XU BING IS one of China’s most influential living artists. For more than 25 years his works have been challenging, probing and teaching a diverse global audience. In this time he has developed a rich artistic idiolect. His ground-breaking early works such as Book in the Sky (1987) paved the way for the Chinese contemporary art movement along with such artists as Ai WeiWei and Zhang Huan to explore China’s rich artistic history and question its historically turbulent political landscape.

Centrality of Language to Xu Bing’s Practice

A current exhibition at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) highlights the centrality of language to Xu Bing’s practice. Xu Bing trained as a printmaker at the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing and as such, an awareness and understanding of the physical elements that comprise a language has since permeated his artistic practice.

Displaying a small number of iconic works such as The Character of Characters (2012), this exhibition is modest in scale, seeking only to explore one aspect of Xu Bing’s opus. The over-arching aim, however, is by no means conservative: the curators want the juxtaposition of works from across his oeuvre to encourage a dialogue, and for this in turn to provide the audience with a fuller understanding of Xu Bing’s approach to writing and language.

Square World Calligraphy Classroom

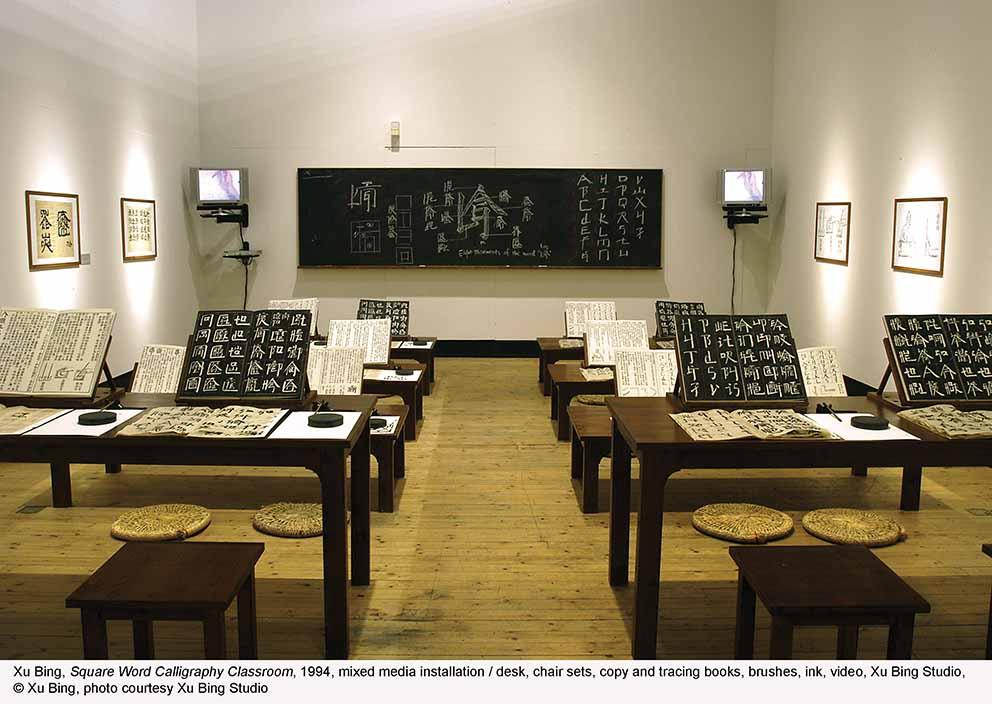

Another exhibition highlight is Square Word Calligraphy Classroom (1994) – an interactive piece where visitors are invited to learn, decipher and practise writing pseudo-Chinese and English characters. The work is testament to the both enlightening and perpetually didactic qualities of Xu Bing’s work. The show’s assistant curator, Stephen Little, speaks to Asian Art Newspaper about the myriad levels on which language infects Xu Bing’s art and the importance of tactility to inspire and engage new Western audiences.

Asian Art Newspaper: Have you worked with Xu Bing before?

Stephen Little: No, I have not worked with Xu Bing before. I have followed his work since 1995, however, when I was first introduced to him in Chicago by the scholar and academic Wu Hung.

AAN: How was the exhibition conceived? How did you decide which pieces to include?

Stephen Little: This exhibition was originally conceived and installed by our former Assistant Curator of Chinese Art,

Dr Christina Yu (now the Director of the USC Pacific Asia Museum in Pasadena). In planning this show she worked closely with New York collectors Rene Balcer and Carolyn Hsu, and with Xu Bing’s studio in Beijing. Christina Yu made the primary choices of the works of art.

