According to common belief, Islam has an absolute ban on images and is hostile to pictorial representations, quite in contrast to Christianity. But is this actually true? Are images categorically forbidden in Islam? And what about Christianity: does not Moses’s Second Commandment state ‘thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image’? With this in mind, how does one explain the existence of so many ‘Islamic’ miniatures, ceramic bowls, and textiles bearing human representations? And, on the other side, how does one account for the widespread and popular veneration of statues in Catholic churches? In other words: what is the ban on images in Islamic and Christian cultures actually about? How did people in former times deal with figurative representation, that is, the depiction of human beings, especially of Prophet Muhammad and Jesus Christ? This exhibition deals with questions such as figurative imagery in Islamic art on a comparative, cross-cultural basis.

Aniconism

It traces the strategies Islam and Christianity applied over the centuries to deal with aniconism. The focus is on the Middle Ages, the period from the 6th to the 16th century. During this time, the question of images was debated extensively by theologians. The 136 works on display cover a geographic area that stretches from Latin Western Europe (Kingdom of France and Holy Roman Empire) to the eastern Mediterranean (Byzantine Empire and later Ottoman Empire) to Western Asia (Persia) and as far as South Asia (Mughal Empire in India).

In the Christian West, it was the Church that ruled over religious images. Starting from an initial rejection of imagery, the Church developed over time an image theology with the venerated cult image at its core (either an icon or a statue). However, this development did not unfold without resistance: twice in the period under review a serious dispute about the role of images arose, once in the 8th/9th century and then again during the Reformation in the early 16th century, in the course of which countless religious pictures and statues were destroyed.

