This exhibition, Diamond Mountains, on Korean art, organised by Soyoung Lee, Curator in the Department of Asian Art, is part of a celebration marking the 20th anniversary of the establishment of The Met’s Arts of Korea Gallery and coincides with the 2018 Winter Olympics in Pyeongchang, South Korea.

The Korean peoples originated as a single genetic group in the Altai Mountains of western and southern Mongolia from whence they emigrated some 5,000 years ago from an area with an average elevation of some 6,000 feet. Their arrival on the now-Korean peninsula was greeted by the Taebaek Range of mountains which extends much of the length of the eastern edge of the peninsula. Very similar to their home in Mongolia, the Taebaek Range has peaks of equal height and above. Being a shamanist society, the Koreans perceived these very familiar-looking mountains as reservoirs of powerful spirts and great beauty, a belief still held by all Koreans, regardless of religious beliefs.

The Area Diamond Mountains

The part of this range considered the apogee of spiritual beauty is the area extending along the now-North Korean coast referred to as the Diamond Mountains. In essence the mountains are part of the cultural glue which binds all Koreans into one. The centre of greatest importance is Mt Geumgang and its surrounding area – the Diamond Mountain among the Diamond Mountains. Because of its great spiritual beauty, iconic status and emotional pull, it was one of the earliest and most important Buddhist sites created in the 6th and 7th centuries by both Goguryo and Silla dynasties.

Decline of Temples

Both the Korean War and disinterest by the North Korean government in restoration have conspired so that there is only one functioning temple left on Mt Geumgang, once home to several important temples and over 100 secondary ones. Pyohunsa, built in 670, is that single one surviving today, despite all of its treasured contents having been taken by the Japanese. Changansa (once a prisoner of war camp for North Korea), Yukomsa, Mahayeonsa and Singyesa, all built in the late Goguryo or early United Silla dynasties, were completely destroyed during the Korean War. Bokeudam, built in 627, is still intact, but abandoned as structurally unsafe.

Religious Hermitages

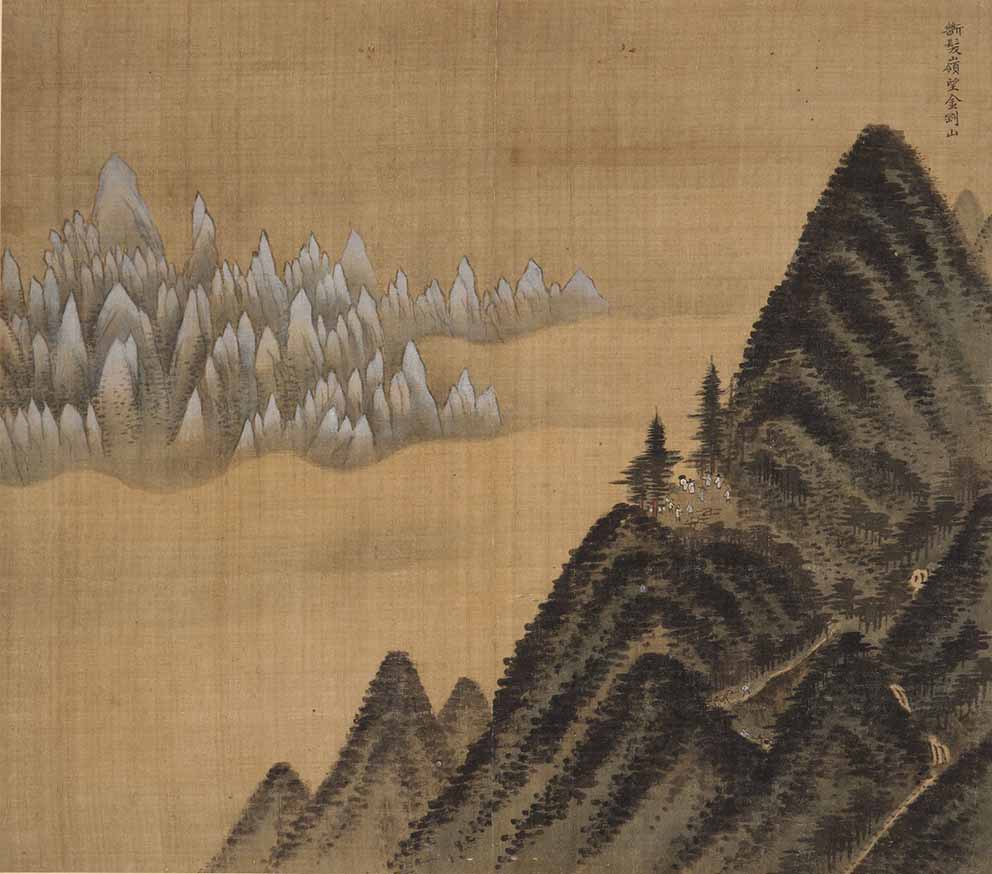

It was the power of place that drew these religious hermitages and it was this very same power that, especially in the 18th century, drew artists in a human attempt to capture the majesty and the spiritual beauty of this remarkable creation of Nature. Of the existing depictions of Geumgang or any other parts of the Diamond Mountains, the best and most original are the works of Jeong Seon (1676-1759) and his National Treasure album masterwork is the highlight of this exhibition. Very much in the same way Huang Hui did at the same time in China, he not only broke the rules, he created new ones. In the 17th century, Korean landscape artists were still under the almost static sway of the Chinese Northern School.

The Korean Painter Jeong Seon

Jeong Seon, however, broke that mould by creating the most important painting development style of the 18th century, true-view landscape (chin-geyong sansu). He was not a professional painter but a gentleman-scholar, yangban, who worked on his paintings as if he were. He had studied the Chinese School of Practical Learning as well as the styles of both Northern and Southern Chinese Schools. He assumed some of the Southern methods, especially the use of strong outlines, but his various influences were combined with his own creative genius, making his paintings unique within the Korean opus. With his brush, often used as if it were carving its way across the painting’s surface, emphasised the strong lights of the high points and the profound darkness of the lows, in a way depicting the contrasting balance between the feminine and the masculine.

The exhibition contains more than this remarkable National Treasure album, for it contains nearly 30 landscape paintings, most never having been seen in the US, from delicately painted scrolls and screens to monumental modern and contemporary artworks covering the period from the 18th century to the present day.

BY MARTIN BARNES LORBER

Diamond Mountains, until 20 May at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, metmuseum.org