This intriguing exhibition takes a nuanced approach to questions of artistic voice, gender and agency through more than 100 works of painting, calligraphy, and ceramics by female Japanese painters from 1600s to 1900s Japan, with many of the artworks being on view for the first time to the public. It traces the pathways women artists forged for themselves in their pursuit of art and explores the universal human drive of artistic expression as self-realisation, while navigating cultural barriers during times marked by strict gender roles and societal regulations. These historical social restrictions served as both impediment and impetus to women pursuing artmaking in Japan at the time.

To explore these complex themes, the exhibition is organised into seven sections, each representing different realms in which artists found their voice and made their stamp on art history. Subtle design choices borrowing from traditional architecture and materials – such as paper and ink, plastered walls, sliding doors and tokonoma niches – distinguish and allude to each of the spheres presented in the exhibition. The artists featured include Kiyohara Yukinobu (1643-1682), Otagaki Rengetsu (1791-1875), and Okuhara Seiko (1837-1913), as well as relatively unknown yet equally remarkable artists like Oishi Junkyo (1888-1968), Yamamoto Shoto (1757-1831) and Kato Seiko (fl 1800s).

Female Painters in a Cultural Content

An introductory space to female Japanese painters presents the two major themes of the exhibition: artists’ pathways to art, and art as agency. Each gallery evokes a different cultural context, within and through which artists pursued their art. Whether being born into a family of professional artists or becoming a nun for the freedom to produce art, the groupings do not pigeonhole the artists as identities. Instead, they highlight how women navigated their personal journeys as artists. In the exhibition, many of the artists can and do appear in more than one section, shuttling through these spheres, despite the strict limitations imposed on them by the time’s gender roles and class hierarchies.

The next section is entitled ‘The Inner Chambers’ (ooku) and refers to the secluded areas where women primarily resided within the courts and castles of the upper class. The term became synonymous with women and reveals the gender segregation in the upper echelons of early modern Japan. Daughters born into elite and wealthy households studied the fundamentals of ‘The Three Perfections’ (painting, poetry and calligraphy). This artistic education was intended to prepare them to be proper companions for the men in their lives; they were not expected to become working artists. Included here are works by exceptionally driven and talented women who leveraged their unique access to education to become artists in their own right. Included in this section are works by Nakayama Miya (1840-1871), Oda Shitsushitsu (1779-1832) and Ono no Ozu (1559/68-before 1650).

Daughters of The Ateliers

In the third section, ‘Daughters of The Ateliers’ (onna eshi) visitors discover the world of professional artists. Painting traditions were commonly passed down in the form of apprenticeships or from father to son. In this manner, some lineages endured for centuries. These professional painters subsisted through the patronage of wealthy clients. Artists in this section emerged from artistic families and, thanks to their talent and tenacity, established themselves as successful professional artists themselves. They were able to continue their family’s artistic legacy, while developing a distinctive style and voice. Included in this section are works by Kiyohara Yukinobu, Nakabayashi Seishuku (1829-1912) and Hirata Gyokuon (1787-1855). Yukinobu (1643-82) was related to the celebrated artist Kano Tany’u (1602-1674), who founded the Kano school, the official school of painting instruction for the Tokugawa shogunate, and creating the shin-yamato-e painting style that illustrated scenes from traditional Japanese stories and legends. Yukinobu often depicted female figures, persons of historical note, Buddhist icons, shin-yamato-e content and natural scenery such as flower and bird paintings, all of which were popular themes at the time

Female Japanese Painters in the Edo Period

Hanako Brown in her essay on female Japanese painters remarks that the Edo period gave rise to many successful women artists, those who were professional and equal in their successes to their male counterparts, but additionally the forgotten domestic artists whose interest in creative pursuits were shaped by the societal standards of the time. Deftness in painting, poetry and calligraphy were all deemed acceptable interests for women in this era. However, although the existence of female artists in the Edo period was widespread and undeniable, their subject matters and styles were somewhat corrupted by the patriarchal standards for painting at the time. In order to gain popularity and establish herself as a prominent artist, one may have to submit to the creations of popular bunjin (male literati)subjects and a limitation of techniques deemed suitable for women to emulate.

