Asian Art Newspaper looks at early Islamic silk textiles in this exhibition organised by the Cleveland Museum of Art.

‘NOW COME with me and cast your eye over the immense crowd of turbaned heads, wrapped in countless folds of the whitest silk, and bright raiment of every kind and hue, and everywhere the brilliance of gold, silver, purple, silk and satin… A more beautiful spectacle was never presented to my gaze.’ – So wrote the 16th-century European Busbecq, clearly impressed by a royal Ottoman ceremony attended by myriads of dignitaries clad in silk court costume.

At the pivot of Islam, the Ka’ba in Mecca is covered with the kiswa, a silken veil, now black but formerly in many colours. According to mediaeval poets it is covered ‘like a bride’; and poetry composed for the walls of Granada’s Alhambra Palace celebrated silk textiles thus: ‘I am (like) a bride in her nuptial attire endowed with beauty and perfection’.

Another poem, also written at the time of Islamic rule over Andalucia, compares brocaded silks to the aesthetic glory of the Hall of Two Sisters: ‘With how many a decoration have you clothed it… which causes the brocades of Yemen to be forgotten’. The Persian 11th-century traveller Nasir-I Khusrau had written of Sana’a’ that ‘her striped coats, stuffs of silk and embroideries have the greatest reputation’.

Islamic Silk Textiles Were Treasured Items

Silk textiles have been one of the most coveted and treasured items in the arsenal of Islamic decorative arts from the earliest Mongol association with silk as an indispensable symbol of status, wealth and power, to its sensuous apogee of luxury and finesse at the Ottoman court. This exhibition in Cleveland, Luxuriance: Silks from Islamic Lands 1250-1900, displays the Cleveland Museum of Art’s world-class collection of Islamic silk textiles, demonstrating their provenance from Granada to Mughal India.

As an art form par excellence, silk had many practical and philosophical functions, as well as providing visual and tactile pleasure. Silk textiles were a crucial form of liquidity, thanks to their high value and portability. Emirs, emperors, caliphs and sultans, the foremost consumers, gave silk textiles and clothes as diplomatic gifts. They were also a part of political propaganda functioning as walking advertisements on the backs of courtiers bearing laudatory inscriptions, naturally emblazoned with the name of the ruler.

Islamic silk textiles also played a pivotal role in architecture, transforming spaces by partitioning, curtaining off private areas, draping key features such as entrances, and of course functioning as mural decorations. Some silks were pictorial, others more abstract. They were taken to the West because they were often used to wrap Christian relics, preserved as church treasures and incorporated into ecclesiastical vestments.

From China Over the Silk Roads

Silk thread originally travelled westwards from China over the Silk Roads. But its high cost and the smuggling out of the secrets of sericulture – the cultivation of silkworms and production of raw silk – ensured development of workshops and weaving techniques, initially in Persia. Silk thread is derived from secretions of silkworms (Bombyx mori), which produce long, strong filaments accepting dyes well.

In the 6th century, the Sasanians started using drawlooms to weave silk, whose great advantage is their ability to repeat patterns mechanically on lengths of cloth. Two artisans are involved, the first inserting wefts horizontally, the second using a figure harness for the warp to activate the design vertically.

Drawlooms had originated in China, whose imagery, such as dragons, phoenixes, lotus and peony blossoms, cloud and wave formations continued to influence design for centuries. However, in the 7th and 8th centuries medallion silks from Persia and Soghdiana were exported eastwards to Tang China and Japan.

Production Blossomed as a Result of the Mongol Invasion

A glorious era of Islamic silk textile production blossomed as a result of Mongol invasion, although Ghengis Khan is not usually associated with aesthetic proclivities. The initial impact on urban life was catastrophic, but as the descendants of Khan became established, they adopted many of the court customs of the cultures they had displaced. The Mongol regime swept through and ruled most of Asia from 1206-1368, evolving from a culture without a weaving tradition astonishingly to one creating opulent cloths of gold called nasij, and other luxury silks, initially as symbols of their dominance and legitimacy, then as robes of honour and also for ceremonial tents.

