The Chinese paintings currently conserved in Japanese collections reflect more than a thousand years of connoisseurship in that country. A primary source material, they offer contextual information about the nature of their transmission from China to Japan. They tell us the circumstances surrounding collecting in Japan since mediaeval times and offer insights into changing patterns of taste and patronage. As works of Chinese artists outside of China, particularly those no longer found in their homeland, they serve as valuable historical documents through which scholarship might be advanced. A selection of these works from the Ichikawa Beian Collection is now the subject of an exhibition curated by Mr Tsukamoto at the Tokyo National Museum’s newly reopened Toyokan, ‘Asian Gallery’.

‘The earliest Chinese paintings in Japanese collections date from at least the Nara period (710-794) as cultural relics transmitted from Tang China (618-906),’ says Tsukamoto Maromitsu, Assistant Curator of Asian Art, Curatorial Research Department at the Tokyo National Museum. ‘When monks introduced Zen Buddhism to Kamakura Japan (1185-1333), temples became repositories of Southern Song (1127-1279) religious paintings.

Private collections were formed in the Muromachi era (1336-1573). The Ashikaga shoguns, Yoshimitsu (1358-1408) and Yoshinori (1394-1441) collected exquisite literati paintings from the Southern Song academy and the Yuan (1279-1368), classified as So-Genga, ‘Song and Yuan paintings’, a continuum not differentiated by dynastic category as they are in China.

The tea ceremony had its roots in Muromachi Japan. Since the shogun Yoshimasa’s (1436-1490) connoisseurship extended to tea ceremony works, the Ashikaga holding was named Higashiyama gomotsu, ‘collection of Lord Higashiyama’ after him. Japan now has famous collections collected by dynasty. However, Chinese paintings brought to late Edo period Japan (1615-1868) had a distinctive flavour.’

Governing Japan was the Tokugawa bakufu, ‘shogunate’, a military dictatorship. It regarded its duty, as a secular authority ruling the entire country for the first time, to promote ethical teaching. Confucianism was chosen as the ruling creed and brought about an important revival of classical Chinese studies. Their guiding principles created a desire for karamono, ‘things Chinese’, such as paintings and ceramics, coveted by shoguns and daimyo, ‘feudal lords’ alike.

By the 18th century, following the return of peace, the capital Edo and other cities had grown rapidly. Their relative affluence and the circulation of money led to the flowering of a new urban middle class, among whose literary circles, intellectual and artistic pursuits took pride of place. Collecting and connoisseurship previously limited to shogun and daimyo, thus became a privilege also enjoyed by the literati.

Prominent 19th-century literatus Ichikawa Beian’s (1779-1858) collection is now the subject of an exhibition at the Tokyo National Museum. Born in Edo, the son of Ichikawa Kansai, who headed the Shoheiko, the official Confucian academy, Beian was a scholar and specialist on Chinese writing. He admired Northern Song (960-1127) court artist, Mi Fu’s (1052-1107) calligraphy, identified as the formal ‘scholar-official’ style, and adopted the Mi ideogram for his artistic name. In 1799, he established his calligraphy academy, Shozanrindo, ‘Hall of Forested Hill’ at Izumibashi, Edo.

Espousing a personal style called Beian ryu, he was later known together with Maki Ryoko (1777-1843) and Nukina Kaioku (1778-1863), as the bakumatsu sanpitsu, ‘three brushes of late Tokugawa Japan’. During his lifetime, Beian assembled almost 1,000 works of painting, calligraphic and epigraphic material. In 1848, he catalogued 260 objects in his Shozanrindo shoga bunbo zuroku, ‘Illustrated Catalogue of Chinese Calligraphy, Painting and Stationery from the Shozanrindo Collection’.

Each entry was accompanied by assiduous notes punctured with details about material, dimensions and means of acquisition. Beian’s biographical anecdotes and personal annotations about subject matter and style give the catalogue – a valuable document today – a highly individual and spirited character, mirroring the idiosyncracies of a late Edo period connoisseur.

Beian died a decade before the advent of Meiji Japan (1868-1912), when modernisation and ‘Westernisation’ saw new institutional collectors entering the fray. Fearing a dilution of its traditional culture, the authorities established museums to preserve Japanese and Asian art in the country. The earliest, the Museum of the Ministry of Education, was founded in Tokyo in 1872. Four years later – although Beian’s collection had been dispersed – his grandson,

Santei donated 38 works from the Confucian Shoheiko, to the museum. Upon its renaming as the Tokyo Imperial Household Museum in 1900, Beian’s son, Sanken contributed 41 objects. These works initiated what is now the Tokyo National Museum’s Chinese collection, renowned as the largest repository of the art of China outside of the Chinese world.

