Arguably, a thoroughly unexpected celebrity became entranced by Japanese cloisonné – Rudyard Kipling. He describes his reaction to seeing the cloisonné process like this: ‘It is one thing to read of cloisonné making, but quite another to watch it being made.

‘I began to understand the cost of the ware when I saw a man working out a pattern of sprigs and butterflies on a plate about ten inches in diameter. With finest silver ribbon wire, set on edge, less than the sixteenth of an inch high, he followed the curves of the drawing at his side, pinching the wire into tendrils and the serrated outlines of leaves with infinite patience … Followed the colouring, which was done by little boys in spectacles.

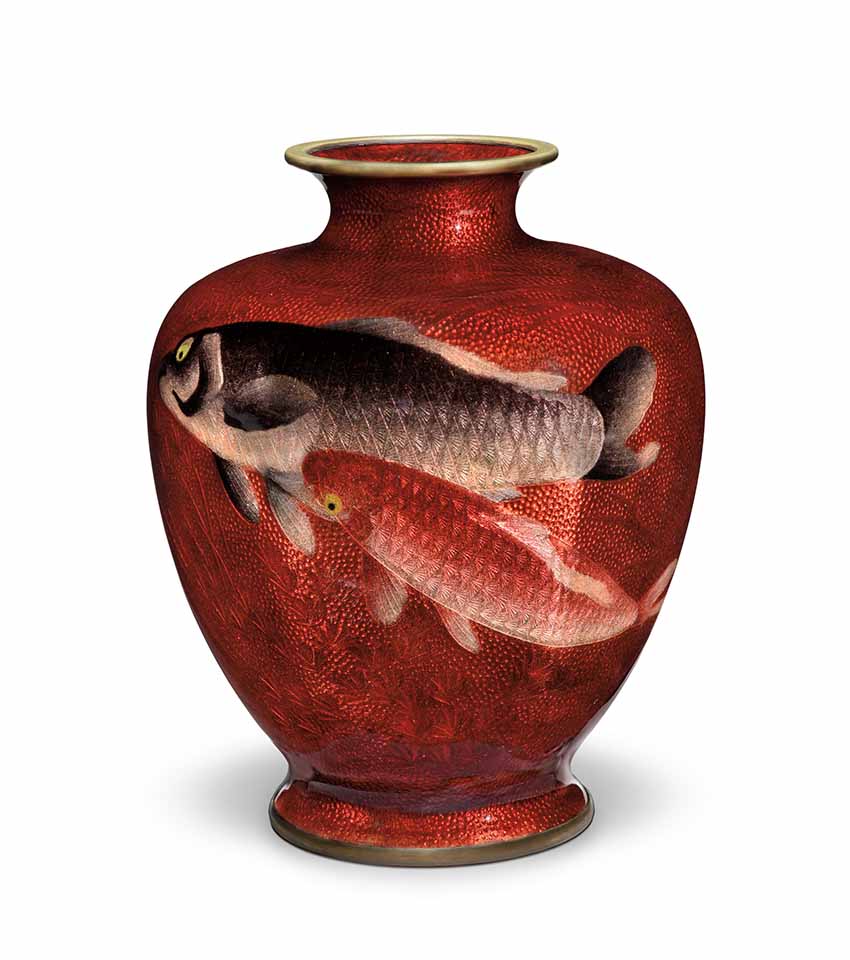

‘With a pair of tiniest steel chopsticks they filled from bowls at their sides each compartment of the pattern with its proper hue of paste … I saw a man who had only been a month over the polishing of one little vase five inches high. He would go on for two months. When I am in America he will be rubbing still, and the ruby-coloured dragon that romped on a field of lazuli, each tiny scale and whisker a separate compartment of enamel, will be growing more lovely.’ Kipling wrote this in Sea to Sea & Other Sketches, Letters of Travel published in 1889.

The History of Japanese Cloisonné

Polished to Perfection is the abbreviated title of an exhibition at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) focusing on the ‘Golden Age’ of Japanese cloisonné enamelware (around 1880 to 1910). From tentative beginnings in the 1830s in Nagoya, by the first decade of the 20th century cloisonné production had bloomed into one of Japan’s most successful forms of manufacture and export.

