YANG ZHICHAO IS arguably China’s most extreme performance artist, who has used his body as a medium to comment obliquely on social issues and to examine the place of the individual within Chinese society. He has cut, pierced, burned, and stabbed his body, had appendages attached, used his blood to draw with and endured life as a beggar for several days – it is a litany of self-imposed suffering for art.

Mostly the performances were done without anaesthetic and, for Yang, the inevitable pain became a critical component of the experiences. ‘I want to feel the pain. It is part of the performance for me and becomes more real with the pain,’ he explained, speaking at his studio in Beijing in March this year.

Iron 2000, for example, concerned heating up an electric branding iron onto which Yang’s personal identity number had been cast. His friend, Ai Weiwei, held the iron against Yang’s right shoulder for five minutes leaving a permanent burn mark as a reminder of the erroneous individuality bestowed on citizens by the Chinese government; not a name, not an identity per se, but a number.

Yang Zhichao Performance Works

Performance works are inevitably ephemeral and what remains is the documentation of the event. Now we look at photographs of Yang having a metal disc inserted permanently into his leg (Hide 2002), or a plastic phial of earth into his stomach (Revelations No 1: Earth 2004), or infamously shoots of grass from the Suzhou Creek planted into two incisions in his back (Planting Grass 2000) – with a curious detachment.

The distance from the event imposed by time makes it almost impossible for us to emphasize with the pain the artist must have felt. ‘Everybody experiences pain at some time,’ Yang said. He excuses and qualifies the pain by saying, ‘Our bodies were not allowed to belong to us,’ during the early years of socialism when China robbed the individual of any real sense of selfhood in pursuit of collective identity and absolute discipline to the communist ideology.

Extreme Performances Now Stopped

These extreme performances have now stopped and Yang has entered a calmer phase of his artistic life, driven as much by the encroachment of age – not that he is old, he was born in 1963, the Year of the Rabbit – as it is by a re-focusing of his vision to match a more contemplative frame of mind. His daughter who is nineteen and currently studying in America was also instrumental in bringing about this change. Some time ago she told him that the extreme violence and self-harm simply had to stop.

Exploring these issues was at the core of Yang’s performances. But more recently Yang, who is a devout Buddhist, reciting mantras almost daily, has found a way to reconnect with individual selfhood in work that is free of any violent self-harm but yet still fulfils the criteria or performance.

Created Chinese Bible in 2008

In 2008, Yang Zhichao created Chinese Bible, an installation of 3,000 diaries and journals written by ordinary people and scoured by Yang from the flea markets of Beijing over a three-year period. From 2005, he spent most weekends visiting Beijing’s Panjiayuan flea market. Known locally as the ‘Dirt Market’ Panjiayuan has become a Mecca for anyone wanting to forage among the recent cultural heritage of China; books, documents, artefacts, porcelain, antique furniture spill across the footpaths of the sprawling market.

‘In 2004, I started collecting old books at the flea market. Then, in 2005, I found several diaries and knew immediately that I had found something of cultural and social importance, a history of ordinary people during a critical period of China’s recent past. I knew that I wanted to do something with this. My heart was so troubled and I was overwhelmed, I had a sense that I was recreating history,’ he said.

Yang Zhichao spent days reading the books that began to accumulate in his studio. ‘I was so shocked by what I read. Here in my hand was a record of ordinary people’s lives from the early years of socialism. This was a history about people. Not heroes but the daily lives, the daily struggle, the happiness, and sorry or ordinary people. Suddenly I had the idea that I would do an installation work called Chinese Bible,’ he continued.

Four Pests Campaign

The various books he bought had no real intrinsic value and he would pay between 5 and 200 yuan and often the books were little more than crumbling documents with fraying red and green covers with inside pages heavy with age. But for Yang Zhichao it was the contents that were important. He recalls one book of particular significance for him, which he believes was written by a woman, that tells the story of Chairman Mao’s Four Pests Campaign, initiated in 1958 to eradicate pests such as mosquitoes, flies and rats.

The fourth pest was sparrows, included because they ate the peasant’s grain. She wrote of taking to the streets to bang pots and pans to keep the sparrows flying until the dropped and died from exhaustion, and she told of her personal sorrow as so many birds died around her. It touched Yang’s heart. ‘I have read this book many times and always its makes me feel emotional,’ he said.

Over the ensuing years he was to find many more journals and diaries detailing the early years of socialism and the years after Mao’s death in 1976 when the country began its path to prosperity and when Chinese citizens were gradually able to express more openly their views on the world and the society in which they lived.

Over 3,000 Journals Used by Yang Zhichao

The 3,000 journals and diaries that were brought together as Chinese Bible, cover the years 1949 to 1999 and offer up an extraordinary insight into a period when personal histories had been largely ignored and what has emerged is multi-layered work part anthropological, part socio-political, but wholly artistic, with the potential to contribute significantly to an enriched understanding of the first 50 years of socialism in China, a period mediated through the prism of Mao Tse Tung’s opaque political expediency.

