The usual reaction to the mention of Western shipwrecks is that one most commonly thinks of Spanish 16th- and 17th-century treasure galleons that originated in the Spanish colonies in the New World and were sunk by hurricanes along the middle of Florida’s east coast, known now as the Treasure Coast. For Asian shipwrecks, however, one usually thinks of 10th/15th-century Chinese, Arab, and other Asian commercial vessels plying the South China Seas, Indonesia, and the Indian Ocean to the Persian Gulf.

The Hoi An Hoard

This exhibition is an odd juxtaposition of two Asian shipwrecks, four centuries apart, two oceans apart, both with similar cargoes from what is modern-day Vietnam. They both met with watery fates; one sank around the year 1500 just offshore from its home port in what is now Vietnam; the other, in 1877 off the coast of Somalia. The vessel that sunk near Somalia was, before its recent discovery, unknown, except for international maritime registries of lost vessels. The vessel that sank off the coast of Vietnam, however, is a completely different matter. It is very well known to the worlds of undersea archaeology and Asian ceramics – The Hoi An Hoard.

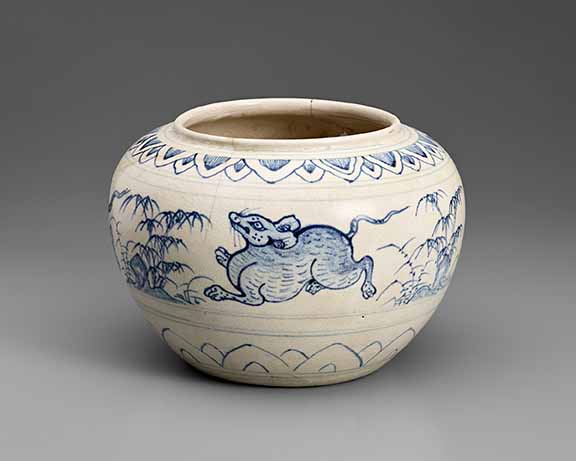

The story began about 500 years ago with a large, ocean-going merchant ship on Vietnam’s Red River docking near the Chu Dau kilns where it was loaded with some 250,000 pieces of predominantly blue and white porcelains destined for export. It left the port at Hoi An but had not sailed far from home before it sank in one of the South China Sea’s severe storms and lay undisturbed until the 1990s when fishermen found broken porcelain shards in their nets.

The Sale of the Cargo – Blue and White Ceramics

The sale had been previously valued as a whole at US$14 million, but failed to reach anywhere near that, with the strong prices clustering around the star pieces. The two Butterfield sales of Asian shipwrecks had a large number of pieces that failed to sell, and many have been reoffered at a number of small auctions ever since. The remaining pieces are available on eBay in the general range of US$100-300.

The museum has been gifted a number of genuinely ‘high end’ porcelains from this hoard through the kindness of local supporters of the museum. This makes it possible for visitors to discover the remarkable quality, decoration, design and creation undertaken by the potters and painters involved with the creation of these Vietnamese porcelains found in Asian shipwrecks.

One such example is a blue and white ewer based on a classic Islamic metal shape. What distinguishes this vessel is the pierced and openwork panel affixed to the two sides. Other shapes made solely for export are water droppers in the shapes of birds and also of recumbent elephants and from the varied shapes and traditional trade routes, it is probable that the vessel’s course would have been the Philippines, modern-day Indonesia, India and the Persian Gulf.

The second vessel is a late 19th-century French ship, the Le Mie-Kong, carrying cargo which sailed from French Indochina, modern-day Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia, destined for France via the Suez Canal. On board were some 24 stone carvings that a French colonial official had removed from a ruined temple in the area of the ancient Cham Kingdom, aka the Kingdom of Champa (2nd to 19th century.) Like its neighbour, the Khmer Kingdom, the Kingdom of Champa was also Hindu and fell under the cultural and artistic shadow of the Khmer. Their architecture and sculpture were basically provincial Khmer and have always been considered so.

The Ship Le Mie-Kong

On board the ill-fated Le Mie-Kong, which sank just off the coast of Somalia in 1877, were the stone carvings, as well as a cargo of Vietnamese blue and white porcelains. For almost one 120 years they lay undisturbed at the bottom of the Arabian Sea. When the contents of this ship were retrieved in 1995, the stones and blue and white porcelains were sold off and dispersed. Some of the porcelains and two of the stones were bought and gifted to the museum and are major components of this exhibition of Asian shipwrecks.

One of the stones is that of Naga, a multi-headed snake who served as a protector of Vishnu and is frequently serving as a divan on which Vishnu reclines. Naga also serves the same protective purpose, this time serving as a throne for the Buddha Shakyamuni at Lopburi and elsewhere in the late Khmer period, comprised of his coils and protected by his spread, multi-headed hood.

An Iconographic Oddity

The second stone from the Asian shipwreck is an iconographic oddity, starting with the demonic face at the base. One fable about Vishnu was that when the earth was being overrun with destructive demons, he created a super-demon whose assignment was to kill all the demons rampaging on earth, which he did.

Vishnu felt that with his great strength and ferocity, this demon could become independent. With that, he ordered it to consume itself. It began, starting at his feet. It had eaten up to its chest when Vishnu changed his mind and ordered it to stop. Vishnu felt that it could serve perfectly as a protector to humans and now it is a common tradition to have its image of arms with claws and a ferocious head with fangs above doorways for human protection. The reason for this tale is to possibly identify the female figure in its back. As this figure is closely associated with Vishnu, the only female that it could be is Lakshmi, Vishnu’s consort. The combination of the demon and the goddess is unorthodox, but may be attributed to a local Cham belief.

If one pays attention only to the dates of the shipwrecks, the exhibition would appear counter-intuitive, but the point being made by this cleverly planned exhibition is that the time capsule of a wreck does not coincide with the time capsule of its contents. The exhibition points out that marine trade routes (as well as overland, such as the Silk Road) prove that globalisation is nothing new.

Together with the works of art on view, there are exhibition components about marine archaeology and the complex ethical issues surrounding it.

BY MARTIN BARNES LORBER

Until 22 March, Asian Art Museum of San Francisco, asianart.org