Throughout its history, Japan has provided occasional refuge for Chinese of various complexions. Among those fleeing Manchu rule in the mid-17th century were Ming (1368-1644) loyalists and monks of the Obaku Zen sect. They conveyed, far more than the valuable Chinese heirlooms, paintings, scholarly and religious texts that they carried, new and timely, information about Ming material culture to Tokugawa Japan.

The Obaku monks introduced a new and less formal, tea ceremony based on sencha ‘fermented’ tea and its culture of Ming literati paintings. Besides, they practised the karayo, ‘Chinese style’ calligraphy, encouraging personal expression by writers and poets of their own artistic sensibilities. It flourished in mid- and late Edo Japan and appealed directly to Beian’s instincts; the ‘running’ style of Fujian Ming artist, Wang Jianzhong being a favourite.

Until Beian’s lifetime, there was limited access in Japan to Chinese paintings, reference to which came mainly from illustrations in printed and model books. His assemblage of Ming and Qing (1644-1911) landscapes, floral, vegetal and figural subjects and calligraphy was dependent on resources available at the time. They reflect the spirit, approach and ultimately, the values of 19th-century Japanese connois-seurship. Some works from Fujian and Zhejiang are rare or little known, and have no equivalent in China. Their significance lies in their place in Japanese art history and their contributions to the development to Edo period painting.

In China, there are few works by Mu Tan (dates unknown) of the Ming. The 17th-century Chrysanthemum and Bamboo attributed to him, focuses ostensibly on the chrysanthemum and the bamboo, symbols of moral rectitude. The subject matter however is not its pictorial component. It is the text alluding to famous Tang poet, Du Fu’s (712-770) sentiments about losing his homeland after being devastated by the An Lushan Rebellion of 755.

He played a prominent role in Muromachi literature, and was popular with Edo period Confucian literati. The reference to Du Fu was interpreted by Beian as indicating Mu Tan’s sorrow at losing China to Mongol rule, since he was ‘really a Yuan dynasty scholar’ who preferred to leave the Ming Hongwu (r.1368-1398) era work undated. ‘It has yet to be ascertained if Beian’s analysis is correct,’ says Mr Tsukamoto. ‘Still, it is to his credit that he investigated a work so thoroughly. Beian was a samurai at heart, to whom loyalty to one’s homeland was of paramount importance. His choice of any painting was dependent not on style alone, but also on the artist’s moral and social fibre.’

Another Ming work from the Ichikawa Beian Collection, Flowers attributed to Lu Zhi (1496-1576) in the 44th year of the Ming Jiajing (r.1522-1566) era is questionable. Beian read it as a flower painting Lu executed after visiting Zhixing Mountain. ‘Understanding Ming literature has helped us identify paintings. Today, this would not be considered an authentic Lu Zhi work,’ says Mr Tsukamoto. ‘But whether it is real or not is immaterial, because it was chosen by a 19th century mind.’

In 1804, the first year of the Bunka era (1804-1818), Beian ventured south to Nagasaki where a parting gift from the Shinagawa family, the Miaosha jing sutra,became one of his most treasured possessions. He construed the sutra text, written in Yan style ‘regular script’ calligraphy in gold on indigo paper, as coming from the hand of Shenzong, the Ming Wanli (r.1573-1620) emperor.

It made a deep impact on Beian who copied it frequently. ‘Sutra calligraphy has not been given its due and is not usually appreciated – as compared to other genres – to be a form of high art,’ says Mr Tsukamoto. ‘It was not the custom however, for the emperor to engage in writing sutras – a task normally consigned to a daibi, ‘scribe in attendance’.’ Nevertheless, the sutra is a specimen of what circulated in 19th-century Nagasaki and an emblem of its close and enduring contact with Chinese culture.

In the 17th century, Edo Japan’s opening encounters with the West had been less than desirable. After expelling the Portuguese in 1638, it embarked on two centuries of self-imposed isolation. Only the Dutch were allowed to trade under strict terms at Deshima island in Nagasaki Bay. The shogunate thus relied on Chinese sources for information about the outside world, and a regular approved trade between the two countries, came by way of Nagasaki. It became synonymous with Chinese culture as a refuge for émigrés, among them the 18th-century artist, Chen Nanpin – hardly known in China – whose ‘Nagasaki realist’ style had eminent disciples such as Kumashiro Yuhi, So Shiseki and Kinoshita Itsuun.

