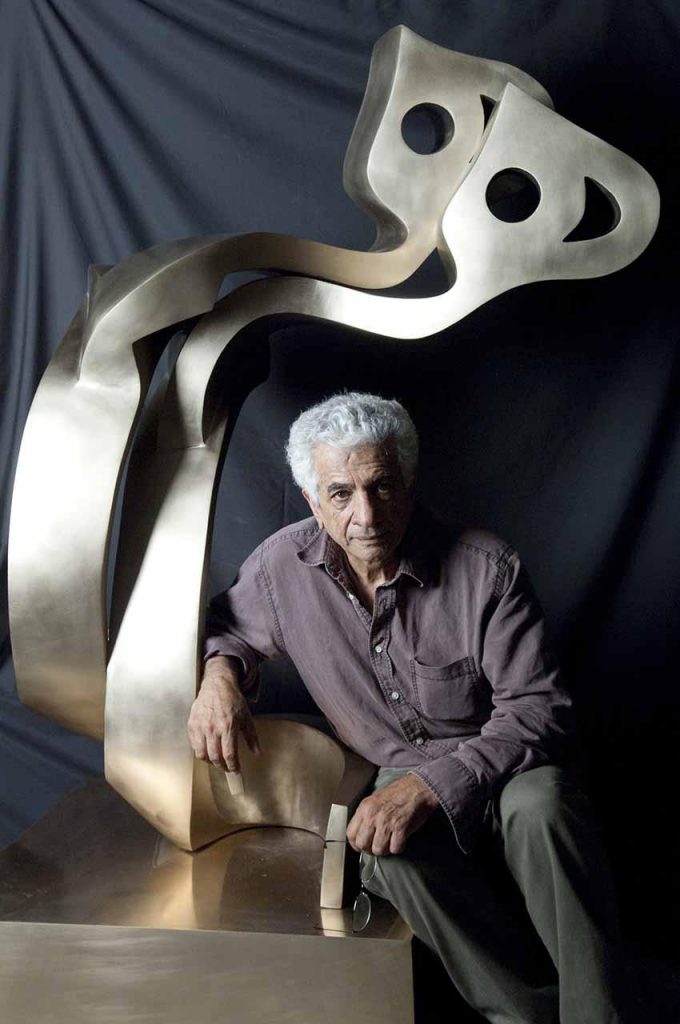

CONTEMPORARY CULTURE in the Middle East is greatly enriched by a phalanx of inspired and inspiring Iranian artists. But in fact, despite the cataclysmic political and social upheaval of the country’s recent history including the Islamic Revolution of 1979, astonishingly an Iranian creative avant-garde has been active for at least 60 years. Parviz Tanavoli, born in 1937, has been a luminary of the Iranian art scene for decades. He is still creating messages of universal resonance, which are visually beautiful, despite or perhaps enhanced by the serious nature of their commentary, such as his opposition to the holding of prisoners in Guantanamo Bay.

Father of Modern Iranian Sculpture

Critically acclaimed as ‘the father of modern Iranian sculpture’, influencing at least two generations of its artists, Tanavoli is internationally acclaimed, with more than 20 solo shows worldwide, the first in 1958. In 2008, his significance in the world art market resounded when he created auction history, breaking the record price for a contemporary Middle Eastern artwork in Dubai, by reaching US$2.8 million for his famous sculpture Wall (Oh Persepolis). (keninstitute.com) Now the first comprehensive retrospective exhibition of his work is being held in a US museum.

Primarily famous as a sculptor working with various materials including brass, copper, scrap metal and particularly cast bronze, his work has been described as ‘poetry in bronze’. He says: ‘I write my poetry on the surface of the sculpture’. But his ever-expanding oeuvre also includes painting, silk-screens, printmaking, ceramics, rugs and jewellery. Most recently, he has been creating sculpture with day-glow neon tubes. Furthermore, over the long course of his career, he has become highly regarded as a scholar, writer, teacher and collector.

Graduated from the Tehran School of Fine Arts

Having graduated from the Tehran School of Fine Arts in 1956, this master continued his studies in Italy, in Carrara and Milan, after which he taught sculpture for three years at the Minneapolis College of Art & Design.

Then he returned to Iran, to direct the sculpture department at the University of Tehran, a position he held for 18 years until 1979 retiring to concentrate on the art which has earned him inclusion in some of the world’s leading art collections, such as the Museum of Modern Art, New York and the British Museum. Before the Islamic Revolution, Tanavoli was cultural advisor to Farah Pahlavi, former Queen of Iran.

The Saqqakhaneh Group

A remarkable and unusual blend of traditional and modern aesthetics characterises most Iranian contemporary art. In the late 1950s and early 1960s Tanavoli, as a pioneer of many art initiatives, was one of the founders of the highly influential Saqqakhaneh group, which continues to inspire Iranian art today.

It was a neo-traditional movement that drew inspiration from the rich cultural heritage of Iran, seeking to reintegrate and reinterpret traditions such as calligraphy and classical poetry. It was named after the popular Tehran street shrines in the form of drinking fountains that commemorate the martyrs of Karbala. Saqqakhaneh drew on other Shia Muslim symbols, folklore and on popular art.

In fact it was often referred to as the ‘School of Spiritual Pop Art.’ Kamran Diba makes a fascinating comment: ‘There is a parallel between Saqqakhaneh and Pop Art, if we simplify Pop Art as an art movement which looks at the symbols and tools of a mass consumer society as a relevant and interesting cultural force. Saqqakhaneh looked at the inner beliefs and popular symbols that were part of the religion and culture of Iran, and perhaps, consumed in the same ways as industrial products in the West’.

