ON THE Nalanda Trail: Buddhism in India, China & Southeast Asia, a new exhibition about the diffusion of Buddhism in Asia, opened at Singapore’s Asian Civilisations Museum last November. Despite having been put together in a little under a year, the show is undoubtedly one of the museum’s most ambitious art historical endeavors to date. Curated by the institution’s own Gauri Parimoo Krishnan, Senior Curator South Asian & Research, the exhibition is not huge in scale, but nonetheless achieves the juxtaposition of a lucidly didactic narrative approach with the display of objects of superlative artistic quality.

Two Important Stele

Though Nalanda as a beacon of wisdom pivotal to Buddhism’s gradual conquest of Asia is the show’s central theme, On the Nalanda Trail opens chronologically presenting several iconic and superb examples of very early Buddhist art. The star here is the exquisite and even-in-India-unique inscribed 2nd-century BC, Sunga period sandstone relief depicting an empty throne under the Bodhi tree (Buddhist art remained aniconic until the first century) from the Indian Museum, Kolkata.

A second equally significant sandstone stele, contemporary to the latter or slightly earlier, from the National Museum, New Delhi, shows the earliest known representation of Naga Muchalinda, the multi-headed snake emblem. The sculpture is of particular relevance in the context of this comparative exhibition because Naga Muchalinda figures so prominently in Southeast Asian Buddhist iconography. This exemplary pair sets the tone of the show which brims over with objects that are seldom if ever allowed out of their respective state collections.

Important Works Borrowed from International Collections

Indeed, beyond its scholarship, the exhibition is testament to both Dr. Krishnan and the Asian Civilisations Museum’s international credibility, put to the test by the requirement of so much loan material. Says Dr. Krishnan ‘The international support for this show has been remarkable. We have been very lucky to secure so many text-book pieces from the Indian collections, including numerous fragile and light sensitive works such as the priceless Dunhuang paintings that never leave their home institutions, never mind the country. Important pieces have also been borrowed from the Indonesian and Dutch national collections as well as the Chinese University of Hong Kong. And finally private collectors of various nationalities have been especially generous, lending a number of the exhibition’s most significant works.

Nalanda University – Buddhist Pilgrimage

The premise of the exhibition is a comparison of Buddhist works of art from Subcontinental Asia, China and Southeast Asia, with Nalanda explored as a key place of pilgrimage and exchange for scholars and the faithful arriving from the furthest reaches of Asia. Nalanda, located in modern India’s Northern Bihar state, was for many centuries home to the Subcontinent’s most distinguished and ancient place of Buddhist teaching, known as Nalanda University.

Though the monastic centre was established around the time of Buddha, in the 5th century BC, it is the Nalanda of nearly a millennium later, until the 13th century, that is the focus here. Using the material evidence of Indian Buddhist missionaries who left their homeland to travel around Asia disseminating the word of Buddha, as well as the writings and depictions of foreign pilgrims who visited India in quest of first-hand knowledge of the new faith and its philosophy, the exhibition shows the trail of Buddhist learning, the adaptation of its tenets as its practitioners moved away from its original geographic centre, and the evolving aesthetics of its material representation, radiating in all directions across continental and insular Asia, East, North and South.

Buddhism’s Spread to North and Central Asia

The first part of the exhibition more specifically examines Buddhism’s spread to North and Central Asia, the relationship between India and China given particular attention. Through historical writings we know of the Chinese pilgrims Faxian, Yijing and Xuanzang who at different times, from the 4th to the 8th century, traveled to India in search of the true word in the form of scriptures as well as the material incarnation of Buddhism in the form of representations of Buddhist deities.

Xuanzang and Yijing are recorded to have spent several years in Nalanda, respectively toward the middle and second third of the 7th century. Examples of educated monastic non-Indians who travelled to India with the purpose of bringing the Buddhist canon and its artistic incarnation back to their respective lands, these monks returned home with hundreds of Buddhist sutras, which they then translated from the Sanskrit in order to disseminate the doctrine in China where Buddhism, though already implanted, was not always practised in an orthodox and disciplined manner.

