Confucius on Jade said: ‘The gentlemen scholars of antiquity all enjoyed the extraordinary qualities found in jade: warmth, smoothness, and a certain gloss, it had a benevolent and good character, as it is considered fine, compact, yet strong, like a man’s intelligence. When struck, it yields a note clear and prolonged, and yet it terminates abruptly, like music. Its flaws do not conceal its beauty, nor its beauty conceal its flaws, like loyalty it is esteemed by all under the sky, like the path of truth and duty’. This adapted quotation from Confucius encapsulates the many qualities of jade.

The Passion for Jade in Asia

The exhibition at the Guimet National Museum of Asian Art (MNAAG), in Paris, aims to trace the development of jade in China and the widespread passion it aroused throughout Asia and far into the Islamic world. And then later in the creative years of the Art Deco period in Paris, as well as among American tycoons and lovers of high jewellery inspired by how jade is used in decoration in China.

The exhibition has unprecedented loans of great masterpieces of jade carving from the National Palace Museum (NPM) in Taipei. This prestigious institution has in its collection some of the greatest works of art from Chinese Imperial collections. The NPM and MNAAG have been carefully developing their scientific and cultural partnership for years.

Guimet Museum’s Collection of Jade

To celebrate this partnership, the exhibition was created to bring these very important and glorious loans to Paris to show alongside the Guimet’s collection of jade, which is especially strong in archaic jades, bequeathed by Dr Gieseler in 1932.

Loans from other French institutions are also included – there is an exceptional loan from the musée chinois de l’Impératrice Eugénie in Fontainebleau. Other major institutions that have lent masterpieces from their collections include musée du Louvre, muséum d’histoire naturelle, musée Jacquemart André, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, musée Cernuschi and Cartier. The result is an overall landscape of an Asian and imperial jade – which has been a royal passion, not just in China, for centuries.

From the Earliest of Times

From the earliest times, jade has enthralled people across the continents of Europe and Asia. From the 6th to the 4th millennia BC, Neolithic cultures carved and polished jade to make large axes and circular discs, scattered in archaeological sites from the steppes of Mongolia to the westernmost part of Europe. Jade objects (axes and disks) lent by the musée de Vanne (Brittany, France) are presented along with similar Chinese pieces from musée Cernuschi.

Tools Used to Carve Jade

Tools used to carve and to polish this stone are displayed at the beginning of the exhibition with objects of different form, function, and period to show the diversity of colours of the stone. It varies from pure white to a dark green almost black, from russet to palest mauve.

The beauty of jade is never a given quality, whether it is in its nuances of its colours, its transparency, or its opacity. It beauty is revealed through a painstaking process of carving and polishing to show the latent form, motif and colour it encloses. The carver will reveal a design by playing on the veins and colours. Boulders of russet jade had been frequently used to create shanzi miniature mountains clad in autumn colours.

The exhibition, unusually, is not in chronological order. It begins with the reigns of Yongzheng and Qianlong emperors to show how a classical and thorough knowledge of the long history of Chinese jade was organised and used to create new masterpieces during this period.

The Ritual Use of Jade

This first gallery explores the usage of jade in the ritual of Celestial bureaucracy, with a highlight being a very important casket and book of jade that commemorates the Fengshan, an important sacraficial ritual to Heaven and Earth completed by Emperor Zhenzong (r 997-1022) on Mount Tai.

This use of jade embodies the communion between the ancestors and the spirits of Heaven and Earth. Other such ritual objects are covered by loans from Bibliothèque National de France, the MNAAG, and the NMP that show how inscribed jade is used in the quest for eternity.

Literati Taste

The next section covers literati taste and connoisseurship in Chinese antiquities from the Song dynasty until the end of the Qing, with a special focus on the 18th century. An elegant jade tree and rocks are displayed alongside a camphor woodblock print in order to connect these various works of art and to explain to the audience the context and formation of literati taste.

A bear-shaped vase from NPM is displayed alongside a bronze bear from the Western Han dynasty and a copy of the Archives of the Office of Workshops in the Imperial Household, which acknowledges the creation of the ‘revival’ jade bear by an imperial court artist in 1760. ‘Taking the antique as a master’ is a key phrase to understand the art of jade, especially in connection with the long and fruitful reign of Qianlong.

