Gyeongbokgung in Seoul is the primary, most visited, and best-known of the five royal palaces in Seoul. It is the iconic symbol of power and the Joseon state (1392-1910), but it is the smaller, charming Changdeokgung that steals the show. Referred to as the East Palace in Joseon times, as it was east of Gyeongbokgung. Changdeok means ‘to let virtues prosper’. It is an exceptional example of official and residential buildings that were integrated into and harmonised with their natural setting. Situated at the foot of a mountain range, it was designed to embrace the topography in accordance with pungsu principles (the Korean form of feng shui), by placing the palace structures to the south and incorporating an extensive rear garden to the north, called Biwon, or the Secret Garden. Other considerations of traditional architecture included the use of dancheong decoration and japsang, the animal-shaped tiles placed along the ridge and eaves of a roof that serve both decorative, symbolic, and shamanic purposes. They show the grandeur of a building and chase away evil spirits and misfortune, as well as adhering to Confucian principles.

The construction of the palace began on the auspicious site in 1405 on the orders of King Taejong (1367-1422), to be used as a secondary palace of the Joseon dynasty. After its destruction during the Japanese invasion and the Imjin Wars (1592-1598), it was rebuilt in 1610 by Prince Gwanghaegun (1575-1641), who was regent from 1592-68; it then served as the main palace for approximately 270 years.

Like many Joseon palaces, Changdeokgung comprises official, military, civil, and domestic buildings sprawling over a large complex with numerous courtyards, back alleys, and a large open square. Injeongjeon Hall (Hall of Benevolent Governance) is the main throne hall that was used for holding the most formal state events, such as audiences with ministers, coronation ceremonies, weddings, and receptions for foreign envoys. State ceremonies during the Joseon period were classified into one of five categories, and collectively known as the Five Rites of State. The first was Auspicious Rites, which included memorial services to royal ancestors; the second, Felicitous Rites, such as royal weddings and birthdays; the third Guest Rites, for receiving foreign envoys; the fourth is Military Rites, such as the king’s ceremonial military review; and the fifth relates to Sorrowful Rites – royal funerals.

This main hall was also used for the national examinations for recruiting officials to the palace. The Joseon rulers were committed to the cultivation of talented people and their selection into government service. Civil officials, military officers, and people with special skills were selected through three separate examination systems, collectively known as the gwa-geo. The king himself presided over the final palace examinations, held in the capital, Hanyang (now Seoul), for the civil and military candidates. The Ceremony for Announcing the List of Civil and Military Examination Passers was attended by the king, civil and military officials, and relatives of the successful examinees, where the king granted certificates and special flowers, eosa-hwa, made of paper to the successful candidates. The top achiever of the civil examination also received a type of parasol to show his achievement.

In 1454, the Joseon court adopted a system of insignia of rank for civil and military officials based on that of China’s Ming dynasty (1368-1644). Square badges of embroidered birds and animals on silk were worn on the front (hyung) and back (bae) of official costumes. They are clearly differentiated from the round badges embroidered with a dragon (called bo) worn by the king and the crown prince on the front, back, and shoulders of their court attire. Besides being ornamental, rank badges served as visible status markers in a Confucian society that prized strict social and political hierarchy. The rank system of government officials during the Joseon dynasty comprised nine ranks, from first to ninth degree. Each rank was divided into junior and senior positions, and the posts above the junior sixth degree were also divided into upper and lower classes, in keeping with Neo-Confucian thought. These divisions and classifications made a total of 30 ranks, with civilian and military officers identified by the rank badges worn on their outer garments. Initially permitted for wear by civil and military officials of the third rank and higher, eventually the use of rank badges was broadened to all nine ranks. Regulations on the specific animal imagery and correlating ranks evolved over the course of the Joseon dynasty.

The interior of Injeongjeon Hall was remodelled in Western style during the reign of King Sunjong (1874-1926) with the traditional black brick flooring replaced with parquet flooring and the installation of electric lamps. The ceiling has kept its traditional coloured dancheong decoration with lotus flower and bonghwang (Korean phoenixes) patterns. This practice, literally ‘balance and contrast between red and green’, is the method of ornately painting wooden buildings that was reserved for royal palaces, Buddhist temples, and Confucian institutions during the Joseon dynasty. Kwon Yj-eun, in her essay on the subject, Dancheong: A Signifier of Architectural Function and Status, writes, ‘Dancheong also served as a signifier of architectural hierarchy. Historical records from the Three Kingdoms period (57 BC–AD 668) to the Joseon era confirm that decorative colouring was applied only to buildings with public purposes and of high status, such as royal palaces, Buddhist temples, government buildings, and Confucian schools, and that the styles of colouring them were organised according to the specific purpose of a building. The ornamental painting of a building symbolised both its practical function and hierarchical position, distinguishing it from other structures and imparting a sense of sacredness and dignity’.

Other important objects in the main hall include the striking Sun, Moon, and Five Peaks (irworobongdo) screen. The traditional pattern of the screen was an innovative way to identify the position and presence of the king. The sun and moon symbolise yin and yang, with the five peaks representing the four cardinal directions and the central location. Flowing water and trees indicate both changing and unchanging qualities in the world – bringing together all the elements that represent the universe. The throne was located front and centre of the screen, showing the ruler’s place at the centre of this universe, giving a sense of power and control – and a visual representation of the authority of the king. This iconic design is found on other screens and paintings, with about 20 extant examples known today. It was first used at Gyeongbokgung, which was especially created for the first ruler of the Joseon dynasty, King Taejo

(r 1392-98), the first Joseon king.