During this Golden Age it achieved not only a peak of creative and technical sophistication, but also a pinnacle of exquisitely delicate beauty. Becoming internationally famous, it was displayed at the world exhibitions of the era. It was artistically influential too, giving birth, amongst other media, to the passion for Japonism, that craze for Japanese art and design in the West.

Golden Age of Cloisonné Production in Japan

During the Golden Age of cloisonné production four great masters of the genre emerged: Kawade Shibataro (1856-1921), Namikawa Yasuyuki (1845-1927), Namikawa Sosuke (1847-1919) and Hayashi Kodenji (1832-1915). These and other exponents of the renaissance of Japanese cloisonné are represented by approximately 150 works in the LACMA exhibition, taken from the Collection of Donald K Gerber and Sueann E Sherry.

This collection, built over the course of more than four decades, is of museum quality, and works in the collection are either gifted or promised gifts to LACMA. It represents the Golden Age characteristics of both intricate or minimal surface design; a highly sophisticated and often memorably translucent use of colour; expanded varieties of form, for instance into ground-breaking three-dimensional vessels; different enamelling styles and materials for the wires separating the cloisons (the French word for ‘areas’); and the flawless, ‘polished to perfection’ surfaces lauded by Rudyard Kipling.

The Catalogue

In the associated catalogue for the exhibition, Michael Govan, CEO and Director of LACMA, alludes to the immense variation in style and finish of Japanese art: ‘While some of the finest works are rough-hewn, visibly handmade objects revered for their imperfection, others are immaculate, intricate pieces whose making seems almost impossible to comprehend.

The art form that has long been Donald Gerber’s passion is a prime example of the latter type of Japanese art: cloisonné works, made through a painstaking process that involves the application of wire and enamel to copper cores, displaying a preternatural polish. Donald has spent his life gathering together the finest cloisonné specimens, and his and Sueann’s remarkable collection includes masterworks by virtuosos of the form’.

Passion for Cloisonné

Donald K Gerber describes in his introduction to this luminous enamelware, ‘Some 45 years ago, in a little Kyoto studio called Inaba, I was introduced to a type of art that would become the centrepiece of my life. My first encounter with Japanese cloisonné enamels was a revelation; for me, looking at a piece of cloisonné was more like looking into it andseeing a magical, mystical, miniature world of nature.

‘My deep interest in Japanese cloisonné has led me on a nearly 50-year journey across the country and around the world to meet fascinating people and examine exquisite art. It has been physical, intellectual and spiritual. I have hunted down cloisonné objects, studied the history of this unique art form, and been moved by the beauty of each piece I have found along the way.

‘Over the decades, my collecting has evolved. Like a Bonsai tree, the Gerber/Sherry collection has been planted, pruned, and finely manicured – or, indeed, like cloisonné itself, which is created through a laborious process that includes decorating, firing and polishing, the collection has been “polished to perfection”. And the journey is still going on’.

Shippo

Shippo, the Japanese word for enamelware, is composed of characters translating as ‘Seven Treasures’. This is a reference to the seven treasures mentioned in Buddhist texts, which include substances of vivid colour such as emerald, coral, lapis lazuli and gold. Chinese cloisonné enamels had long been admired and highly valued by the Japanese, who applied the term shippo to the rich colours of Chinese production, and later to cloisonné objects made by their own craftspeople.

Early Examples

There are few early examples of Japanese cloisonné apart from architectural details such as small door fittings with enamelled designs in the Phoenix Hall (1053) of the Byodoin Temple near Kyoto, and cloisonné enamel-decorated details used for the Higashiyama retreat of the shogun Ashikaya Yoshimasa (1436-90) in eastern Kyoto.

A gilded bronze door-pull (hikite) with cloisonné enamel decoration, dated circa 1700, is in the collection of the V&A, London. But this hikite pales in stylistic and technical comparison to the cloisonné of the later Golden Age. Otherwise, prior to that resplendent era, enamelling in Japan was also used for decorative nail covers (kugi-kakushi), and water-droppers (suiteki), which were part of writing sets.

