A landmark exhibition of textiles of the Chin peoples, who traditional hale from western Myanmar (Burma), northeastern India, and eastern Bangladesh was held at The Textile Museum in its old location in Washington DC in 2006. The show included nearly 80 ceremonial mantles, tunics, and other garments, along with contemporary and historic photographs, plus jewellery and accessories worn with the textiles. It was the first major exhibition devoted to the textiles of the Chin, an ethnic group comprised of some two million people speaking 44 languages.

In 2015, a related exhibition Zo: Textiles from Myanmar, India, Bangladesh was held at The Philadelphia Museum of Art. For the Zo, a Tibeto-Burmese minority that comprise over 50 linguistic groups in Myanmar, India, and Bangladesh, weaving is considered the highest form of art and confers status on the maker and the wearer. The exhibition considered textiles in their historical and cultural context from Zo groups such as the Northern Chin; Southern Chin; Asho; and Khumi, Khami, and Mro, including mantles, tunics, breast cloths, skirts, loin cloths, and blankets worn for daily life and for ceremonial occasions such as weddings, funerals, and feasts of merit.

The focus of the Mantles of Merit exhibition was on culturally important textiles, so not all textiles were given equal weight. The great majority of the pieces discussed were woven on a back-tension loom and used in culturally important circumstances, particularly feasts and rites of passage ceremonies. Major textiles included blankets and tunics.

Little written history precedes events of the mid-19th century, as contact with the Chin by those outside the area prior to this period were limited, and the Chin had no written language. Consequently historians have had to rely primarily on anthropology and linguistics to decipher their ancient past. The Chin themselves have preserved an oral history, but without a written record they state accurately historic dates and details. When outside contact with the Chin became more frequent in the 19th century, records were mainly written by non-Chin observers who were culturally different, including British military administrators and European and American missionaries and scholars. It has been only in the last half of the 20th century that the Chin have begun creating their own written history.

Textiles play a central role in Chin social life, illustrating an individual’s success in achieving merit in this life and the next through worldly activities such as hosting feasts and bagging big game. The majority of the textiles in the exhibition were from the museum’s own collections, which was formed, in large part, by a donation to the museum by the exhibition’s curators, Dr David W Fraser and Barbara G Fraser. Their scholarship on Chin textiles was published in a definitive volume on the subject that accompanied the exhibition, Mantles of Merit: Chin Textiles from Myanmar, India and Bangladesh. The curators noted that they used ‘mantle’ as the generic term for Chin textiles in light of its definition as ‘something that enfolds, enwraps, and encloses’, as there is a near-total absence of tailoring in traditional Chin textiles.