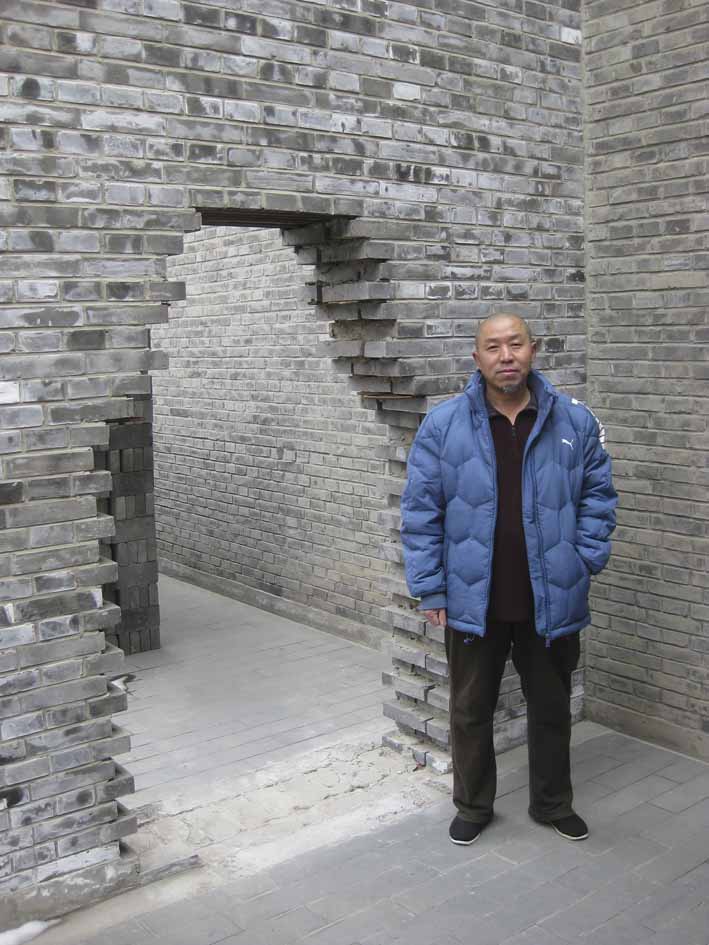

Yang Zhichao lives and works in an immense studio home in Beijing with soaring six-metre ceilings that has a minimalist design aesthetic. The building was designed by Ai Weiwei, who lives close by and has been a close friend and associate since they first met in 1994. Barely a week passes when the two do not meet to discuss art. Yang openly acknowledges the debt he owes to Ai Weiwei. ‘He is my teacher and mentor. He taught me everything about contemporary art.’

It was Ai Weiwei who first identified the importance of Chinese Bible as a culturally significant document that needed to be seen and it was Ai who, in 2009, was the first to exhibit the work at his Art Document warehouse. Since then the monumental installation has been shown at Beijing’s 798 art zone, twice in Hong Kong, and once in Singapore. But not so far in the West. However, that is about to change.

Yang Zhichao’s Chinese Bible Now Permanently Overseas

Earlier this year the work moved quietly and permanently overseas when it was bought by Australian collectors Brian and Dr Gene Sherman whose collection of Asian art now numbers more than 800 pieces.The Chinese Bible’s ‘significance as an art work struck me … forcibly. The importance of the work as a socio-political document covering the second half of the 20th century in China felt awesome,’ Dr Sherman explained.

Yang Zhichao is happy with the overseas sale. While he has a refined sense of political and personal injustice he remains staunchly apolitical in his life while acknowledging that the period covered by Chinese Bible is a dark one for Chinese socialism, one that needs to be addressed before it become obscured in historical inaccuracy.

The rubric of communism demanded an individual’s subservience to the collective and anonymous writers of the diaries employed ingenuous ways to articulate their private concerns, thoughts and observations through allusion. But many also repeat the party line and many of Mao’s despotic mantras pour from the pages.

Keeping A Diary

Even keeping a diary during the early years of communism was an activity frowned upon. One incautious word, one thought critical of the regime especially during the period of the Cultural Revolution could see a writer denounced as a capitalist with dire consequences. ‘In the early 1950s people had freedom. After mid 1950s you could not write anything personal. During the Cultural Revolution you could only write about politics.’ One day Yang found a book with a recipe in it. ‘I was so surprised because you are not allowed to write about these things. If someone were to find out you are writing about recipes and food they could report you and you would be in serious trouble. Commenting on the food you were eating would be considered capitalist and not socialist,’ Yang Zhichao expanded.

The Chinese Bible deals with a time in China of momentous change. Dr Sherman sees the work both as a multi-layered piece that functions as a monumental modernist grid in hues of red, and as socio-political document of critical importance and she plans to exhibit the work in Sydney in 2015 at a major collaborative exhibition, between the Sherman Contemporary Art Foundation and the Art Gallery of New South Wales. ‘From the birth of Mao-style communism through the triumphs, agonies and eventual demise of his vision, the personal diaries paint a portrait of arguably the most intense 50 years in modern history,’ she said. Over the intervening months Dr Sherman will have the work translated so as to more clearly identify its social relevance.

For his part Yang Zhichao has no interest in learning the identities of the writers. ‘Some of the writing is very funny,’ he said, often ‘recording every word that Chairman Mao said or wrote. Some of the diaries also seemed to serve as a writing exercise as though the writer was trying to memorise Mao’s sayings. Everyone, especially during the Cultural Revolution wanted to be seen as a follower of Mao’.

‘When I went to Hong Kong for the exhibition a lot of people there told me I must never sell this history to any European people and that it should be kept in China. But I think a lot of European people will appreciate and look after this art. I know it is now in good hands and know that eventually it will be displayed and exhibited permanently to the public,’ Yang Zhichao said.

BY MICHAEL YOUNG

Information on the Sherman Contemporary Art Foundation in Sydney