Enamel Techniques in Sword Fittings

However, the samurai had for centuries commissioned fine decoration for the fittings of their swords, in particular the sword-guards (tsuba), which were often works of art in their own right. The Hirata School, productive well into the 19th century, was famous for the most coveted of these sword fittings.

It was a former samurai, Kaji Tsunekichi (1803-1883) from Nagoya in Owari Province, who is credited with the renaissance of Japanese cloisonné manufacture, in fact the birth of the dazzling products of the Golden Age. This more or less coincided with the Meiji period (1868-1912), during which time there was a growing emphasis on decorative crafts. After more than 200 years of isolationism, Japan was opening up to contact with the West and modernising under a new emperor, that ‘opening’ prompted by facing Western cannons.

The Rise of Cloisonné Making in Meiji Japan

As part of this modernisation, samurai like Kaji Tsunekichi were banned from carrying swords, and gravitated from their feudal military role to a more bureaucratic one. Like so many other samurai, Tsunekichi was forced to find methods of supplementing his meagre official stipend. The story goes that around 1838, he took apart a piece of Chinese cloisonné enamel, examining how it was made, and managed to produce a small cloisonné enamel dish. It was not until the mid 1850s that this enterprising samurai felt sufficiently confident about his enamelling skill, that he took on pupils. By the close of that decade he was appointed official cloisonné-maker to the regional warlord of Owari Province.

Having originally dissected that item of Chinese cloisonné, Tsunekichi’s early work was markedly influenced by Chinese design, on which he based his motifs and colours. In a decorative manner, he used a large number of background wires as an integral part of his design. This also had a practical function, in that it prevented the enamels from running during firing. Later masters were able to reduce the number of wires.

The Maker Tsukamoto Kaisuke

Hayashi Shogoro (d 1896) was one of Tsunekischi’s students, most celebrated for the fact that his pupils in turn became teachers of the early masters of 19th-century cloisonné, in particular Tsukamoto Kaisuke (1828-1887). Around 1868, Kaisuke is credited with developing the technique of applying cloisonné enamels to a ceramic vessel, and some fine examples resulted. However, copper cores later replaced ceramic, since enamels on porcelain emerged as somewhat dull and grubby looking, also liable to crack.

Nagoya Cloisonné Company

Kaisuke’s star student was Hayashi Kodenji (1831-1915), who subsequently trained other cloisonné makers. Kodenji was one of the most influential exponents of the art and opened an important workshop in 1862 in Nagoya. Many cloisonné manufacturing companies were established in and around Toshima, including the Nagoya Cloisonné Company. In 1873, the products of their technological advances and of course their artistry won the company a First Prize at the Vienna Exhibition. Toshima became known as Shippo-cho (cloisonné town), having become Japan’s main centre of production. At its peak it’s been estimated that the cloisonné workshop/factories there were responsible for 70% of the production in Japan.

By the 1870s, Japan’s open-door policy to the outside world, in particular to the West, resulted not only in the enthusiasm for Japonism, but in a two-way creative and technical stimulus. Influenced by exposure to Western art and technology, cloisonné makers were incorporating and inventing new techniques. Cloisonné production soared.

Gottfried Wagener and Enamel Making

By 1875 Tokyo was becoming important on the Japanese arts scene, to which Tsukamoto Kaisuke moved, becoming chief foreman of the Ahrens Company. Under the Meiji government’s programme of modernising Japan’s industries, Western specialists were invited to contribute. One such was a German chemist named Gottfried Wagener (1831-1892), who played an important role in introducing modern European enamelling technology to Japan. As the curator of the LACMA exhibition, Robert T Singer, points out: ‘Wagener’s advanced methods allowed artists to fashion areas of cloisonné with less and less wirework to hold the melted enamels together and to separate them from one another’.

Namikawa Yasuyuki Cloisonné Artist

Wagener moved to Kyoto in 1878, meeting Namikawa Yasuyuki (1845-1927), a former samurai and important cloisonné artist. The collaboration between the two had significant results, one of which was the creation of lyrical translucent mirror-black enamel. Another hallmark was his use of silver and gold wire, gradually replacing the traditional copper material. In 1896 Yasuyuki was appointed Teishitu Gigel (Imperial Craftsman) to the court of the Emperor Meiji.