In 1826, the ninth year of the Bunsei era (1818-1830), Beian travelled to the imperial capital, Kyoto where his friend, Fukui Shin collected works stylistically similar to Lohan, in gold on indigo paper. Beian thought the work ‘did not resemble Japanese painting’ but had ‘curious Qing-type characteristics’ which were ascribed to Qing Jiaqing’s (r.1796-1820) time. He subsequently discovered that Vietnam, then known as Annam, also boasted a Jiaqing emperor (r.1059-1065) of the Ly dynasty, and concluded that this was a Vietnamese painting of circa 1087, contemporaneous with the Northern Song. And this attribution added became an interesting addition to Ichikawa Beian Collection

‘It is clearly a Qing-dynasty work, and no current scholar would draw these conclusions,’ says Mr Tsukamoto. ‘However Beian’s findings should not be dismissed. These paintings circulated neither in Japan nor China before the 18th century; it is reasonable to confuse them with Vietnamese work.’ Paintings of Annamese origin reached Japan only when trade expanded after Hoi An’s port opened in the 1600s. They were often misattributed to China because the variants to ‘Chinese’ painting were better known.

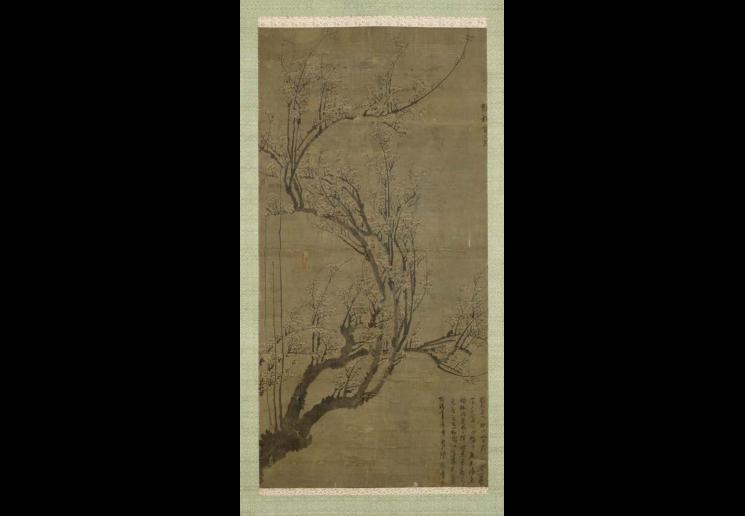

In Kyoto, Beian had acquired Plum Blossoms by Chen Lu, a classical composition dated 1446, the eleventh year of the Ming Zhengtong (r.1436-1449) era. It features the plum, a symbol of courage that defies winter by flowering early in the ‘blossoming branch’ style. In Edo, Beian showed it to a friend, Oda Hyakkoku who ‘having seen the painting some 13 years before at Kagoshima, cannot believe it is now in Beian’s hands’.

Apart from Nagasaki, Chinese paintings were known to circulate in the then Satsuma domain of Kagoshima, Kyushu. Its Chinese connections, particularly with Fujian, came through Okinawa, the main island in the Ryukyu archipelago, a vassal from 1609 to 1879. Known as Liuqiu in Chinese, the islands had enjoyed formal tributary relations with Ming China already from the 1370s.

When the Ashikaga shogunate ceased direct Ming trade in 1523, Okinawa emerged an intermediary and remained anxious even under Satsuma control, to maintain its Chinese ties. Meiji Japan annexed Okinawa afterwards and made it a Japanese prefecture after 1879. This painting, in the Ichikawa Beian Collection, testifies to longstanding maritime links between Japan and China, which Beian catalogued under shimamono, ‘island things’.

Today, the Ichikawa Beian Collection collection is one of the best conserved and most complete of the Tokyo National Museum’s 19th-century Chinese collections. Despite some limitations, it is essential to understanding the nature, character and passage of artworks to Edo Japan. In the 20th century, however, there was an appreciable shift in connoisseurship when Japanese collectors embarked on direct dealings with China.

The Kansai industrialists, Takashima Kikujiro (1875-1969), Aoyama San’u (1912-1993) and Hayashi Munetake (1923-2006) for instance, professed a new taste for Northern Song, Yuan and literati paintings in the orthodox style. After the war, when they donated their collections to the museum, the quality, range and complexion of its holdings reached exceptional levels.

BY YVONNE TAN

The Ichikawa Beian Collection: An Exhibition of Paintings, Calligraphy and Stationery is at the Toyokan, Room 8, Tokyo National Museum, 13-9 Ueno Park, Taito-ku, Tokyo 110-8712, until 23 September, www.tnm.jp