The Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library at Yale is currently showing Textured Stories: The Chirimen Books of Modern Japan, The exhibition explores Japanese crêpe-paper books, known as chirimen-bon, which feature handmade pages filled with stories drawn chiefly from Japanese fairy tales and folklore.

Produced between the 1880s and the 1950s, these illustrated books played a crucial role in the dissemination of knowledge and cultural expression during a time of significant transformation in Japan as the country navigated modernisation and articulated its national identity. Chirimen-bon provided new ways to envision Japan’s culture and heritage. Among Western audiences, these books provided insight into a society and culture that had been largely unknown.

The exhibition traces the history, production, and distribution of chirimen-bon and explores their stories, cultural impact, and enduring legacy through 70 books that showcase the creativity of their publishers, artists, authors, and translators, revealing how chirimen-bon drew upon long-standing literary and artistic traditions to envision and share cultural narratives in new ways.

The Rosenberg Library Museum in Texas also has a collection of chirimen-bon, including the works of Hasegawa Takejiro (1853-1938), who was probably the most famous publisher in this genre and specialised in publishing books on Japanese subjects in various European languages. Originally published between 1885 and 1922, many of these books were reprinted over decades, and revised editions were produced containing new sets of illustrations, utilising different traditional and modern binding techniques.

Hasegawa’s publishing company emerged just as the Japanese government was transforming society to adapt and benefit from a rapidly modernising world. During the Meiji Restoration, starting in 1868, Japan re-emerged from centuries of almost complete self-isolation, providing a fresh source of fascination and delight in the Western world. At this time, the government was assertively engaged in international trade and recruited technical experts from around the world to help fast-track its industrialisation and modernisation.

Hasegawa’s Fairy Tale series began as a way for young Japanese children to learn English when Japan had just recently reopened trade with the West after 300 years of isolation. The publishing house hired Europeans residing in Japan to translate well-known Japanese folk tales into English and other languages, and had notable Japanese artists create the illustrations for each story. The series quickly became popular among Westerners who lived in or visited Japan and was eventually exported to booksellers overseas.

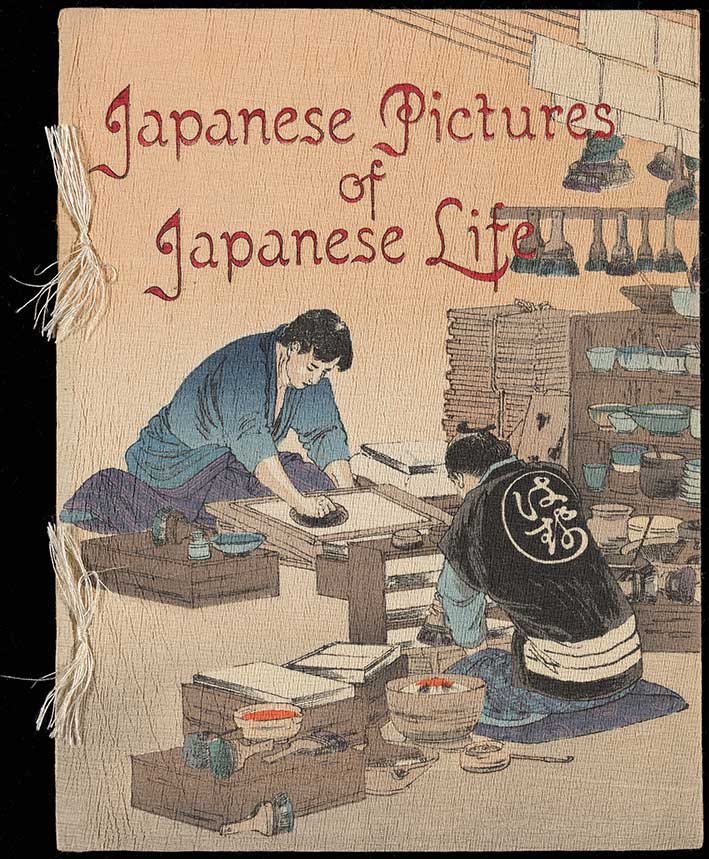

In chirimen-bon, the text and illustrations were printed on washi (Japanese paper) using hand-carved woodblocks, and the paper was then crinkled to create chirimen (crêpe paper) and bound together into book form using silk thread. The result of the crinkling process is a very soft, textured paper that feels almost like cloth. Chirimen had been used in Japan previously to make kimono, furoshiki (wrapping cloth), as well as many other items centuries before chirimen-bon were first produced.