Japanese Buddhist Nun Painters

The next section, ‘Taking the Tonsure’ (shukke) sheds light on the world and work of Buddhist nun artists. Taking the tonsure, the shearing of one’s hair to join a Buddhist monastic order, was a symbolic act of leaving one’s past behind and becoming a nun. Shukke literally translates to ‘leaving one’s home’. Subverting expectations, this section brings works by Tagami Kikusha (1753-1826), Otagaki Rengetsu, Daitsu Bunchi (1619-1697) and others for whom taking the tonsure did not mean relinquishing autonomy. On the contrary, it offered them a form of liberation from societal expectations, such as ‘The Three Obediences’ (sanju) of a woman to her father, husband and son. It also enabled nuns to travel freely in times of state-imposed restrictions, which especially impacted women. Above all, it allowed them the freedom to pursue their art. Leaving their old names behind and taking new names as ordained nuns, these artists crafted new identities for themselves.

Otagaki Rengetsu

In the online catalogue, Melissa McCormick discusses the work of the poet, painter, and ceramicist Otagaki Rengetsu and her status as a Jodo Buddhist nun. She explains that Rengetsu’s work challenges assumptions concerning the gender identities of historical subjects. Active for over 50 years as an artist after taking Buddhist vows, Rengetsu, and other nun artists of her era, demands a nuanced approach to gender beyond static notions of female and male. Since she removed physical markers of conventional lay femininity – shaving her head, donning simple robes, taking the name Rengetsu (Lotus Moon) – her identity can be understood through a contextualised lens that accommodates the historically contingent nature of gender categories. Although aspects of her artistic identity and self-expression may seem straightforward, Rengetsu’s work often demonstrates an engagement with a Buddhist philosophical tradition that questions the very nature of the self and artistic subjectivity.

In ‘Floating Worlds’ section (ukiyo), the ‘floating world’ refers to the state-sanctioned quarters or urban entertainment districts, which catered to male patrons who frequented the teahouses, brothels and theatres. The term alludes to the ephemeral nature of this realm. Entering it, whether as a musical performer (geisha), an actor or a courtesan, meant leaving behind one’s name and constructing a new persona. Entertainers often cycled through several stage names, inventing and reinventing themselves time and again.

The Three Perfections in Japanese Art

Being well-versed in ‘The Three Perfections’ was a coveted trait in women of the floating world, adding to their allure. Some, however, transcended the strict confines of the pleasure quarters, sometimes even undoing their indentured servitude, becoming important artists and leaving their literal mark by creating artworks that were collected and cherished for generations. Alongside calligraphy by Tayu, commonly translated as ‘grand courtesans’, this section introduces works by the ‘Three Women of Gion’, who were not prostitutes, but rather owners of a famous teahouse. The three became formidable artists, in effect forming a matriarchal artistic lineage.

