THE BRITISH MUSEUM is an encyclopaedic museum dedicated to human history and culture and is known for exhibiting artefacts from ancient cultures. It is perhaps less well known that the museum also displays and collects the works of living artists. They are addressing this by an exhibition featuring artists from The Stars Group.

Clarissa von Spee is a curator at the British Museum for the Chinese and Central Asian collections that range in date from the 6th to the 21st centuries. Like many of her colleagues, she is convinced that the display of modern and contemporary art together with traditional and ancient works provides new context and adds a broader dimension in perceiving and understanding them.

In 2010, Dr von Spee presented Book from the Sky (circa 1988) by Xu Bing in her exhibition, The Printed Image in China from the 8th to the 21st Centuries, and in 2012, displayed Dictionary (2009) by Liu Dan in the show, Modern Chinese Ink Painting. This autumn, the British Museum presents seven selected works by two members of the former ‘Stars’ group from the museum’s collection by Qu Leilei (b 1951) and Ma Desheng (b. 1952), which is on show from 1 November to 15 December, 2015.

Who Were The Stars Group?

Asian Art Newspaper: Who were the Stars Group?

Clarissa von Spee: The Stars were a disparate group of artists and writers who came together informally to form China’s first avant-garde movement in Beijing around 1979. A core group of five artists included Qu Leilei and Ma Desheng, as well as Wang Keping, Huang Rui and Yan Li, who were also active in the underground literary movement.

Early on, they were joined by the female artist, Li Shuang, and the writer, Zhong Acheng. The artist Ai Weiwei (b 1957) joined later, when the group was more formally established. The Stars had chosen their name rather spontaneously which set them apart from the cult around Mao who represented the sun that outshines everybody else. According to Ma Desheng, ‘every artist is a star’ who shines individually; the point the group wanted to make was to encourage individuality and diversity in artistic expression.

AAN: Is there any reason why Qu Leilei and Ma Desheng’s works are being shown at the British Museum at this particular time?

CvS: This autumn season is an ideal moment to display the museum’s works by Qu and Ma, which will complement and juxtapose a display in November of the British Museum’s most famous Chinese painting, Admonitions of the Instructress to the Court Ladies, traditionally attributed to the court artist Gu Kaizhi (circa 344-406). In addition, the exhibition coincides with a retrospective of Ai Weiwei’s work at the Royal Academy, as well as the annual Asian Art in London event.

Chinese Avant-garde Art

AAN: What was the nature of avant-garde art as espoused by the Stars Group?

CvS: The Stars were hardly a unified artistic group. They were a loose collection of individuals, and their art was very diverse. Although many of them were involved in underground poetry and literary work during the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976) and had formed circles of literary friends, their existence as an art group lasted for only a few years from around 1979 to the early 1980s.

There were also other unofficial art groups active in the underground during the still repressive late years of the Cultural Revolution. However, it was the Stars who eventually created works of art that aroused international attention. And by presenting the greatest diversity of content and form, they broke the ground for the later 1985 New Wave art movement.

AAN: How and when did the Stars Group make their first public appearance?

CvS: During this time, Deng Xiaoping sought to solidify his power base through a relatively tolerant policy and setting it apart from the Mao era and the turmoil of the Cultural Revolution. At the same time, the artists of the Stars were seeking greater public exposure.

The ‘Beijing Spring’ in 1979

They saw a brief period of cultural openness called the ‘Beijing Spring’ in early 1979 as offering an opportunity – and made an official appeal to exhibit their works at the National Art Gallery of China in Beijing. It was denied. The Stars responded by staging a provocative event on 27 September 1979: They hung some 120 works overnight on a fence outside the gallery’s premises which marked their first public appearance as a group.

AAN: What were these 120 works like?

CvS: They were of diverse media and in part expressed political dissent. Two of the most powerful and iconic objects in the open-air display were Wang Keping’s small wooden sculptures: Silent being the head of a human being whose one eye is blinded with a round piece of metal and whose mouth is stoppered; and Torso showing a naked female torso, a work that broke with sexual taboos at the time. Qu Leilei exhibited a whole series of drawings, and Ma Desheng showed monochrome woodcuts; among them his print, The People’s Cry, of which we have an impression in the museum’s collection.

AAN: What was the official, as well as public reaction to this event?

CvS: The event aroused immediate public attention. The Beijing authorities and the international press were quick to respond. On the third day of the exhibition, the works were taken off display and temporarily confiscated. The closing of the exhibit provoked the Stars into organising a protest march on 1st October, 1979, the 30th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China.