Buddhist Influence in Asia

An eclectic, intelligently selected and always artistically excellent array of frequently iconic works of art illuminates this aspect of the exhibition, Krishnan proposing various types of material evidence of Buddhism’s influence and path from the religion’s birthplace in Northern India to Nepal, Tibet, China via the Silk Road, and further East still to Japan.

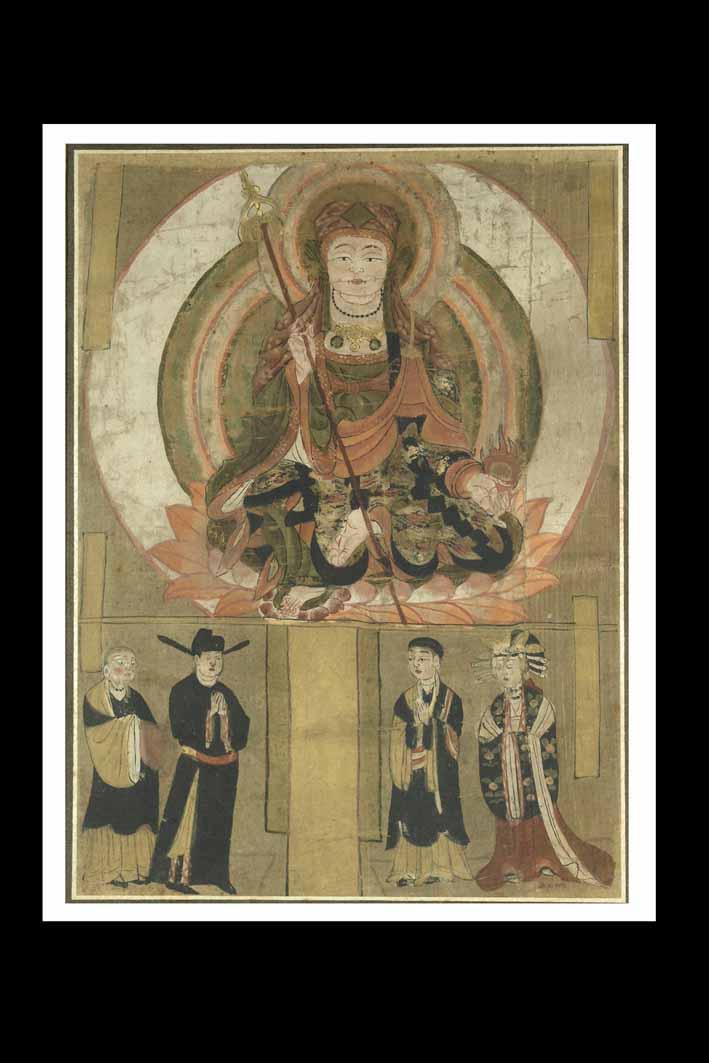

Keen to give her audience a comprehensive understanding of the significance of Buddhism on the move, the curator chooses not only outstanding works of sculptural and graphic Buddhist art, but also manuscripts, coinage and utilitarian objects as source documents. Noteworthy exhibits in this section of the show are numerous and include a wonderfully conserved Tang dynasty Saddharma Pundarika Sutra from Dunhuang, kept in the collection of the Chinese University of Hong Kong Art Museum, an Eastern Wei limestone stele of Buddha, Maitreya and Avlokiteshvara from the Asian Civilisations Museum’s own holdings that combines Indian iconography with local Chinese facial features and clothing style, and a dynamically carved 8th century stone figure of a Dvarapala from the Christopher James Frape collection that displays all the vigour of the high Tang period in tandem with Mahayana’s predilection for a wider selection of Buddhist deities.

Pilgrim’s Bottle Used on the Silk Road

A crisply molded 4th-5th century lotus-adorned terracotta pilgrim’s bottle used on the Silk Route and housed in the National Museum, New Delhi, shows too how the most pedestrian objects can provide clues to the place of Buddhism in everyday life as its practitioners took to the road. But perhaps the most artistically striking pieces from this part of the exhibition are the examples of Gandhara sculpture.