The fairy tales were released in two series between 1885 and 1903, with a total of 28 volumes with each volume being one fairy tale. The first five volumes contain what are often referred to as the Five Great Fairy Tales in the Japanese tradition: Momotaro, or Little Peachling; The Tongue Cut Sparrow; Battle of the Monkey and the Crab; The Old Man Who Made the Dead Trees Blossom; and Kachi-Kachi Mountain. Japanese folk tales were traditionally passed down orally rather than in writing, which resulted in many different versions of each story in different regions, but these five stories seem to be the most frequently repeated and most widely known – much like Cinderella and Snow White in the West.

There are a few key differences between Eastern and Western fairy tales. Japanese stories especially focus on philosophical and spiritual elements, with ghosts, demons, and other spirits appearing frequently. Animals also feature prominently as protagonists. In contrast, Western stories often portray individual heroes overcoming a struggle and are very action-focused.

The fairy-tale endings are also different: Western fairy tales usually have what we consider a happy ending, where good triumphs over evil and the princess marries the hero. Japanese fairy tales, on the other hand, often resolve on a note of melancholy, with the hero reflecting on their journey or contemplating the beauty of nature.

Allison O’Connell, in her essay Takejiro Hasegawa’s Fairy Tale Series notes, ‘Hasegawa successfully integrated aspects of traditional and modern technologies, and of Japanese and Western bookmaking, maximising the books’ appeal to a foreign market eager for collectors’ items and souvenirs. While the text of the stories was in Western languages and the books were formatted in the Western manner, to be read from left to right, the tales, illustrations, binding, and crêpe paper were all distinctly of Japanese origin. The crêpe paper editions were especially prized by Hasegawa’s foreign clientele as being uniquely Japanese, a feature which, together with their superior quality woodblock-print illustrations, elevated them to a collectable art form.

O’Connell continues, on Hasegawa’s recruitment of authors and translators, ‘The production of the Japanese Fairy Tale series involved the collaboration of several specialists with whom Hasegawa worked closely on every book. According to Basil Hall Chamberlain, one of the key authors of the series, Hasegawa only worked on one book at a time due to his personal oversight of every aspect of the production. The first point of collaboration was the engagement of Westerners who were skilled in either the translation of folk tales from Japanese into their native language or in the identification or writing of stories translated by others. The range of authors represented a cross-section of the Westerners living in Japan at the turn of the 20th century, including missionaries, university professors, and renowned Japanologists.

Whereas initially Hasegawa sought out the authors from among his close network of expatriate friends and acquaintances, as the series became more popular, he was increasingly approached with story proposals, as was the case with Lafcadio Hearn. An internationally recognised journalist and author when he moved to Japan in 1890, Hearn became a great admirer of the Japanese Fairy Tale series: in a letter dated 2 June 1894, Hearn wrote to a friend, “By the way your little boy must soon be beginning to study English, so I am sending a package of the Japanese Fairy Tales for him”. That same year Hearn convinced his friend Basil Hall Chamberlain to arrange a meeting with Hasegawa to show him “a number of tales splendidly adapted to weird illustrations” and ultimately became the author of five of the books in the series’.

While there were several talented illustrators of Hasegawa Takejiro’s Japanese Fairy Tale series, Kobayashi Eitaku is often considered the most famous, especially for the early volumes, before his death in 1890. Other well-known artists who contributed include Suzuki Kason and Chikanobu, who were already celebrated for their ukiyo-e woodblock prints and helped to make the series popular with Western audiences.

The Japanese Fairy Tale series remained popular for over 50 years, well into the middle of the 20th century, when the books became a victim of their own success, in that other publishers were inspired to produce competing collections of Japanese fairy tales. This competition combined with the general decline in sales of traditional Japanese prints saw an overall decline of the industry and their fall from popularity.

Until 3 May 2026, Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Yale University Library, Connecticut, library.yale.edu