They forcibly resettled both Islamic and Chinese artisans, including textile designers and weavers, producing an eclectic, multi-cultural variety of imagery and techniques, including a fluid, asymmetrical style. An increasingly rich textile trade resulted, drawing foreign merchants from Syria, Egypt, Venice – and even China.

Islamic Silk Textile Weavers

Islamic silk textile weavers are renowned for their textiles of lampas, velvet, seraser, and ikat. Lampas, called kemha during the lengthy Ottoman period, (1281-1924) was developed by Iranian weavers in the 11th century and adopted across Europe and Asia. It resembles damask and was often used for upholstery. Usually twill weave dominates a satin weave background, producing highly detailed designs.

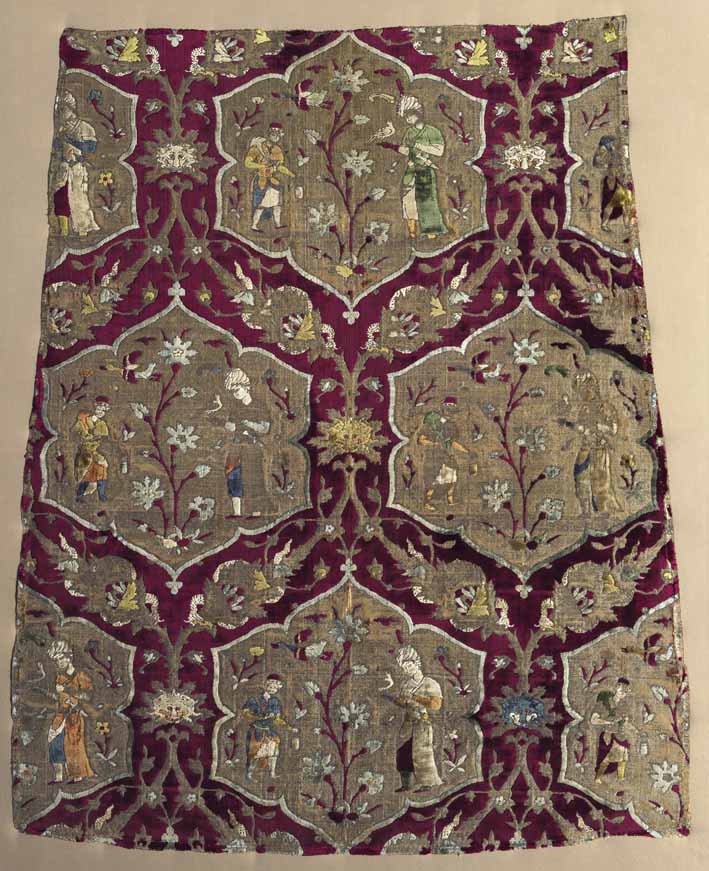

Iranian Silk Velvet

Iranians again initiated silk velvet, this time in the 13th century. Often beneath the pile warp (vertical), voided weft (horizontal) areas were brocaded with metallic thread. Cut-pile silk velvet was known as Kadife during the Ottoman Empire; their artisans also developing a complex technique called seraser of interlaced weaving used for cloths of gold or silver, often of great originality and even eccentricity.

Ikat Fabrics

Ikat fabrics, very fashionable nowadays, were created in silk in Central Asia, though they have a rich pedigree in many other parts of the world. The name ‘ikat’ is derived from the Indonesian/Malay word mengikat. It means to tie or bind, since ikat is a resist process like batik, in which materials like impermeable thread are used during the process of dying to repel the dye in chosen areas.

Successive immersions in different dyebaths can result in sophisticated Ikats of seven or more colours. When the dying is complete, the cloth is mounted on the beams of a loom, separated into upper and lower layers, which during weaving are opened and closed, creating the design.

