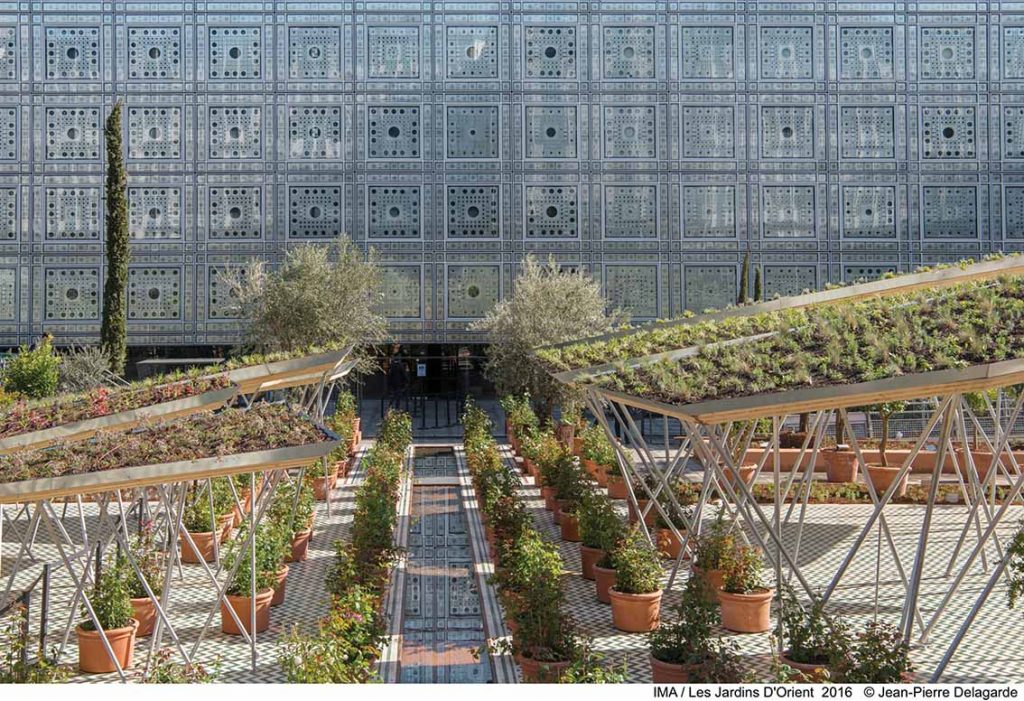

The Institut du Monde Arabe has designed a wonderful exhibition in five parts that retraces the history of gardens of the Orient from earliest antiquity to the most contemporary innovations, from the Iberian Peninsula to the Indian subcontinent. The intstitue itself has a garden that recreates the world of Arab/Islamic gardens in Paris. The exhibition explores this history and styles of classic gardens – ancient and modern – looking at ancient sites In between the Tigris and the Euphrates, where civilisations emerged with the development of the first cities that also gave rise to gardens.

Faced with such an arid environment, the Arabs and their predecessors had and have always used water in an economical way in order to irrigate their ornamental and food-producing gardens. From the Hanging Gardens of Babylon to the Al-Azhar Park in Cairo, the Alhambra in Granada to the Trial Garden of Algiers, and from the princely garden to the garden for everyone, they are all part of a fascinating itinerary, whose central feature is the essence of all life in gardens: water.

The Tree of Life as a Symbol in Gardens

In these gardens of the Orient, they created abundant gardens with trees, where plants flourished under these trees and the ‘Tree of Life’ became both a symbolic image as well as a reality. These oases transformed the arid places into areas of natural abundance, depicted as an earthly paradise by poets and where architects built palaces that constitute classic symbols of the Oriental civilisations. The Hanging Gardens of Babylon, the Alhambra, the Taj Mahal and, closer to home, the Majorelle Garden in Marrakech, are all a veritable source of inspiration.