The Protest March

AAN: What happened during the protest march, a potentially dangerous thing to do, and what transpired afterwards?

CvS: Ma Desheng led demonstrators from Beijing’s Democracy Wall to the government offices while Qu Leilei and others carried banners calling for artistic freedom, diversity and individuality. When they set out for demonstration on the morning of 1 October, they were aware that it could result in their arrest.

In another incident two weeks later Qu, who worked for China Central Television, was assigned lighting duty for the trial of the democracy activist and writer, Wei Jingsheng. Operating clandestinely, Qu placed his bag with a hidden tape recorder next to the audio speakers. He managed to hand the recording over to Wei’s fellow activists after the trial – its proceedings were immediately printed, posted on the Democracy Wall and given to foreign journalists.

Fortunately, Qu Leilei escaped punishment, but his political reliability was always questioned since the incident. In the event, The Stars were allowed to resume their spontaneously staged exhibition. It took place at Huafangzhai in Beijing’s Beihai Park from 23 November to 2 December the same year and attracted thousands of visitors.

AAN: What happened to The Stars Group subsequent to this show?

CvS: They had another very successful exhibition in 1980, this time inside the National Art Gallery of China itself. But in the years following the ‘Beijing Spring’ the political climate changed. The Stars and their works were officially condemned, and most of their members left China. Ai Weiwei left for the United States in 1981; Qu Leilei moved to England in 1985 and Ma Desheng went initially to Switzerland before settling in France in 1986.

Qu Leilei and Ma Desheng

AAN: How have Qu and Ma developed their work once outside of China?

CvS: Today Qu Leilei and Ma Desheng are internationally recognised artists who maintain studios in London and Paris, respectively. Despite a booming market and the temptation to commercialise their art, their spirits are still driven by the endeavour to find creative approaches that express a universal concern for humanity and the needs for freedom of the individual within society. Both Qu and Ma have worked with diverse media of paper and ink, stone and oil on canvas. Moreover, Qu is known for his calligraphy and Ma for his poetry and for directing performances on video.

AAN: What is so distinctive about Ma Desheng’s works in the British Museum’s collection?

CvS: The British Museum has a group of 30 early black-and-white woodcut prints that Ma created in the aftermath of the Cultural Revolution. These were the critical years between 1979 and 1981, when Deng Xiaoping propagated economic and social reforms and implemented his Open Door policy, allowing artists to explore new subject matter and new ways of individual expression.

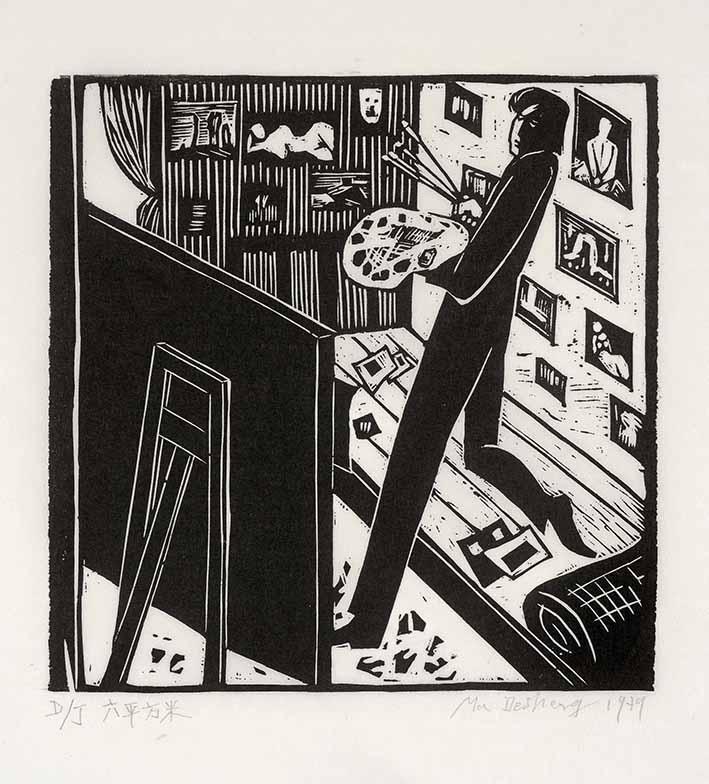

On display are a selection of prints of each year from 1979 to 1981 documenting how Ma’s artistic interests shifted in subject matter – from those reflecting the living conditions of the time and the call for freedom of expression, to more abstract forms.