Islamic Silk Textiles During the Mamluk Dynasty

When the Mamluk dynasty of Egypt and Syria (1250-1517) defeated the Mongols, artisans fled south from Iran and Iraq, bringing with them their skill at silk weaving on large drawlooms to Cairo, the centre of Islamic culture of the era. In fact the largest body of late medieval Islamic silk textiles are those from Mamluk Egypt. Fine examples were used as a mark of rank or office, a different one hung behind the seat of each member of the council of state.

Promotion within the hierarchy was often rewarded by the gift of a whole set of silk garments, and elaborate ceremonies involved a complete change from silk cap to silk slippers. Two striped caps in the exhibition from the 1300s are of quilted lampas featuring animals of the hunt alternating with inscriptions citing the caliph of the time.

A brocaded Mamluk silk with extensive gold thread, circa 1430, was sent to Spain, where it became a mantle for a statue of the Virgin; another to Italy where it clothed the Madonna in a painting. Europe also provided an eager market for silk damasks, first woven at Damascus. Many textile names derive from their Eastern origins, such as muslin from Mosul in Iraq.

But despite constant demand for their sophisticated silks, towards the end of the dynasty Spanish, Italian and Chinese craftsmen, who copied Mamluk textiles closely, were undercutting their weavers. So despite its high international status, the Mamluk silk weaving industry suffered irreversible decline.

Islamic Silk Textiles in Spain

Meanwhile, almost eight centuries of Islamic rule in Spain, from 711-1492, had established thriving sericulture centres, like Malaga’s numerous mulberry groves feeding silk worms. Initially tiraz factories operated in Seville and Cordoba processing the silk, then in the 12th century, Almeira became the centre of the Spanish silk textile industry. One of the Cleveland Museum’s great treasures, the Alhambra Palace silk curtain, was woven in the imperial textile workshop there during the Nasrid period, one of the two largest, most magnificent curtain-hangings to have survived from the 1300s.

Its restrained style and minimalist motifs echo the decorative patterns of the exquisitely delicate stuccowork of the Alhambra. As Louise Mackie, Curator of Textiles & Islamic Studies at Cleveland Museum, comments: ‘The entire pattern is formed with surprisingly few motifs: leaves, interlacings and inscriptions… Leaves form medallions, arcades and continuous vines known as arabesques. Arabic inscriptions are rendered in angular Kufic script… or in cursive Nakshi script’.

The visual repertoire of other silk textiles of Islamic Spain is far more elaborate, featuring fabulous beasts such as double-headed eagles, griffins, sphinxes and even harpies. Their other-worldliness was intended as an idealised symbol of majesty, though some motifs evoke royal power much more explicitly, such as an eagle seizing its prey. With the expulsion of Muslims and Jews from Granada in 1492, many craftsmen moved to Morocco, where their skills were valued and they were able to work in their customary style. Moroccan silk brocades became status furnishing fabrics for the Ottoman Empire.

In Safavid Iran

The French traveller Tavernier noted that in Safavid Iran there were more people engaged in silk-weaving than in any other trade. In Kashan ‘one single city quarter boasts of one thousand houses of silk workers’, according to fellow-countryman Chardin. Clearly the earlier Persian pre-eminence in silk textile production had resurrected during the Safavid dynasty of 1501-1722.

Under the visionary leadership of Shah ‘Abbas I (reigned 1587-1629), his capital Isfahan became the leading centre of silk textile production, though factories were established by royal command all over the realm, notably at Yazd and Kashan. Chardin also commented on the huge amount produced of shorn velvets and reversible brocades, some embroidered with gold or silver thread, saying: ‘They last forever’. So these Islamic silk textiles survive in impressive quantity, often with innovative designs, since each centre was encouraged to ‘weave in its own manner’.

However, Shah Abbas was careful to monopolise the lucrative sericulture industry, encouraging the export of raw silk to Europe, as well as finished products. An entire room in Denmark’s Rosenborg Castle is hung with them.