Robert T Singer devotes an entire chapter to Yasuyuki in the catalogue of the exhibition (to the exclusion of all other cloisonné artists). He titles it: ‘Growing More Lovely, The Seductive Beauty of Namikawa Yasuyuki’, and describes Yasuyuki as ‘the most celebrated cloisonné artist in history.’ By happy chance, Singer lived for a while in the estate of the artist and takes the reader on a typical tour led by Yasuyuki for guests such as Rudyard Kipling. He would begin with the Meiji-style garden to introduce his guests to aspects of Japanese aesthetics, thereby preparing them for ‘his artworks, which are distillations of Japanese nature motifs – primarily birds and flowers.’

Early Pieces

Some of these were early pieces, with stylised designs referring to textile motifs (meibutsu-gire), in some cases derived from Chinese designs. Though other early pieces were traditional, mainly of stylised botanical motifs, to which Singer is referring, later work tends more to the pictorial with natural scenes and views of landmarks in and around Kyoto. Singer adds that later the shapes of the vessels become larger and more varied in form, and the imagery closer to classical Japanese painting in design and conception.

Singer continues his description of Namikawa Yasuyuki’s tour with the artist’s display to his guests of various stages of cloisonné making, with a ‘process set’ of six samples of the ‘extremely laborious method: first, the brushing of contour lines in ink on the copper core, the filling in of ground glass between these wires, the firing of the piece in a remarkably primitive kiln, the repetition of those stages over and over, and then the protracted process of 14 stages of polishing.

‘The polishing process is not a trivial endeavour’, continues Singer, as Kipling has described after visiting the estate. ‘Visitors … would also be shown a wooden box in which 14 polishing-stone samples were … arranged from roughest to smoothest’.

At the end of the tour, naturally enough, Yasuyuki ‘would carefully and slowly lift out of its box, and unwrap from its silk brocades, one of his precious creations. Only a few pieces would be shown, providing the visitor with a small selection from which to choose a purchase. Even in Namikawa’s lifetime, his enamels were exceedingly valuable, easily fetching ten pounds or more – then a considerable sum’.

In March 2013, at a Christie’s auction in New York, a pair of cloisonné enamel vases by Kawade Shibataro sold for US$111,750. Christie’s lot essay describes these vases as a fascinating ‘interplay between natural motifs and abstraction that characterises Art Nouveau.’ And very typical of that movement they look. The essay further elaborates how the opening-up of Japan to the West was reflected in Shibataro’s work. He ‘encountered a range of enamel work trends and techniques on his international tours representing Japan in world expositions in Europe and the United States, beginning with the 1885 show in Nuremberg, where he earned a silver medal’. The essay goes on to describe other international awards such as at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893 (held to celebrate the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus’ arrival in the New World), a bronze medal in St Louis in 1904, and participation in Liège, in 1905, at another exposition. Cloisonné was really going global, though Shibataro also entered his work in domestic fairs.

He introduced and developed many technical innovations, one of the most important of which was morriage shippo (piling up enamel). This was a painstakingly laborious technique in which he was unrivalled, involving building up layers of enamel which produced an incredibly delicate three-dimensional effect. The subsequent subtle lustre was ideally suited to the background for flowers and other plants.

Shibataro is also celebrated for other remarkable innovative techniques, such as repoussé and drip-glaze (nagare gusuri), which replicates the effect of flambé and ash ceramic glazes. Inspired by aspects of Japanese painting, he developed relief decoration and plique-à-jour, (shotai-jippo). Another leading cloisonné artist, Ando Jubei, had seen examples of this at the Paris Exposition of 1900, bringing back a piece by Fernand Thesmar. Shibataro analysed the technique, further developing it. As a document on cloisonné produced by the V&A, which owns a splendid collection, explains: ‘In shotai-jippo an object is prepared as for cloisonné enamelling, though with the wires fixed only by glue. The interior is not enamelled and once the piece has been completed, clear lacquer is applied to its polished exterior to protect it from the acid which is used to dissolve the copper body. The resulting fragile object consists of semi-transparent panels of enamel held together by a pattern of fine wires.’

