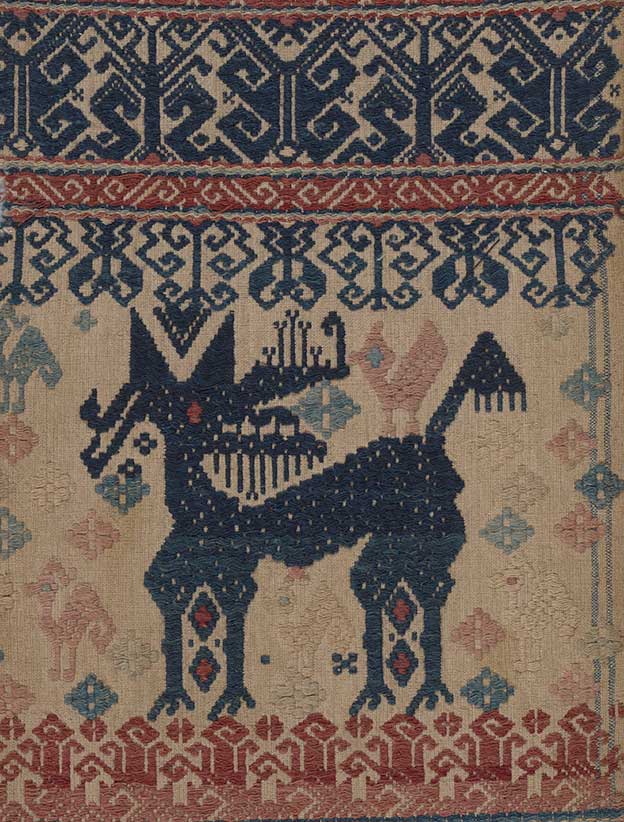

Cåelebrating the rich textile heritage of Indonesia, this exhibition explores the ancient inter-island links found in this vast maritime region. Textiles and textile trade have a long and continuous history in Southeast Asia, with these cloths showing the changing outside influences, fashions, and tastes of the diverse cultures found in the archipelago. The exhibition’s title, Nusantara, stems from the original name for the Indonesian archipelago and offers a broad overview of the wealth of imagery in these textiles alongside their remarkable technical mastery.Cloths from Bali and the Lesser Sunda Islands and southern Sumatra are on show alongside those from Sulawesi, in particular from the Toraja region, as well as ritual examples from Borneo and resist-dyed Javanese batiks.

On display are more than 100 examples showing their superb craftsmanship and artistic innovation, offering an opportunity to explore the cultural and historical significances of one of the finest collections of Indonesian textiles in the Western Hemisphere. The textiles, from the 14th to the 20th centuries, are drawn from the gallery’s holdings that are central to the gallery’s Department of Indo-Pacific Art. The textile collection also comprises approximately 1,200 examples from Indonesia and Sarawak (Malaysia). Significant pieces in this exhibition come from a collection of over 600 textiles originally acquired by Robert J Holmgren and Anita E Spertus, later presented to the gallery by Thomas Jaffe.

Indonesia has historically been at the crossroads of major trade routes, resulting in a blend of Indigenous and foreign influences. In the 10th and 11th centuries, Indonesian textiles began to show the influence of Indian designs in their creation. Cloth from India, particularly Gujarat, was exported to and traded in all parts of the Indian Ocean.

The impact of Indian textiles on local island traditions was expressed in many different ways. There were often changes of design as well as changes in the techniques used. Hand-painted cotton textiles produced on the Coromandel Coast were mainly traded to Sumatra, with the bulk of the pieces being block-printed textiles. These cloths were an essential commodity for the Southeast Asian trade and the dynamics of the Maritime Silk Road.

The impact of Chinese and later Islamic cultures is also evident, yet these borrowed motifs were transformed into distinctively Indonesian traditions. More is known about Indonesian textiles after the establishment of the early island Hindu and Buddhist trading empires, such as the Mataram Kingdom (Hindu, 4th to 11th centuries), the Majapahit Empire (Hindu-Buddhist, 13th to 16th centuries), and the Srivijaya Kingdom (Buddhist, 7th to 13th centuries).

The designs on Indian trade cloths come from many sources of inspiration brought across the Indian Ocean by visitors from all levels of society – sailors, warriors, traders, and religious leaders. These silks and cottons, batiks and brocades, tie-dyes, and embroideries display scenes from the Hindu epic The Ramayana, as well as depictions of elephants and other animals, trading ships, and a wealth of complex floral designs borrowed from Indian chintz.

Trade between the eastern coast of India and Indonesia was facilitated by the trade winds, allowing a constant stream of traded goods to flow between countries. At the heart of this trade was India’s Coromandel Coast – the centre of a textile-producing region famed for its technical mastery of block printing and use of mordants to fix dyes. Intricate patterns could be produced on plain cloth rather than using the traditional and time-consuming method of handweaving. These brightly coloured fabrics were used as major trading items, traded in Indonesia for spices that were valued in India.