AAN: Can you provide details of some of Ma’s works made in 1979?

CvS: One entitled, Six Square Metres shows the artist leaning on his bed while working on a painting – an image of his studio that served both as a working and living space. Stylistically, Ma pays reference to the Belgian printmaker Frans Masereel (1889-1972), who inspired Chinese artists of the earlier Modern Woodcut Movement of the 1930s.

The same year, Ma made The People’s Cry, featuring hands raised in an expressive gesture towards the sky. Another print depicts a pair of black and white cats visualising with a sense of humour, Deng Xiaoping’s famous pragmatic expression of 1961: ‘It does not matter if a cat is black or white, as long as it catches mice’.

AAN: Ma’s work in 1981 appears somewhat different, perhaps a little abstract?

CvS: A print of 1981 shows some rounded stones below a horizon arranged like a group of human figures engaged in communication. The figures appear to turn towards a distant shore, evoking the association of this composition with the artists and intellectuals that began to leave China in the 1980s.

It documents Ma’s increasing interest in experimenting with abstract forms, and anticipates his later works in real stone and those that feature in his current oil paintings. In fact his prints mark an important stage in his artistic career as a member of the Stars whose activities revolved around and peaked in the years 1979 to 1981.

AAN: How different are Qu Leilei’s works that are being presented in the British Museum’s show?

CvS: Qu Leilei’s Lei Feng, a monumental ink painting executed in 2012, is part of a series called Empire. It merges the image of Mao’s hero, Lei Feng, a 20th century soldier of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army with the body of a 3rd-century BC, Qin-dynasty terracotta warrior.

In 1963, the ‘Learn from Lei Feng’ campaign had presented Lei as a role model and icon of selfless and patriotic devotion to party and country. According to Qu Leilei, the fusion of both iconic figures, conveys the idea that even after 2000 years, Chinese political ideology has hardly changed. Both figures had to serve like screws within the state’s system, submitting their individual needs to the state’s overriding goals. In this context, Confucianism contributes also to the restraints of human and individual desires by putting the state first in a hierarchically structured society.

What is the Meaning of the Work Journey?

AAN: What is the meaning of Qu’s work entitled Journey?

CvS: Journey, from 2013 is part of another series called, Facing the Future. Here Qu explores the potential of the human hand as a motif to express human relationships, affection, and communication. The painting features the hands of two individuals held together. Although they do not reveal gender, race, or age, they express a universally understood gesture of trust, sympathy and consensus.

The illuminated hands set against the dark void create a contrast of light and shadow inspired by marble sculptures. Technically, Qu Leilei explores the use of the traditional Chinese media of brush, ink and xuan ricepaper in combination with a creative play of light and shadow – comparable perhaps to black and white photography or the modelling of sculpture.

The Admonitions Scroll Alongside Ma and Qu’s Work

AAN: Why is the British Museum’s Admonitions Scroll being displayed in the same space as Ma and Qu’s works?

CvS: Contemporary art is not created in isolation. It is a response to the spirit of the time and is created in a context that includes biographical, cultural and historical aspects of the past. Qu Leilei’s critical stance towards Confucianism, as expressed in Lei Feng, is being complemented by the Admonitions Scroll intended originally to advise ladies at court in correct Confucian behaviour.

The Confucian system expected women to submit to their roles as wives and mothers of multiple offspring in order to assure a harmonious society and a functioning state. In that respect the Admonitions Scroll illustrates how society and state were supposed to function. Qu Leilei depicts another protagonist of the Confucian state system, a terracotta soldier of the First Emperor’s army. However, by fusing the ancient soldier with the modern one, he provokes the viewer to question what holds them together.

AAN: What is the overall intention of this autumn show including The Stars Group?

CvS: Our display of Ma Desheng and Qu Leilei’s works demonstrates their engagement with the former Chinese as well as the current international art scene. While the artists of the 85’ New Wave movement tend to dominate the art market and attract the attention of the public, the show looks back at those artists who were active a decade earlier and in fact, created the conditions for China’s new contemporary art scene.

Over the years, Ma Desheng and Qu Leilei have become good friends of the British Museum. For many years, Qu has been involved in our public programmes. During the exhibition held in Room 91a, they offer a special insight into their work and creativity; and discuss their lives and experiences as artists, in China and Europe, in a public conversation.

BY YVONNE TAN

This display is at The British Museum, London, from 1 November to 15 December, 2015.