Gardens of the Orient in the Fertile Crescent

These gardens of the Fertile Crescent, an abundant geographical region surrounded by large dry-zone areas were able to develop with the emergence of oases – expanses of water bordered by palm trees that contrasted sharply with the aridity of the surrounding desert that emerged in Mesopotamia around 6,000 years ago. This led to the development of the first water management techniques, including the famous subterranean drainage tunnels that collected water from the water tables, which enabled farmers to manage agricultural production.

Use of Water and Irrigation in Gardens of the Orient

Water – a source of life in the heart of these arid regions – became an essential element in Arab-Muslim gardens. Thus the creation of the style of the Arab-Muslim garden was closely associated with these scientific, technical, urban, and artistic revolutions that took place in the Orient between the 8th and 11th centuries that resulted in the development of great expertise in channelling water, involving specific calculations, estimations, and principles.

Sustainable garden irrigation was made possible by collecting groundwater by means of wells linked by subterranean tunnels – the qanat water-supply system. It was the beginning of a new era – the ‘golden age’ of the Arab-Muslim qanat systems. (https://johnsonchimney.com) Thus, the water determined the layout and form of the gardens in the form of canals and large basins, around which were arranged a series of beds containing flowers, plants, and vegetables.

The Garden as a Hidden Space

This Oriental garden was – and is – also a private often ‘hidden’ space. Derived from the Greek word paradeisos, which means ‘enclosure’, the Oriental garden is enclosed and divided into equal parts, separated by canals with the fountain or water source at the centre.

The garden at Pasargadae, a paradigm par excellence of the Persian garden, was primarily based on the geometry of the beds and the irrigation network that demonstrates a complete mastery of nature, the green vegetation, and the water circulation. It can therefore be seen as the first example of a geometric garden divided into four equal parts, known as the chahar bagh, a model that has been used throughout the history of these type of gardens.

Associated with Notions of Power and Command

From very early on, the gardens of the Orient have been associated with notions of power and command: many princes organise official receptions in the garden to enthral their guests and to express their power. The luxuriance of the garden, in contrast with the drought and the barrenness of the landscapes, is the clearest mark of power. The belvederes, dominating the whole garden and its environment, allow the monarch to have a symbolic view over the whole of the kingdom.

The sovereign is seen as a magician who makes the desert bloom, his garden is an inviting place. The Assyrian kings were probably the first to assert their power through the creation of ornamental gardens, which were made possible by considerable development and water-conducting systems that they built.

They stamped the garden with the royal seal by representing themselves celebrating and enjoying life in the shady arbours of the garden. Moreover, the garden became an essential component of town and surrounding lands since it connected them to the palace – lots of Persian gardens extend to the town and even further into the desert, just as the axis of the Taj Mahal continues beyond the Jamuna river.

Designed to be Full of Flowers, Trees, and Plants

To give a luxuriant feel to these gardens, they are designed to be full of flowers, trees and plants: cypresses, bay trees, plane trees, pines and many types of fruit trees and scented plants all feature prominently in their design, as do tulips, roses, jasmines, and anemones. The planting design uses a natural geometry that favours shade and creates intimacy in different areas of the garden.

Gardens of the Orient Are Associated with the Senses

The gardens are also associated with the senses: the perfumes, the appealing geometry, and the babble of running water and the splash of the fountains all appeal to our senses. Protected from prying eyes, the garden exalted the senses and encouraged pleasures.

As in One Thousand and One Nights, the garden is a place for contemplation and enjoyment of intimacy, conductive to a romantic rendez-vous. It is a space of transgression – it becomes the theatre of lovemaking and is subject of many literacy descriptions in which young princes reign over the flowers in the garden and the flowers become the metaphor of a young lover’s beauty.

Matching the scale of the dwellings, palaces and territories, and created according to religious or secular principles, the various forms of these gardens have expressed an aesthetic, spiritual, and political ideal. They have symbolised visions of the world, which have been continually created in gardens in which fundamental natural elements are arranged: water, stone, and, in particular, plants. These gardens have now been brought to life in the heart of the city of Paris.

Oriental Gardens: From the Alhambra to the Taj Mahal, 19 April to 25 September, 2016, Institute du Monde Arabe, Paris, www.imarabe.org