In Joseon palaces, the throne is elevated and sits at the centre of the hall with the irworobongdo screen as the backdrop, with a wooden canopy above the throne, the same as that placed over statues of the Buddha in Korean temples. The throne always faced south on platforms reached by several stairs. Besides the thrones seen in the royal palaces, only two other thrones are known to exist – now housed in the National Palace Museum of Korea.

The large courtyard in front of the hall was used for important state events, including the audiences with the king, called jocham, when all civil and military officers greeted the king on specific mornings each month. Enthronement ceremonies were also held here. In keeping with the principles of pungsu, the stone terraces at the back of the hall were built to relay the vital energy from the Baekdu-daegan mountain range, which runs 1,500 km the length of the peninsula.

The next large building, Seonjeongjeon Hall, is the king’s council hall and the only structure remaining at Chandeokgung with blue-glazed roof tiles. Here, a daily audience with the king, called sangcham, would be held when the ministers, high-ranking officials, court recorders, and other dignitaries would attend to discuss affairs of state. The blue roof tiles were demanded by Gwanghaegun, when he was acting as regent during the Japanese invasion, instead of the conventional dark grey tiles, as he wanted to build a striking and imposing building. Court records note that they were costly to create, as they required a glazed firing. A scribe noted, ‘How can we now think that we can make Seoul stand out only by glaze firing the roof tiles of the throne hall with extremely expensive greyish blue pigment made from nitre. It must be imported from thousands of kilometres away, especially during this hard period when the nation is facing difficulties due to carrying out an unnecessarily grand scale palace construction. I deeply feel regretful that the officials in charge of the ad-hoc committee will insist on doing everything in such a luxurious and excessive manner despite the difficulties, not even one person appealing and trying at all to correct the negative consequences of such custom’.

Continuing the journey through the palace, the Huijeongdang Hall, or king’s residence, was considered the royal bedchamber as well as an informal workplace for the king. It burnt down in 1917 and the current building dates from 1920, modelled in Western style but with materials taken from Gyeongbokgong. This gives the residence a very different feel – a car port was also introduced for the king. The royal residences were separated, in keeping with Confucian thought, with the king’s residence in Huijeongdang Hall and the queen’s quarters in Daejojeon Hall. Other buildings in the complex include buildings specifically used for study, as well as an apothecary, shrine, and the government office complex.

A highlight of the palace is a tour of the Secret Garden to the north of the main buildings that remains frozen in time. It was created as a large leisure garden and is the epitome of Joseon-period landscaping, taking up almost 60% of the entire area of Changdeokgung’s grounds. It preserves the original topography with garden areas planted in the lower ground alongside a series of lotus ponds. The garden, as it looks now, was primarily modelled by King Sejo (1417-1468), the second son of Korea’s most famous monarch – King Sejong, who is renowned for creating Hangul, the Korean alphabet, as well as his significant contributions to Korean culture and intellectual life. The existing garden pavilions date to King Injo’s reign (1595-1649). The garden was intended as a place for the king and royal family to relax, a royal retreat, as well as the location of various popular outdoor activities such as archery. Male members of the royal family would also join in military exercises that were organised in the garden’s precincts.

The main hallmark is Buyongi Pond, an artificial feature with a man-made round islet to one side that is modelled on the Taoist cosmology thought that heaven is round and the earth is square – bringing harmony to heaven and earth. This round-square association was intended to reflect the balance between the celestial and terrestrial realms, considered essential for the well-being of humans and the universe. The pine tree on the islet is associated with longevity and immortality and represents the immortals’ realm, allowing the visitor to ponder the elusive ideal of eternal life.

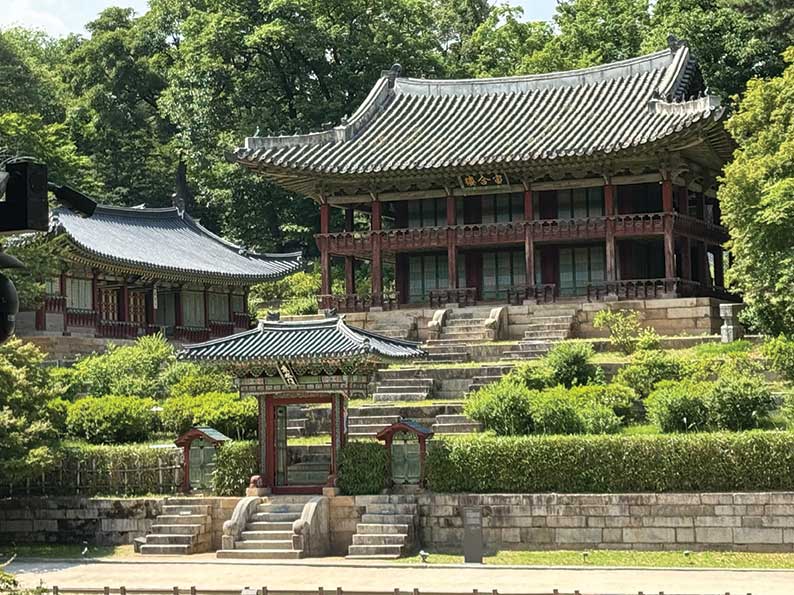

The two-storey pavilion overlooking the pond houses the Gyujanggak (Royal Archives), with the upper floor being the reading room, Juhanmu – which translates as ‘a place opening on to the universe’. A perfect spot to end the exploration of Changdeokgung.

Reading: In Grand Style: Celebrations of Korean Art During the Joseon Dynasty, published by the Asian Art Museum, San Francisco; Korea: A History by Euguene Y Park

The five royal palaces in Seoul are Changdeokgung, Gyeongbokgung, Changgyeonggung, Deoksugung, and Gyeonghuigung

National Palace Museum of Korea, gogung.go.kr