Madhhabs, The Schools of Law

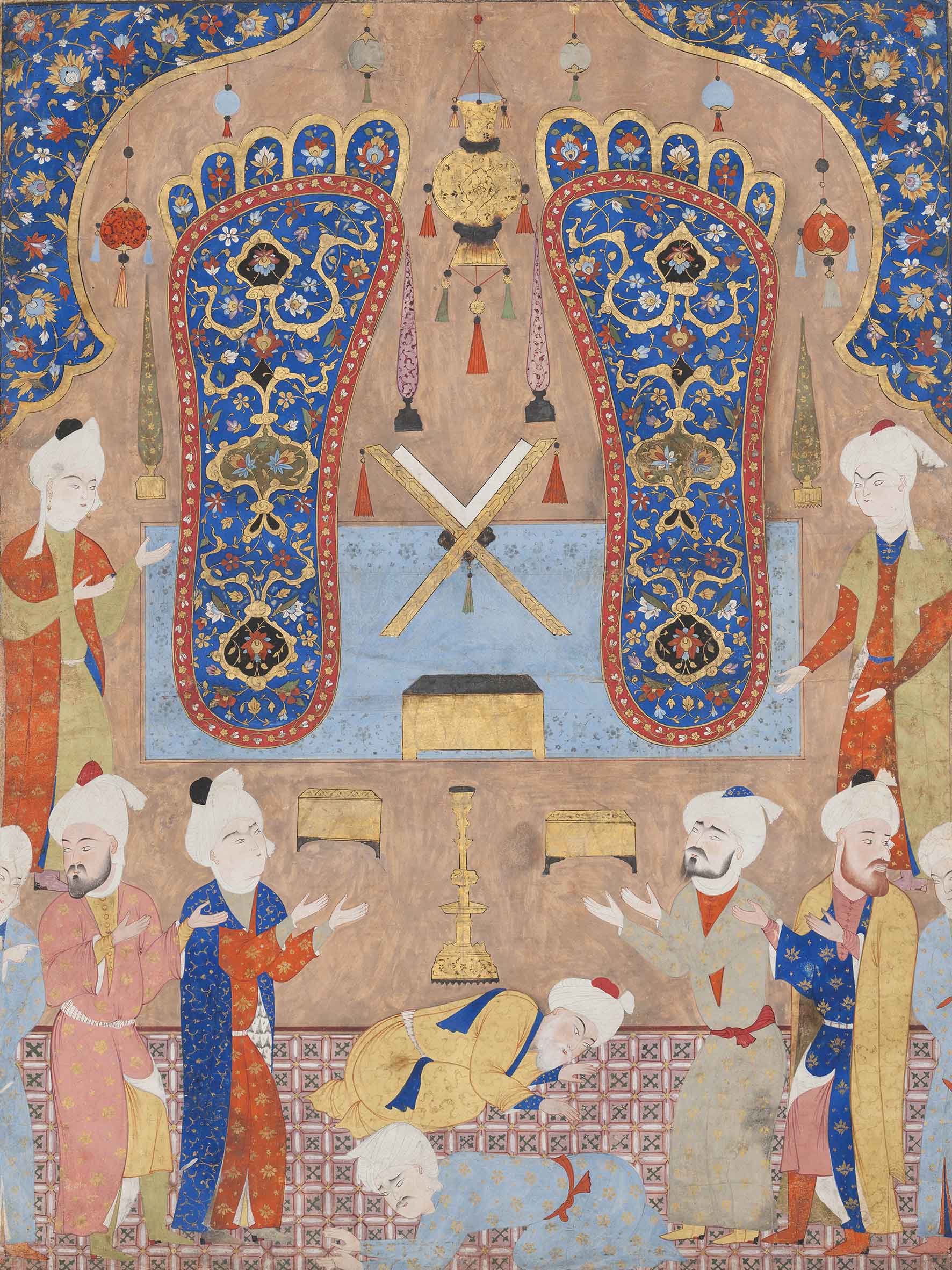

In the Islamic world, matters developed more peacefully. Here it was the madhhabs, the schools of law, that decided whether an image was to be ‘prohibited’, or merely considered ‘reprehensible’. There was never any doubt that images had no place in mosques and religious ceremonies. In all other areas it was, time and again, left up to the individual actors to negotiate the question of images within the framework of existing social power relations. Under these conditions, a rich pictorial culture developed at the princely courts of Persia, the Ottoman Empire, and the Mughal Empire in India, while in North Africa religious images were treated with utmost reservation.

Different Approaches to the Ban on Images

In the course of history, the faithful of Europe and North Africa, Western and South Asia developed entirely different approaches to the ban on images. They range from outright rejection of the visual representation of living things – human and animal forms, in other words – to the installation of sculptures. Even the question of what is meant by this prohibition, and what type of image it pertains to, is answered very differently. As a general rule, it can be said ‒ and this applies to both religions ‒ that aniconism stems from fear of idolatry, and that the devotional image and the narrative image are central to the theological debate. The devotional image ‒ i.e. the icon ‒ is venerated; the narrative image illustrates a story. One makes the divine visible; the other depicts historical, poetic, but also religious events in the form of an illuminated manuscript or mural painting. While the devotional image has a role only in Christianity, the narrative image is known in both culture areas.

Debate surrounding the image is not limited to the spiritual sphere, however; it applies to the secular sphere, too. Sultans and kings used the portrait to illustrate their claim to power and to legitimize their authority. The model in the East and West alike was the iconography of antiquity, whether Sassanian or Roman. Distinctive forms of imagery emerged in Persia, the Ottoman Empire, and in Mughal India.

Qajar Portraits

They were characterised as much by antiquity’s ‘Science of Physiognomy’ as by dynastic pride that was associated with the idea of divine legitimation. While these likenesses were long limited to small formats and circulated only within the elite, close contact with Europe gradually led to the emergence of large-format portraits like that of the Persian ruler Fath-ʿAli Shah Qajar, gifted by the sitter to Napoleon I of France in 1805

In the exhibition of figurative imagery in Islamic art, the Rietberg asks the question – are the medieval debates on images of relevance to us today? And supplies the answer – yes, namely for two reasons: the exhibition does away with a long-held prejudice, as mentioned at the outset. And secondly, it comes to the conclusion that we are living in times that are shaped and defined by images as never before. Images are omnipresent and readily available, every hour of every day. Although we might be aware of the manipulative power of images, we often tend to view them uncritically.

Until 22 May, 2022, In the Name of the Image: Imagery between Cult and Prohibition in Islam and Christianity, figurative imagery in Islamic art, Museum Rietberg, Zurich, rietberg.ch