IN THE CENTURY and a half that has passed since Utagawa Hiroshige’s death, his name has become synonymous with ukiyo-e print-making, to which he devoted his life. The Meiji Restoration of 1868 – a mere decade after Hiroshige’s demise – marked the start of a period of protracted upheaval in Japan, with the collapse of the long-standing feudal shogunate and the end of Japan’s isolationist foreign policy of sakoku.

The scope of Hiroshige’s influence was able to spread into the West as a result, and his print style contributed to the Japonisme movement in Europe in the late 19th century; the work of Impressionist painters and, later, Cubist artists drew on the flatness and vivid colours of the ukiyo-e print-makers in their own work.

Many of Hiroshige’s prints were directly imitated by artists outside Japan, Whistler, Manet and Van Gogh among them. His local influence was also keenly felt; his work, his artistic successors believed, encapsulated the beauty and excitement of the so-called ‘floating world’.

Early Life of Utagawa Hiroshige

Utagawa Hiroshige was born under the name of Ando Tokutaro in 1797. His father, a fire warden of samurai stock, and his mother died within a year of each other when he was twelve, leaving a duty to protect Edo castle from fire to the orphaned Ando.

At fourteen, Ando became a pupil of the celebrated ukiyo-e artist Utagawa Yoyahiro, and from there his infatuation with the world of print-making developed. Working under the newly-acquired name of Hiroshige, he began to depict the subjects upon which the floating world artists focused: the bijin-ga (courtesans) and yakusha-e (actors), who sought celebrity in the entertainment district in Edo. Hiroshige eventually gave up these figure prints in favour of the landscapes for which he found fame, and in this change of subject he was influenced by his contemporary and fellow ukiyo-e master Hokusai Katsushika.

Travelling Along the Tokaido Highway

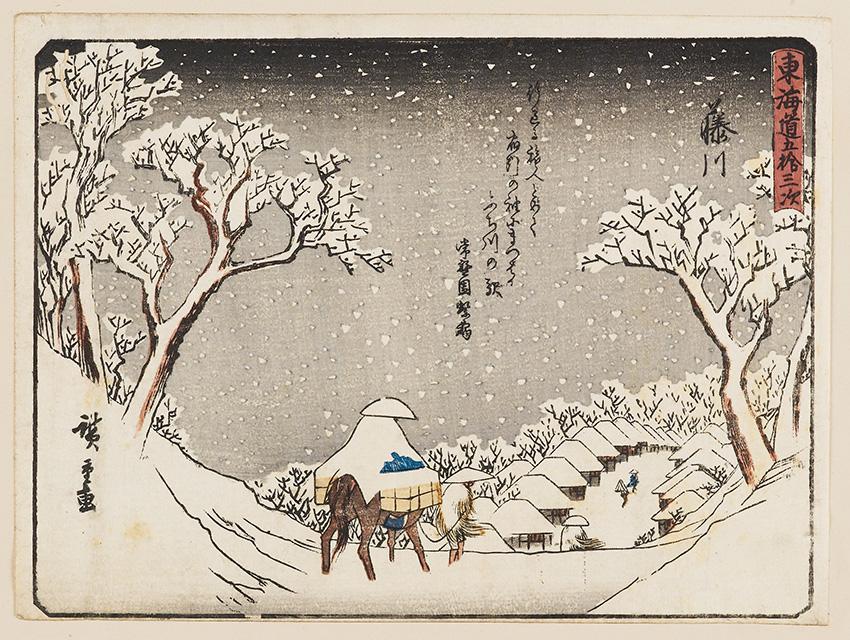

In 1832, Hiroshige travelled along the Tokaido highway between Edo and Kyoto, resting at the fifty-three stations which lined the road. This journey became the basis of his series the Fifty-Three Stations of the Tokaido Road, a collection of 55 landscape prints for which Hiroshige has long since been celebrated.

In this collection of prints, Hiroshige vividly depicts the route along Honshu’s eastern coastline, down which endless crowds of itinerant merchants, pilgrims, artisans and daimyo travelled from Edo to Kyoto. The series – a move away from subject-focused woodblock prints – followed Hokusai’s illustrious Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji in contributing to the burgeoning ukiyo-e style of meisho (famous views).

Hiroshige continued to make his landscape prints, developing an idiosyncratic focus on the power of nature in his work; the human figures who inhabit his scenes are often unclearly visualised, victims of the raging weather systems which occupy most of the frame (his Sudden Shower Over Shin-Ohashi Bridge and Atake being a famous example).