Fascinatingly, for the most part, there is an absence of political iconography in their themes. The designs echo delicate, vivid Persian book illustrations, almost all of human figures and often of the pleasures of court life with its dancers and musicians. Lovers dally among blossoming trees, a wine bearer approaches between cypresses, languidly elegant young men wear European clothes, reflecting the cosmopolitan nature of the Safavid regime. In turn, European artistic influence inspired a new simplified semi-naturalistic style including single figures with limited modelling; and around 1600 signed silks appeared for the first time.

Export to Mughal India

But Safavid Iran’s most important export market was Mughal India, founded by its emperor Babur in 1526. An Indian lampas weave canopy dating from the 16th century in the exhibition is remarkably eclectic, drawing on Hindu and Buddhist elements as well as Muslim. Its imagery is unexpected, too – mythical animals such as a green eight-legged creature attacking a yellow hybrid lion.

Such luxurious canopies were essential accoutrements of Mughal rulers as conspicuous symbols of wealth, while providing welcome shade. Mughal India was an avid customer for Ottoman silk textiles, and many merchants, among them Italians and Poles, as well as buyers from Muscovy, frequented Constantinople. Hundreds of bales of Turkish silk were sent to Moscow in part to pay for fur linings for the luxurious garments sent back to warm wealthy Ottomans. Textiles and complete outfits of clothing survive in considerable quantity due to the holdings of the Topkapi Saray, and the fact that Istanbul was never sacked and looted.

On occasions silk was spread along a sultan’s route – the original ‘red carpet’ treatment. In a more mundane context, the word ‘sofa’ is derived from the Ottoman divans covered with brocaded silk lampas or velvet, with matching cushions sometimes embroidered with gold thread. For female garments, embroidery, sometimes of gold thread (zerduz) had a practical function – to cover intimate areas, around which, otherwise, floated diaphanous silk.

Silk Production in Bursa, Turkey

Its production was confined to specialist teams working within the Topkapi. Women in their own homes often produced other types of embroidery. Far to the northwest of Turkey, Bursa was the western terminus of the raw silk trade from the Caspian, and the centre of the silk textile industry from early Ottoman times. Here Iranian raw silk was graded, weighed and taxed, with the bulk shipped to Italy.

Lustre, elasticity and weight affected its grade, the most lustrous reserved for velvet pile. Such was the scale of the silk business, and importance to the economy, that it required government supervision – quality was vital and artisans serving these gigantic state enterprises were in effect civil servants, and had to conform to a ‘house style’. Although Ottoman silk production achieved a pinnacle of excellence, creativity, let alone experimentation, was discouraged. Traditional floral and foliate designs and talismanic chintamani, along with Christian images for export to the Eastern Orthodox Church dominated production can all be found in the Islamic silk textiles of this period.

An International Style Develops and the Ottoman Court

Textile designers, spinners, weavers, producers of metallic thread, tailors and associated silk specialists were organised in guilds, with fixed salaries. Nevertheless, a significant ‘international style’ began to develop, spearheaded by enterprising Italians whose painters depicted their subjects in Ottoman inspired floral patterns. Italian artists were invited to the Ottoman court to paint portraits of sultans and favoured members of their harem.

The Ottoman court artists of course were intrigued, and exposed to the European creative canon, began exporting to contemporary Islamic courts in Mamluk Cairo, Timrod Herat and Turkmen Tabriz. Across Central Asia in countries now called Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan and Afghanistan, dazzling Ikat silks were created during the 19th century, with Bukhara and Shahr-I Sabz, near Samarkand, the principal production centres of Islamic silk textiles. Women wore ikat robes called munisaks for rites of passage throughout their lives, beginning with their weddings with fabric given by the groom’s family, then at festivals, significant family occasions, and finally for their funerals.

BY JULIET HIGHET

Luxuriance: Silks from Islamic Lands 1250-1900 runs until 27 April at the Cleveland Museum of Art, Ohio, www.clevelandart.org. It previews a forthcoming book, Luxury Textiles, 7th-20th Century by Louise Mackie.