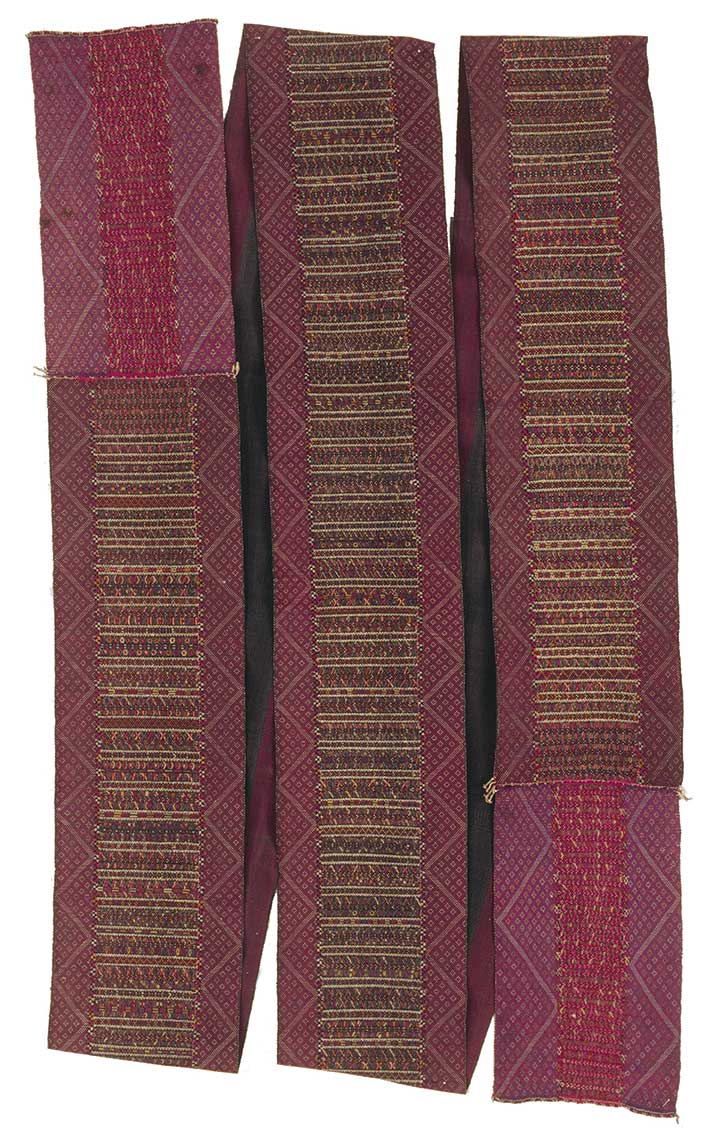

Despite commonalities of language and culture, the various Chin groups are broadly dispersed over adjacent hills of three countries, speak languages many of which are mutually unintelligible, and have textile traditions that vary widely. The section Mandalay to Chittagong introduced visitors to the important ceremonial textiles of the four major divisions of Chin: Northern; Southern; Asho; and Khumi, Khami, and Mro. As generalisations, the Northern Chin are distinguished by their fine blankets and hierarchical social structure; the Southern Chin by the simplicity of their textiles and their egalitarian social structure; the Khumi, Khami, and Mro by their narrow textiles with elaborate selvedge decoration; and the Asho by their fine tunics and their residence in low-lying and coastal areas as well as the hills.

The exhibition was organised around three themes: how textiles imply status within Chin culture, the migration of Chin weavers, and the resulting effects on their textiles, and how, over time, the designs of Chin textiles have grown increasingly complex while the techniques for creating them have been simplified. Generally, textiles signal the status of the wearer in several ways, playing their most dramatic role in the core Chin effort to achieve merit in this life and the next. Chin peoples have traditionally strived to distinguish themselves from their peers through accomplishments in hunting, war, wealth accumulation, and feast giving. These textiles made and worn by the Chin visually announced those accomplishments through specific patterns reserved for the meritorious.

Many Chin textiles also denote local subgroups and serve as emblems of community membership. Most are gender-specific and some are appropriate only for people of a certain age, marital status, high-status clan, or religious function. The Migration and Chin Textiles display proved that the migration of the Chin did not stop when they arrived from the Tibetan plateau 1,000 or more years ago. Chin oral history records waves of subsequent migration, many of them out of the northern Chin Hills, with migrating groups pressuring earlier migrants to move once more. As groups moved, they took weaving styles with them or acquired new styles from their new neighbours. One can trace some of these migrations by comparing textiles from the departure point and destination. Such comparison can also reveal the effect of imported materials, particularly silk, from non-Chin, lowland cultures.

The final section showed how Chin weavers use a simple backstrap loom in which the warp is circular and continuous. They use home-grown cotton, flax or hemp, often dyed with indigo or other locally produced natural dyes. The Chin repertoire of weaving structures is broad and varies by division. Some of the more important structures used by the Chin are warp-faced plain weave, weft-faced plain weave, twill, 1-faced supplementary weft patterning, two-faced supplementary weft patterning, false embroidery and weft twining – an ancient textile structure that predates the use of heddles (the sets of parallel cords that compose the harness to guide warp threads in a loom).

The earliest descriptions of Chin textiles date from 1800, whereas the oldest known Chin textiles were acquired in 1855. Since then, many changes have occurred in material and design. Two broad trends can be discerned. Over time, the structure of Chin textiles has become simplified, apparently as weavers chose easier ways to achieve the intended result. Simultaneously, the decoration of Chin textiles has tended to become more elaborate, covering a greater portion of the surface area and employing novel yarns and colours. Both the book and the exhibition aimed to document and best represent the fast-disappearing techniques and designs seen in the 19th century, which are heavily under threat from the modern world.

A book accompanied the exhibition: Mantles of Merit: Chin Textiles from Mandalay to Chittagong, which is still available.