drawing no border between various forms of artistic expression, and in all likelihood acting as an adviser to subordinate craftsmen much as designers do today. His low-fired raku ware tea ceramics are still highly admired and an example of one of the artist’s teabowls can be seen in this exhibition .

While the Rinpa artists had no enforced limits to their artistic expression, they all seemed bound by an awareness of the refined taste that is associated with Kyoto – a taste for colour, line, texture and form that is recognisable to our present-day eyes and harmonises with our modern aesthetic ideals.Also inspired by the monumental painting of the Momoyama period (1573-1615), Rinpa painters turned their hands to making large screen-paintings with a gold or silver background that were used for delineating space in grand households and castles.

Ogata Korin

Nature has always provided a wealth of inspiration for writers and artists and the Rinpa artists made spectacular screens showing trees, grasses and flowers painted in compositions that demonstrate their strong sense of design. Internationally celebrated – and now almost one of the icons that come to mind when one thinks of Japan – are the famous iris screens by Ogata Korin, normally displayed at the Nezu Museum and designated a National Treasure of Japan. The centrepiece of Japanese Design: Rinpa in Honolulu is a unique screen with white chrysanthemums on gold painted by Korin on one side and red maple leaves on silver painted by Hoitsu on the other, which allows the viewer the rare opportunity to compare the hands of these masters from different lifetimes side by side.

Another aspect of Rinpa art is the juxtaposition of realism and stylisation that can be startling, but also inspired and successful. Korin’s brother, Ogata Kenzan (1663-1743) is celebrated as an artist who explored the design possibilities of Rinpa painting on the three-dimensional, often curved surfaces of ceramics. Until Korin’s death, the two brothers often collaborated, with Korin painting the ceramic works made by Kenzan. These works, (and those made exclusively by Kenzan), demonstrate the Rinpa artists’ understanding of the possibilities and limitation of three-dimensional designs and how they calculated them to look interesting from all angles.

By the early 19th century, new ideas and developments in the Rinpa style were mainly seen in Edo rather than Kyoto. The painter Suzuki Hiitsu (1796-1858) was one such prolific and influential artist working in Edo during this time. Examples of his work in the exhibition include a pair of hanging scrolls of Morning Glories and Gourds.

The precept that painterly techniques can be adapted to all media, as espoused by past Rinpa masters, has continued to make the Rinpa style not only popular with modern audiences, but still influences contemporary design today.

Until 9 October, 2022, Honolulu Museum of Art, honolulumuseum.org