When the dance troupe of the Cambodian royal court visited France in July 1906 they inspired Auguste Rodin (1840-1917), one of the greatest sculptors of the 19th century, to create 150 superb drawings in just a few days. Rodin & Dance: The Essence of Movement, a new exhibition at the Courtauld Gallery in London, featuring 23 sculptures and 40 drawings, is the first to explore Rodin’s fascination with dance and bodies in extreme acrobatic poses and this exhibition includes four of his pictures of the Cambodian dancers who caused a sensation in France. Fascinated by the dynamic of physical movement throughout his life, Rodin was instantly enthralled by the graceful gestures of the little dancers and started drawing immediately.

Rodin Rapidly Produced Drawings

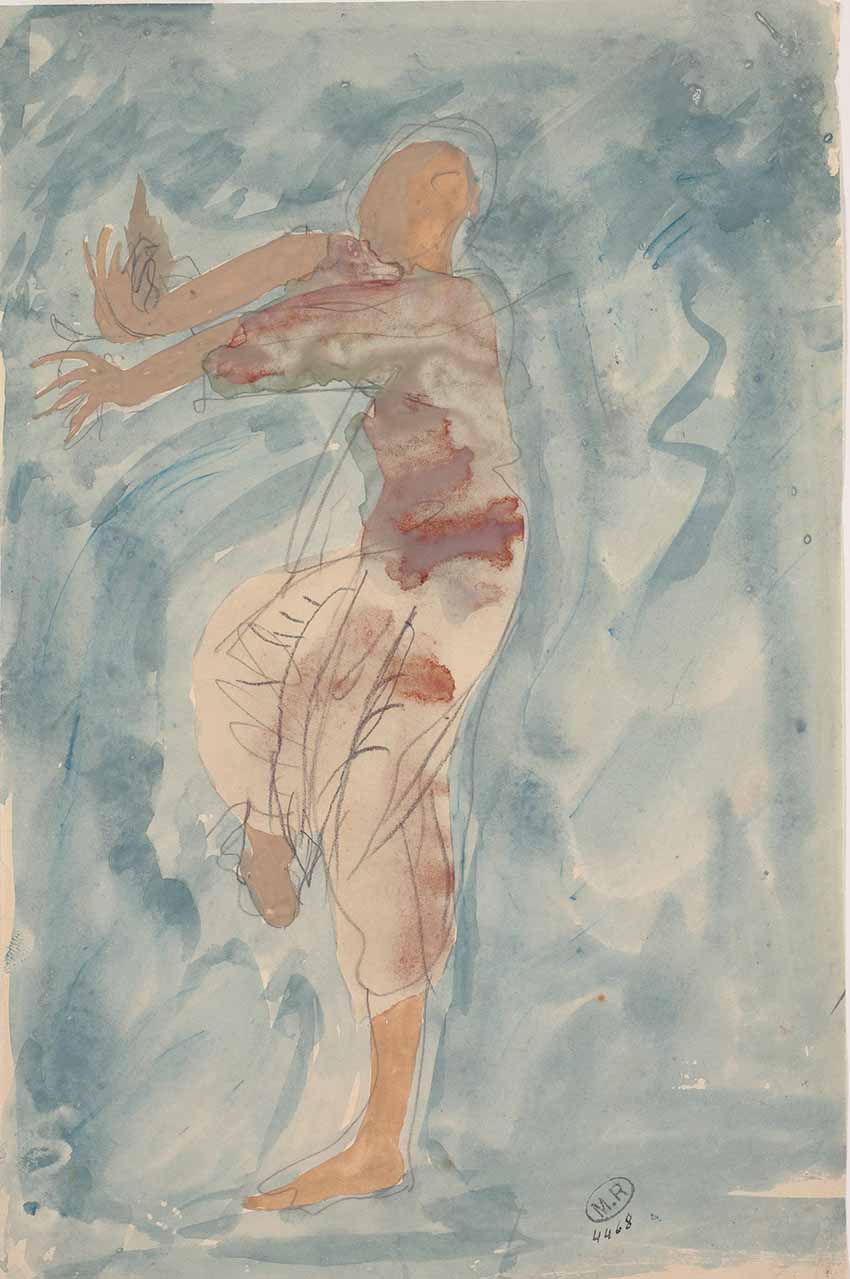

His rapidly produced drawings, later highlighted with watercolour tints, reveal the excitement of this extraordinary encounter between Rodin, then 66 years old, and the exquisite girls of the troupe. ‘I contemplated them in ecstasy …’ he declared of the experience which revitalised his waning artistic genius.