Experimenting with Vertical Landscapes

Towards the end of his life, Hiroshige began to experiment with vertical landscapes, producing his celebrated Sixty-Nine Stations of the Kiso Kaido, and One Hundred Famous Views of Edo. He died of cholera in the epidemic of 1858.

Only a few years later the Meiji era began and a long-standing separatist nation saw its rebirth as a place of industry and international trade. The agrarian, shogunate society Hiroshige had immortalised in his prints rapidly became a thing of the past, and, as a result, his work and that of his contemporaries was cherished as being emblematic of a bygone Japan.

His impact is clear in his home country; the mantle of his name and methods was taken up by his son-in-law, the self-styled Hiroshige II, while his meisho series found a modern successor in the work of Koyabashi Kiyochika and – in his lively re-imagining of the Tokaido highway – Munakata Shiko.

Japanese Prints Infiltrate the West

Elsewhere, the prints of Hiroshige and Hokusai were collected by wealthy enthusiasts of Japonisme, and began to infiltrate the European Impressionistic consciousness. Amsterdam’s Van Gogh Gallery currently plays host to the artist’s striking Japonaiserie: Flowering Plum Tree (after Hiroshige) and Bridge in the Rain (after Hiroshige), both imitations of prints included in Hiroshige’s One Hundred Famous Views of Edo. In a letter to his son written in 1893, Camille Pissarro famously observes that ‘Hiroshige is a marvellous Impressionist. Monet, Rodin and I are full of enthusiasm …’.

Enthusiasm for Hiroshige’s Prints Continues

Decades later, public enthusiasm for Hirsohige continues to endure. In acknowledgement of his unrelenting popularity, the Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology is exhibiting his Fifty-three Stations of the Tokaido Road until 15 February, the first in a series that the museum will display to highlight the significance of Hiroshige in Japan and beyond.

Clare Pollard, curator of Japanese Art at the Ashmolean, attests to the continued import of Hiroshige’s work, noting that Hiroshige’s ‘Skill at capturing the effects of weather, season and light, his striking compositions and his often humorous depictions of people going about their everyday business give his designs a universal appeal that is as powerful today as it was to the Japanese print-buying public in the mid-1800s or to Western artists and Japan enthusiasts a few decades later at the time of Japonisme.’

The Prints on Display

The prints on display at the museum – principally designs from the Hoeido Tokaido, which Hiroshige created in the early 1830s for the publisher Hoeido, although also comprising such later prints as the Kyoka Tokaido of 1840-42 and the Upright Tokaido of 1855 – are taken from the Ashmolean’s abundant archive of Japanese art.

The museum’s collection of Japanese woodblock prints as a whole, Pollard explains, ‘covers the period from the origins of the ukiyo-e style in the late 17th century up until the late 19th century, but is particularly rich in the work of Hiroshige.’

Utagawa Hiroshige’s Prints in the Ashmolean’s Archive

The Hiroshige prints in its archive come largely from the collection of Japanese prints that was formed in the early 20th century by a collector called Herbert Jennings, of Kew, Pollard says, and were donated by a Mr and Mrs H Spalding, who acquired it from Jennings’ daughter, Mrs Evelyn Allan.

Following this exhibition of the Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō Road, the Ashmolean will continue its focus on Hiroshige and his portrayal of floating world-era Japan with further displays of his prints, including his famous views of Mount Fuji and several Japanese provinces. The series, which has been organised to coincide with a new catalogue of Hiroshige landscape prints in the Ashmolean’s collection, is a clear and timely testament to the artist’s lasting international popularity.

Landscape, Cityscape: Hiroshige Woodblock Prints in the Ashmolean Museum by Clare Pollard and Mitsuko Ito Watanabe is the catalogue published to accompany the exhibition and explores Hiroshige’s landscape prints and his unusual compositions, which include humorous depictions of people involved in everyday activities in wonderful detail as well as masterly expressions of weather, light and the seasons.

It also illustrates and discusses over 50 Utagawa Hiroshige landscape prints in the collection of the museum’s collection and explores their historical background, and also gives a concise introduction to Hiroshige’s life and career within the context of Japan’s booming 19th-century woodblock-print industry and explores the development of the landscape print as a new genre in this period. It also discusses and illustrates the process and techniques of traditional Japanese woodblock print-making. Available for purchase from the museum’s website at £15.

BY XENOBE PURVIS

Until 15 February ,at the Ashmolean Museum, Beaumont Street, Oxford, www.ashmolean.org. On 24 February, the Ashmolean will be presenting in their tea house The Art of the Japanese Tea Ceremony. Free, but booking is essential.