During the 1880s, Shibataro simultaneously ran his own workshop in Nagoya, and worked as a subcontractor for the Ando Company. Its foreman from 1881 to 1897 was Kaji Sataro, the grandson of Kaji Tsunekichi, the former samurai who had kick-started the renaissance of cloisonné production by taking apart the Chinese example. After participating in the Exposition Universelle of Paris in 1900, Kawade Shibataro headed up the Ando Cloisonné Company from 1902-1910. As Christie’s essay comments: ‘The Paris exhibition was a unique window into the cross-fertilisation of modern art accomplished through the international fairs, astonishing Japanese artists with the embrace of Japanese design by their Western counterparts and visa-versa.’ Thus the clear Art Nouveau reference in the glorious Shibataro peacock feathered vases on their turquoise grounds.

Ando Jubei (1876-1953), who was also known as Jusaburo, was orphaned at less than one year old. According to his father’s will, he was brought up by employees of the Ando Company. Jubei’s sister married one of the founders, and together Jubei and his brother-in-law, Ando Juzaemon, ensured the cloisonné company’s success. Juzaemon travelled to Chicago in 1893 for the World’s Columbian Exposition, and Jubei went to the International Exhibition in Glasgow, where he stayed for two years to study the art market. Some of the cloisonné exhibited in Chicago demonstrated that the cloisons, the areas bounded by wires attached to the base metal to keep the ground glass in place as it melted or vitrified in the kiln, could be dispensed with altogether.

After their return to Japan, they invited Kawade Shibataro to join them. Cloisonné production soared to new heights of unparalleled artistic and technical perfection, as well as sales. The Ando Company won many prizes at world exhibitions, and by 1918 at least 50 artists worked for the Company, which was given an Imperial Warrant of Appointment to the Japanese court. Its products were presented as diplomatic gifts. It is unique in the sense that it is the only manufacturer with its roots in the Golden Age still producing high quality cloisonné enamel.

Yet another former samurai, Inaba Isshin, who had begun working with enamels in 1875, founded the Inaba Company of Kyoto, in 1886, mentioned by the collector Donald K. Gerber as the place where he first encountered the ‘revelation’ of Japanese cloisonné. The company’s achievements were eclectic, combining designs and techniques from both Kyoto and Nagoya, and continued production until the 1990s.

Other cloisonné artists were emerging in the latter part of the Golden Age, younger ones such as Kumeno Teitaro (1863-1939), six of whose lyrical works are part of the collection in the exhibition, including a glorious pair of tall yellow vases on which are painted dragonflies and flowers. He was particularly celebrated as the perfector of tsuki-jippo (also known as tomei), a technique in which transparent enamel is applied over relief designs in gold or silver. Furthermore, he excelled in the exceedingly challenging method called shotai-jippo or plique-à-jour, in which the supporting metal is removed after firing, leaving the glass and the wires supporting themselves.

Namikawa Sosuke (1847-1910), whose luminous masterpieces are also illustrated in the catalogue, created works with shimmering, pale pastel backgrounds, of breathtaking beauty and subtle simplicity. His trays have glowing mounts of an alloy of copper and gold (shakudo) which surround a heart-stoppingly beautiful heart-shaped tray depicting a gentle mountainous landscape surmounted by a full moon. The colour palette is restricted to pale beige-grey, highlighted with white blossom. Another similarly minimally coloured rectangular tray features a drooping branch of white cherry blossom, with the moon emerging from soft bands of clouds in shades of pale grey.

In the catalogue for the exhibition, John R Wilson comments how cloisonné companies and individual artists benefitted from the Japanese government’s intensive promotion of its art and crafts, achieving considerable commercial success, especially as Western powers had imposed provisions to open certain Japanese ports to foreign trade. Thus Japanese commodities fared well on the Western art market, some influential art critics becoming effusive in their praise of Japanese art. One of these, from the Japan Weekly Mail, commented: ‘Japan has made such strides that her enamels have left their Chinese predecessors at an immeasurable distance and stand easily at the head of everything of the kind the world has ever seen’.

BY JULIET HIGHET

Until 4 February, at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), Los Angeles, lacma.org. A catalogue accompanies the exhibition, ISBN 9783791356143