A Collection of Important Archaic Jades

The second gallery presents a large collection of important archaic jades from very early Neolithic cultures up to the Han dynasty. Some pieces from the Qija culture, collected by various emperors and reworked during their reign, are included in the show.

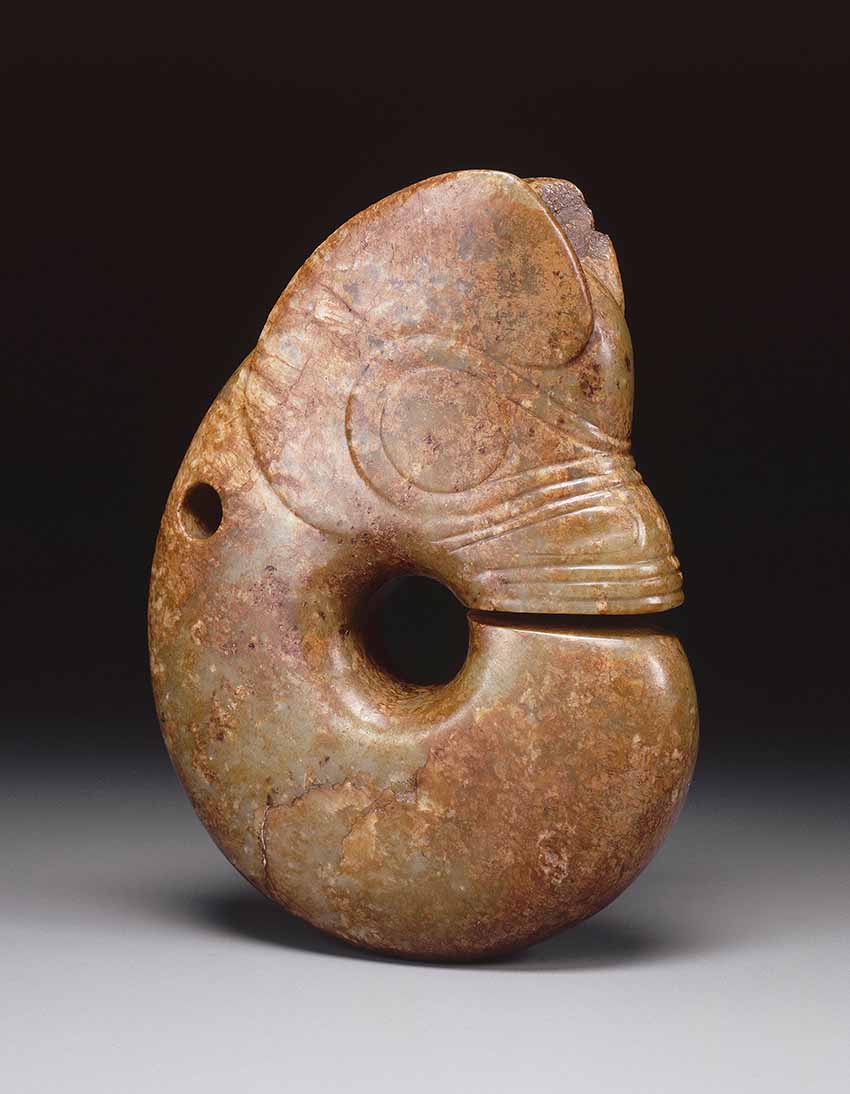

Pure forms are displayed in a spectacular showcase that displays these elementary and iconic objects from such remote times: bi, huang, and fu (axes), yazhang, ceremonial blades, ve dagger, and cong. Also included are the intriguing bestiary of zhulong, pig-dragon, kui, bear, dragon, tiger and ornamental jade engraved with a fascinating range of motifs, as well as openwork discs with bird decoration.

Often Considered More Precious Than Gold

Jade is often considered more precious than gold and during the Song period some superb and delicate objects, few of them preserved, were made. Since the Tang dynasty, and later under the Song, new techniques and repertoire arose. One of the most striking masterpiece of the history of jade is on display in this exhibition. It is an open-work dish with a dragon motif, which can be probably attributed to the Liao or Song dynasty from the 11th century.