First Visit by a Cambodian Monarch to France

The dancers, accompanying King Sisowath to the Colonial Exhibition in Marseilles, came to Paris to perform at the Pré-Catalan Theatre in the Bois de Boulogne. This was the first visit by a Cambodian monarch to France, which had ruled over Cambodia and Indochina since 1884. The royal ballet, representing their country’s most precious living art, enhanced his presence, and the 42 Cambodian dancers included his daughter, Princess Sumphady.

They performed episodes from the Ramayana, reinterpreted in Khmer as the Reamker, with the stylised gestures of hieratic ballet, with its hypnotic slowness, harking back to the great Khmer empire of 9th to 15th centuries at Angkor where the temple was a recreation of the Hindu cosmos and the dancers embodied its rhythms.

An audience of 3,500 people attended, far more than could be seated, resulting in an atmosphere of excitement. When the troupe appeared, Rodin, an official guest, was captivated. He had never seen such small dancers, like children, barely into their teens. ‘The tiny movements of their agile limbs were strangely and marvellously seductive,’ he claimed and started sketching immediately.

The Friezes of Angkor Came to Life

He was fired with passion for the aesthetics of their movements, so different from Western ballet. ‘I contemplated them in ecstasy …’ he declared. The next day Rodin rushed to the villa where they were staying to do further drawings of the Cambodian dancers. ‘The friezes of Angkor were coming to life before my very eyes,’ he exclaimed. His relationship with them was paternal and he had to bribe them to pose by buying them toys. ‘These divine children who dance for the gods hardly knew how to repay me for the happiness I had given them,’ he said.

Captured Every Nuance of the Dance Patterns

He drew obsessively to capture every nuance of the dance patterns of these Cambodian dancers, concentrating on the arms and the delicate hands, ignoring facial features, his sculptor’s eye seizing on the essence of dance. His drawings are incomparable documentation of the subtle movements, unrecorded except for early photographs.

Rodin, a naturalist intent on expressing emotion and character in sculpture by capturing the intellectual as well as the physical force of his subjects, brought the same emphasis to drawing, through the interplay of light and shadow, moving his pencil continuously, without looking at the paper, to seize every detail of animation. A consummate draughtsman, he produced some 10,000 drawings during his life, 7,000 of which are in the Musée Rodin in Paris.

The Sacred Meaning of Cambodian Dance

He understood immediately the profound sacred meaning of Cambodian dance. Since ancient times, dance and architecture have been regarded as the two most important sacred arts, concerned with the use of space and rhythm. As a symbol of the universal rhythm, dance evolved from the hallowed precinct of the temples to that of the royal court and became a regal ritual, attaining the heights of artistic refinement.

In an art form whose origins are divine, the dancers are a link between the terrestrial and celestial realm. ‘Dance is animated architecture,’ he wrote, comparing the Cambodians to the angel carved on the façade of the Cathedral of Chartres. ‘They have made the antique live in me.’

Followed the Cambodian Dancers Back to Marseilles

He followed the Cambodian dancers back to Marseilles in the train, drawing constantly, and continued until they embarked on their ship home. ‘I contemplated them in ecstasy. When they left … I was in the dark and in the cold, I thought they had taken with them all the beauty of the world.’

Subsequently he also produced small-scale clay figures, a series of nine Dance Movements, in leaping, twisted poses, some of which may have been based on the Cambodians, found in his studio after his death, now on display. The Courtauld exhibition marks 110 years since the drawings of these Cambodian dancers were done, and the first time any have been seen in Britain. They celebrate that brief, intense encounter that propelled Rodin to a new artistic vision as dance became his last, magnificent theme.

BY DENISE HEYWOOD

Until 22 January 2017 at the Courtauld Gallery, Strand, London, www.courtauld.ac.uk

FURTHER INFORMATION ON KHMER/CAMBODIAN DANCE

Classical Cambodian dance (also known as court dance) is Cambodia’s most precious art form. More than 1000 years ago classical dance was established as a bridge between the gods and the kings – the spiritual and the natural world. In the modern era, classical dancers performed for royal rituals as well as privileged visitors to the palace.

In classical dance the movements require a command of techniques, which demand flexibility, accuracy, and control of movements. With fingers curved backwards, an arching spine, bent knees, and toes flexed upwards, the fully grounded dancer moves with precise balance and divine grace.