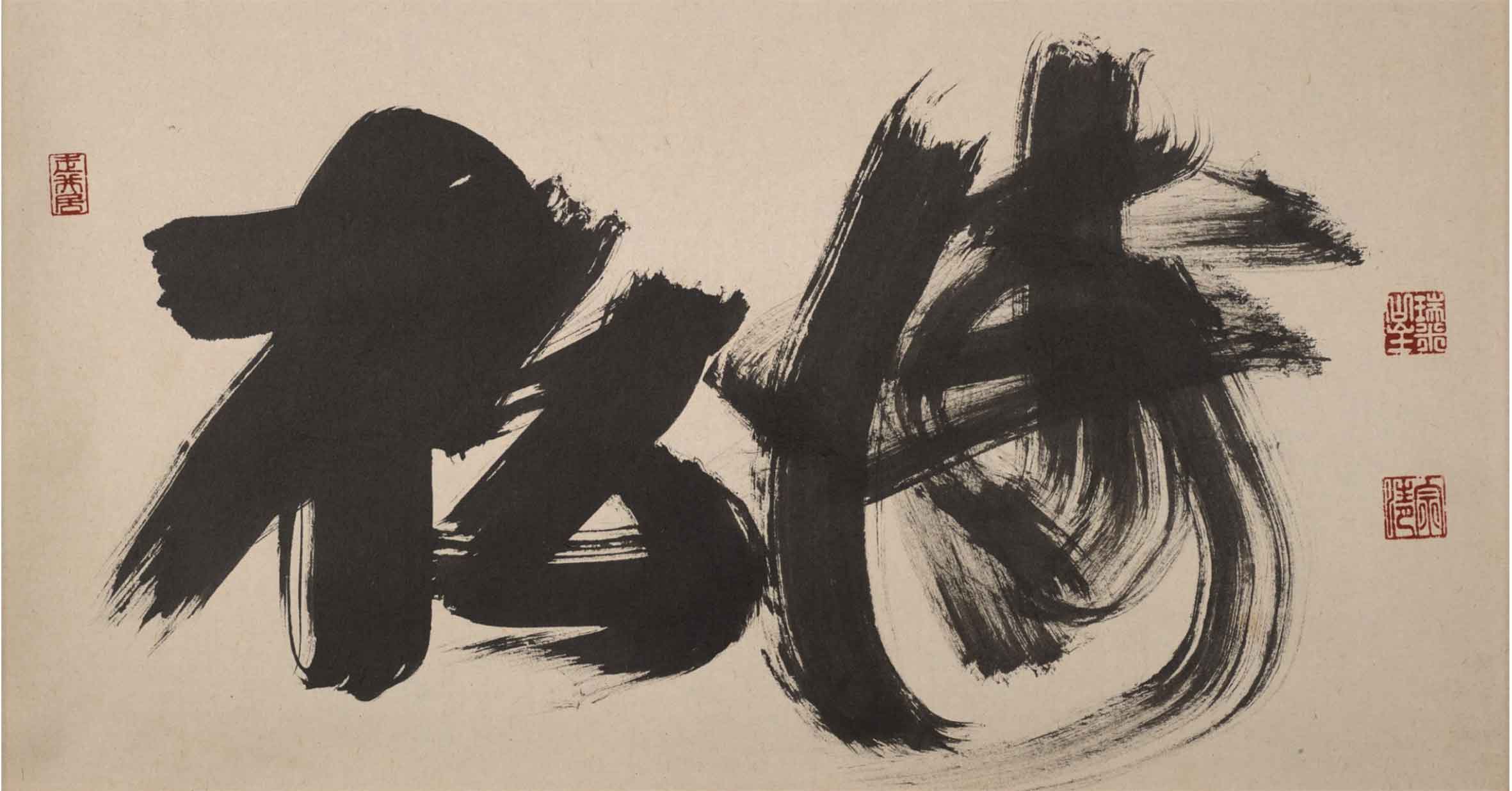

The sixth section, ‘Literati Circles’ (bunjin), features literati societies united by a shared appreciation for China’s artistic traditions. For these intellectuals and art enthusiasts, art was a form of social intercourse. Together, they composed poetry, painted and inscribed calligraphy for one another. Literati painting (bunjinga) prioritised self-expression over technical skill. Following this understanding of the brushstroke as an expression of one’s true self, artists in this section conveyed their identity and personhood through art.

As in other social contexts explored in this exhibition of female Japanese painters, literati circles included women from diverse backgrounds. More so than any other sphere introduced in this exhibition, literati circles were accepting of women participants. Many prominent women artists in Edo and Meiji Japan flourished within these intellectual cliques, including Okuhara Seiko, Noguchi Shohin (1847-1917), Ema Saiko (1787-1861) and Tokuyama (Ike) Gyokuran (1727-1784), the latter being one of the Three Women of Gion.

The concluding section, ‘Unstoppable (No Barriers)’, takes its name from a double- sided screen by Murase Myodo (1924-2013). On one side, it reads: ‘no’, or ‘nothingness’. On the other side, it reads ‘barriers’. When considered together, the two characters spell ‘unstoppable’, or ‘no barriers’ (mukan). Each of the works in this gallery, including paintings and calligraphy by Takabatake Shikibu (1785-1881), Otagaki Rengetsu and Oishi Junkyo, addresses the subject of perseverance, overcoming personal and societal obstacles, and shattering the glass ceiling. Otagaki Rengetsu wrote, ‘Taking up the brush just for the joy of it, writing on and on, leaving behind long lines of dancing letters’.

Until 13 May, Her Brush, Denver Art Museum, Colorado, denverartmuseum.org