AAN: Thinking about the term ‘Language’ which appears in the exhibition title in a literal sense: Xu himself operates in between two languages – English and Chinese – do you feel this contributes to a tension, negative or otherwise in his work?

Stephen Little: An interesting question, I think the term ‘language’ in the title can be interpreted on several levels. There are of course the two languages – Chinese and English – that Xu employs in his works. Then there are the fictional written languages created by Xu Bing, some aspects of which blend Chinese and English written forms; then there is the language of the philosophical discourse that Xu Bing brings out in his work, which leads the viewer to consider the somewhat arbitrary and changeable nature of language, and the entire history of writing in both China and the West, and the ways in which writing embodies and reflects patterns of human thought, and the ways in which languages and systems of writing change over time.

AAN: In a less literal sense, how is Xu’s ‘language’ different to that of other contemporary Chinese artists? Many contemporary Chinese artists operate within the lexicon of traditional Chinese art, but incorporating a Western artistic language. Can you put your finger on what stands Xu Bing apart?

Stephen Little: Xu Bing deals more directly with language and writing than many of his contemporaries, in that language, writing and the tools for writing are consistent elements in his work. I think the primary way in which Xu Bing stands apart is that he asks ambitious questions of his audience, by bringing to the fore the arbitrary nature of the symbols with which we as humans transcribe speech, and the degree to which these symbols change with time.

Using Chinese to do this is especially useful because Chinese is one of the most monolithic writing systems in world history, having changed very little since the 3rd and 4th centuries (at least since the time of the great calligrapher Wang Xizhi). Xu Bing raises the dialogue about language to a level that transcends any particular culture – in other words, the issues he raises are relevant to any culture that has a system of writing. He thinks easily on a global level, and by asking big questions about writing – questions that themselves shed light on other cultural and human issues (for example, are there anything truly fixed and absolute in any human culture, or is everything subject to change and transformation?). He proves to be an artist of global importance.

AAN: How does Xu Bing continue to engage with traditional Chinese art forms in the exhibition?

Stephen Little: I appreciate the way in which this exhibition explores the fluid boundary between calligraphy and painting in both traditional and contemporary Chinese culture – on both the theoretical and practical levels, an awareness of which is still useful for fully comprehending some of the great accomplishments of contemporary ink painting.

This appears, for example, in his work entitled The Mustard Seed Garden Landscape (2010), a printed scroll inspired by the 17th-century woodblock-printed Painting Manual of the Mustard Seed Garden, which demonstrates different techniques of manipulating the brush to create particular landscape elements – techniques of brushwork that are closely related to those found in traditional Chinese calligraphy.

AAN: Are there political undercurrents to his work?

Stephen Little: I do not detect any particular political undercurrents in his work, which is one reason I think it remains relevant regardless of when and where it was produced.

AAN: How far do you think Xu Bing has managed to transcend cultural boundaries through his work with the written word? Does the exhibition focus exclusively on how language has dealt with these boundaries, or do his Buddhist sympathies play a role? Can religion and language even be separated within his work?

Stephen Little: I think his focus is on bigger, more universal questions and issues. The degree to which Buddhist concepts play a role in his work is visible, for example, in his works in the exhibition that comprise traditionally bound books that have been partially eaten and then wrapped in silk threads by live silkworms: this work is very much about impermanence, a fundamental concept in Buddhism – and I love the way in which the silkworms have both partially destroyed the books (by eating them) in order to create something completely new – and by doing so have transformed the books into objects wrapped in their own ‘cocoons’.

AAN: The installation piece Square Word Calligraphy Classroom allows visitors to practise the ancient art of calligraphy. How important is this interactive aspect to the exhibition? And to Xu Bing’s work in general?

Stephen Little: I am pleased that the exhibition includes this interactive component, so that visitors can practise mastering Xu Bing’s unique calligraphic creations. I also admire the way Xu Bing demystifies his work in this way, and admire his intent in drawing the public into his sphere of creation.

AAN: Xu Bings’s work seems universal, it speaks to a wide and diverse audience. To what extent do you see Xu Bing’s work as a search for his personal identity?

Stephen Little: I actually think Xu Bing is quite grounded in his own identity, which is simultaneously Chinese and global, and in being so grounded does not feel compelled to continually explore and manifest his own identity. He is consequently free to explore bigger issues which speak to everyone.

BY SARAH BOLWELL

The Language of Xu Bing, until 26 July at LACMA, Hammer Building, Los Angeles, www.lacma.org