The Production of Jade Objects

The production of jade objects seems to slow down during the Yuan period, probably because the Mongol invaders did not share this passion for the stone and preferred gold vessels to jade. However, the few solid vessels produced under their short reign were a great source of inspiration to the emergence of a new industry of jade carving in Central Asia, near Samarkand, not far from a native centre of extraction of jade, around Khotan and Kashgar area. A brush washer with phoenix-shaped handle display strong similarities to the dragon-shaped vessels which were carved under the Timurid dynasty from 1425 onwards illustrates this point.

Timurid Jade

An unpublished piece from the Jacquemart-André collection is a glorious testimony to the powerful art of Timurid jade from the Asian crossroads. The dragon-handled, quadri-lobed cup, clad in a mantle of gold and silver inlays, was bought at the Pourtalès Sale in Paris in 1865. It shows clearly a debt to Chinese art, but it also shows that a different aesthetic had been created.

This type of work reached Europe and the royal treasuries of the great courts of Europe during the 16th and 17th centuries. A jade-handled hanap from the collection of Louis XIV was created in the same area, but arrived probably in the French royal collections after the diplomatic visit to France of the ambassador of the Siamese king Phra Narai (1683), along with pieces of Ottoman jade and other Timurid pieces.

European Taste and Desire

From this period onwards, the passion of jade was to spread all around the Europeans courts. In Versailles, there is a fine collection of jade from China, Timurid and Ottoman periods. Mughal jades were also displayed during the reigns of Louis XIV and Louis XV in Versailles. Included in the exhibition is Cardinal Mazarin’s (1602-1661) exceptional jade bowl.

Jade had become international – in China the Qianlong Emperor received many Mughal-jade objects as gifts and tributes. An exhibition of this famous collection was organised in the southern branch of the NMP in Taiwan, Chiayi, earlier in 2016. A precious curiosities box made for the emperor shows the strong influence of Mughal jade on Chinese objects.

Chrysanthemum-Shaped Bowl

A Chrysanthemum-shaped bowl, from the A Thiers Collection, now in the musée du Louvre, carved in the 17th century, was engraved with a poem by Qianlong reminding us that he composed no less then 47 poems on jades from ‘Hindustan’. The emperor was especially fond of these pieces – he praised their smoothness to the touch, the purity of their design, and the transparency of the walls of the vessels. He also collected Mughal jades inlaid with precious stones and enamelled kundan and gold.

During the 19th Century

In the 19th century, China was politically weak and suffered many attacks from Western countries trying to open its huge market. After the Taiping and the Boxer Revolution, the relationship came to a violent head. In 1860, the emperor and the court fled the Yuanming Yuan palace to escape the encroaching enemy.

The foreign troops, among them the French, entered the palace and the building was sacked, pillaged and later destroyed. This traumatic moment brought back to Europe a large amount of precious objects of Imperial provenance. Some of these objects were acquired by Napoleon III and Eugénie early in 1861, after they had been seized by French officers and soldiers.

The Sacking of the Summer Palace

The sacking of the Summer Palace was heavily condemned by Famous French writer Victor Hugo. However, the objects which are on display in the musée chinois in Fontainebleau are still a tribute to the love for Chinese art – and especially jade. Around 40 works of art from this prestigious collection are also in the Guimet’s exhibition.

It is the first loan from the Fontainebleau Musée Chinois to the Guimet. At the fall of Napoléon III after the disaster of Sedan (1870), the palace of Fontainebleau managed to keep and preserve these treasures.

Jade in the 1920s and 1930s

Was this a source of rediscovery of Chinese greatest art? We are not sure. What we do know is that in the 1920s and 1930s in Paris, China’s decorative art was to play a key role in the formation of a new taste, especially in Art Deco jewellery.

Some drawings in the archives at Cartier are testimony to the frequent visit to the Guimet museum as a source to find new inspiration. Moving into recent times, on display for the first time is the famous Burmese jade necklace of Mrs Hutton, which radiates with mystery and is a wonderful final point to this jade retrospective.

BY SOPHIE MAKARIOU

Until 16 January at Musée Guimet, Paris, www.guimet.fr. A catalogue edited by Huei-Chung Tsao and Marie-Catherine Reay, accompanies the exhibition