The influence of Hindu imagery was felt most strongly in Bali, which remains Hindu today. Stories from the Indian epics were also used to design temple hangings for the island’s Hindu temples. Tree motifs, especially the stylised tree of life, were popular designs commonly found on Indian palempores (bed covers or hangings), and other textiles explicitly made for the European market. Textiles for the European trade were also found in Indonesia, as well as the double ikat patola clothes made in Gujarat for the Indonesian trade.

In Indonesia, Indian cloths were adapted to fit indigenous cloth forms of ceremonial textiles, such as those created in Sulawesi by the Toraja people. The block-printed, repeated geometric floral designs of Indian patola reappear on sumptuous silk- and-gold-thread Sumatran/Malay textiles called songket that intricately weave gold and silver threads into the cloth to form a pattern, as well as being incorporated into the batik cloths of Java.

The textiles from the islands of Sumatra and Sulawesi hold an important place within the gallery’s collection, counting more than 200 and 100 examples each, respectively. The remainder of the collection encompasses textiles from regions throughout Indonesia, showcasing the country’s rich cultural diversity. In many of these societies’, textiles are exchanged by women before marriage – and at other rites of passage, coming of age, the birth of a child, or at a funeral. They are also closely related to wealth and can have talismanic and health-giving properties.

Textiles can also be used to indicate a change in social status. In many regions, they were integrated into traditional belief systems, taking on the role of ceremonial cloths that were shown only during special occasions. It is the reverence with which they were treated that has allowed some of these cloths to survive in unfavourable climatic conditions. These cherished textiles were often stored in baskets hung from the rafters of the principal clan house in the village and protected with insect-repelling herbs and fragrant woods to help protect them from damage.

Sumatra is an island of diverse cultures which has had close contact with India, the Malay, and Arab worlds, and trading links with Europe and China for centuries. These trade and social contacts produced their own unique styles of textiles. Lampung, the southernmost region of the island, has been influenced by the Buddhist Srivijayan kingdom to its north, and to the south lie the powerful trading kingdoms of Java. In this region, long ceremonial cloths were used in various rituals, which were hung behind the principal person during the ceremony. Each cloth’s design would be woven to represent a certain situation, such as the representation of the ‘upper world’ using images of ancestors, ancestor shrines, and birds. Others show earthly dwellings and animals, or human figures. Other cloths from this culture are used as women’s skirts known as tapis that show elaborate designs and are most often associated with marriage.

Refined batiks from Java’s royal courts were highly localised cultural expressions made and used within the immediate neighbourhood of the palace. The origins of batik as an art form have been attributed partly to Hindu-Buddhist influences from 8th- century India, which were modified with the spread of Islam. A known technique in Southeast Asia certainly by the 14th century, batik displayed distinct features from the Hindu-Buddhist ethos, which were incorporated and absorbed into the Javanese psyche. The advent of the Sultanate of Mataram Empire

(1582-1755), the last major independent kingdom on Java before being colonised by the Dutch, however, exacerbated the Islamic conversion of Hindu Java. Islam’s aversion to the portrayal of human and animal forms left Javanese culture submitting to change and cultural reconsiderations in fashion and design.

In central Java, batik is a distinct art form ranked alongside court dance (joged), poetry (tembang), drama (lakon), percussion orchestra (gamelan), and shadow puppetry (wayang kulit) as one of six gentry (priyayi) applied arts. Batik as costume had sacred connotations and was considered protection for the body. Its early history suggests it was crafted to be worn by those of high social status and, while used to wrap a newborn infant, was also believed to have healing power for the sick.

By the late 18th century, batik was given exalted status as ceremonial dress. Motifs reserved for use solely by the Sultans of central Java began to be formalised. Edicts pronounced specific motifs ‘restricted’ or ‘forbidden’ (larangan) and exclusive to the court. As sacred heirlooms (pusaka) handed down from one generation to the next, they were confined to the privileged within the palace compound (kraton). This meant that batik motifs became an index for hierarchy and a visual sign of social order.

In September, to record this vast range of textiles that incorporate a myriad of designs, cultures, and beliefs, the gallery has produced a digital catalogue of their Indonesian textiles. Indonesian Textiles at the Yale University Art Gallery is a free born-digital publication that catalogues the museum’s approximately 1,200 textiles from maritime Southeast Asia and is organised by geographic area, with each region introduced by a brief overview of its notable features, history, and textile traditions. An appendix of scientific research findings rounds out the study, which has produced exciting new evidence of inter-island connections discovered by the authors during their analysis of these complex and culturally significant works.

Until 11 January 2026, Yale University Art Gallery, artgallery.yale.edu

Catalogue available