Although the essence of Saqqakhaneh was to reconcile the aesthetics of heritage and modernity, many of its artists created Modernist images, in terms of design and colour reference to Western Modernism, which Tanavoli eventually rejected as what he considered too much of a reliance on Western art influence.

Iranian Poetry and Literature

Crucial to understanding the key inspirations for Tanavoli’s work, it is necessary to appreciate not only his involvement with the lyrical heritage of Iranian poetry and literature, but also his exploration of historic architectural ornament, local design, vernacular crafts and folklore. He has written numerous books and articles on subjects which include tombstones, jewellery, textiles, lion rugs, kilims, Shahsavan scissor bags, and on apparently utilitarian objects such as horse and camel trappings, salt bags, bird cages, scales and weights, chairs, walls and locks, several of which appear as symbols and recurring motifs in his work – lions and lattice-work grilles, for instance, along with hands, birds, and above all – walls and locks.

Persian padlocks are among the earliest in history, produced in unexpected shapes like birds and animals, pots and bowls. With a large collection of these locks, Tanavoli published a book recording them, and dismantling and repairing them became a favourite pastime. Naturally, this gave him a thorough understanding of their construction, and he began producing a series of lock-inspired sculptures.

Locks Embellish Walls in Tanavoli’s Work

Sometimes locks embellish walls in his work, resulting in a monumental series of bronzes, The Walls of Iran, inspired by the pre-Islamic sculptor Farhad the Mountain Carver, and which represent some of the sculptor’s greatest achievements. With Tanavoli’s vision – walls, which are intrinsically enclosing devices and barriers – become symbols of refinement and evolution, in part due to the ‘universal’ script he inscribes on their surfaces.

This intricate script apparently refers to Sumerian, or Egyptian, hieroglyphics, but it’s also evocative of even more ancient ‘writing’ – Cuneiform, as well as Aramaic, Armenian and Persian. Furthermore, it refers to the highly decorative Islamic calligraphy developed creatively by several of Tanavoli’s contemporaries. As he said: ‘I write my poetry on the surface of the sculpture’.

A Recurrent Theme is Poets

Another recurrent theme of Tanavoli’s work is ‘poets’. In Islam, but particularly in Sufism, with its mystical aspects, poets are regarded as embodiments of piety. Poets such as Jalal al-Din Rumi, Omar Khayyam, Hafez and Sa’adi propose that love for a human being is representative of love for God. ‘Happy the moment when we are seated in the palace, Thou and I, with two forms and two figures but with one soul. Thou and I.’ Couplet from Rumi’s Divani Shamsi Tabriz.

Parviz Tanavoli’s Heech Sculptures

At the centre of the current Davis Museum exhibition is a garden of Tanavoli’s Heech sculptures, the series for which he is most famous. Initiated in 1965, the heech concept and body of work now celebrates its 50th anniversary. For Tanavoli, in both physical and symbolic ways, heech is a return to the very essence of his culture, the concept of the oneness of a human being and God, the pinnacle of the Sufi path.

Parviz Tanavoli’s sculpture Heech Lovers epitomises this concept – gently and fluidly the lovers are entwined, representing hope, promise and potentially unlimited possibilities, rather than unbending isolation. Another masterpiece of the series, a double heech titled The Loving Heech, is to a Sufi, (or anyone else), an even greater symbol of the human spirit eternally intertwining with the essence of God, the lovers perpetually in accord.

Heech is a fascinating concept on every level. Literally in Farsi it is composed of three letters, starting with the Arabic ha, Symbolically, it represents nothingness. But as Tanavoli explains: ‘Heech is not nothing. It has a body, a shape, but also a meaning behind It’. The ha for Sufis represents God, for nothingness is considered as an aspect of the divine, and for Islamic numerologists ha is the letter of guidance.

A secular parallel in Western philosophy is the number zero: both whole but empty; everything and nothing. Ultimately the notion of nothingness and the replacement of the small self or ego in favour of the Inner or Higher Self is a universal concept.

Parviz Tanavoli’s Heech series has had multiple expressions interpreted in a variety of materials, from miniature masterpieces of jewellery to monumental bronzes, and latterly – hi-gloss fibreglass and neon tubes. In the bronze Heech in a Cage of 2006, the heech symbol escapes or is liberated from its enclosing cage-like structures, representative of the grilles surrounding Iranian street shrines. Tanavoli has said that another of his masterpieces, the 2005 Caged Heech, directly refers to the prisoners who continue to be detained at the infamous Guantanamo Bay Prison, often without trial for many years.

Settled in Canada

Since 1989, 10 years after the Islamic Revolution, Parviz Tanavoli and his family decided to settle in Canada. However, today he divides his time and engagement between Vancouver and Tehran, with studios in both cities, and an ongoing teaching practice, in which he continues to inspire another generation of Iranian artists. It is staged over 4,000 sq, ft of gallery space and includes signature works from the 1950s onwards, with seven monumental new pieces contributed by Tavanoli, never before exhibited.

The show opens with ‘Early Works’, and a special section devoted to the sculptural series The Walls, as Parviz Tanavoli says, inspired by ‘Farhad, the Mountain Carver’, a continuing catalyst. Another section features sculptures representing significant leitmotifs such as ‘The Poet’, Birds and Locks. A more intimate gallery presents sculpted jewellery, early ceramics, small paintings on manuscript leaves, prints, works on paper and oil paintings on canvas.

Then, occupying centre-stage, this major retrospective of the work of arguably the most major Iranian artist for several centuries, presents a collection of Heech sculptures, triumphantly commanded by an 11-foot stainless-steel masterpiece. Indeed, we have a master in our midst.

BY JULIET HIGHET

Parvis Tanavoli, until 7 June 2015, at the Davis Museum, Wellesley College,106 Central St, Wellesley, Massachusetts, www.wellesley.edu/davismuseum