A 3rd-4th century stucco head of well-over-life size proportion from a private collection presents all the sensitivity and naturalism of the classical Greco-Roman style that characterises Gandhara, while an impressive and well-conserved full-figure stone image of standing Maitreya of a century earlier, loaned by Subhash Kapoor, combines non-Indian ornaments and dress with multiple Buddhist emblems at the headdress and base. Finally, a real treat, several rare and beautifully preserved paintings on silk from Tang period Dunhuang, conserved in the National Museum, New Delhi and notorious for never before having been allowed out of India, are featured, splendidly highlighting Buddhism’s Chinese expression.

Indian and Southeast Asian Buddhist Artistic Expression

Buddhism’s trail of knowledge and transformation through India on to Central and North Asia has been much explored. But where Dr. Krishnan treads new art historical ground is in her elucidation of the two-way circulation of ideas and stylistic references colouring Indian and Southeast Asian Buddhist artistic expression.

Working, amongst others, with the huge wealth and seldom travelled Indonesian national collection stored in Jakarta’s Museum Nasional, she underscores the relationship between the artistic expression of Indian Buddhism and that of Srivijaya. Relatively little researched and understood for lack of archeological and other material evidence, the maritime Kingdom of Srivijaya, only first tentatively identified in 1918 by French historian George Coedes of the Ecole francaise d’Extreme Orient, is now known to have flourished on Sumatra from the 7th to the 14th century.

Kingdom of Sriviyaya and other Southeast Asian Kingdoms

Holding sway from the 7th century over Java and much of the Malay Peninsula, rather than a far-flung outpost of Buddhism, Srivijaya was in itself a centre, and as a stronghold of Vajrayana Buddhism, as well as sending its own people to Nalanda, the Kingdom drew pilgrims and scholars from other parts of Asia. These included the previously-discussed Chinese monk Yijing who made several visits to Sumatra on his way to study at Nalanda in the course of the 7th century and would presumably have taken Srivijayan artistic forms, thoroughly indigenous despite their Indian references, back to India with him.

Here the visual documentation supporting the two-way India-Southeast Asia connection is considerably sparser than in the exhibition’s first part. This imbalance, due largely to space and time constraints, may yet be remedied with the addition of Khmer, Burmese and Thai references if the show expands and travels beyond Singapore. But this is not to say that what is offered at ACM is not compelling.

Though not a work of art, the dated 9th century Sanskrit inscribed copper plaque that substantiates the close bilateral relationship enjoyed by the Indian kings of the Pala period and the king of Suvarna Dvipa (present-day Sumatra) is invaluable in its recording of the Indian-Srivijaya linkage and Srivijaya’s financial support of Buddhist monasteries in India around the time of the kingdom’s apotheosis. Found at Nalanda in 1916 and now housed in the National Museum, New Delhi, the plaque is a key find for historians researching Srivijaya.

Though the objects it presents are fewer, important aesthetic and stylistic comparisons are drawn in this section. East Indian, South Indian and Sri Lankan statuary is shown in tandem with Javanese and Sumatran examples, so highlighting the stylistic links between the Indian and Southeast Asian. Similarly, the displays show the stone carving and refined bronze casting techniques of the Nalanda masters of the 7th to 12th century century to have infiltrated the artistic vernacular of Southeast Asian. An 8th-9th century bronze torso of Maitreya from Palembang South Sumatra and housed in in the Museum Nasional, though indigenous in overal feeling, clearly references Nalanda in the stylistic traits of its headgear and facial features.

Through the combined display of extraodinary works of art and a skillfully structured story line, On the Nalanda Trail: Buddhism in India, China & Southeast Asia explores the complex history of the dissemination of Buddhism through China and Southeast Asia. But beyond the narrative’s historical focus on the spread of one of the great world religions, and the breathtaking beauty of its art as it evolved to mirror the faith’s changing cultural environment, this show speaks of the dynamics of exchange, and the culture of tolerance and synchretism that still characterise many parts of Asia today.

BY IOLA LENZI

Asian Civilisations Museum, Singapore, until 23 March. A catalogue accompanies the exhibition.