Korean Fashion at the Textile Museum in Washington DC includes rare examples of clothing worn at the Korean royal court during the late Joseon dynasty (1392-1910), as well as tracing the history of current street fashion seen today around the world. Some of the older embroidered silk jackets and robes on show, as well as furnishings, were originally on display in the Korean pavilion at the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893.

The evolution of Korean fashion and textile arts over the last 125 years is explored through some 85 objects plus digital displays and K-pop videos that introduce textile arts – from hanbok traditional Korean clothing) to home furnishings – and explore how their design and craftsmanship have changed alongside Korea’s profound socio-economic transformation.

Joseon-dynasty Clothes

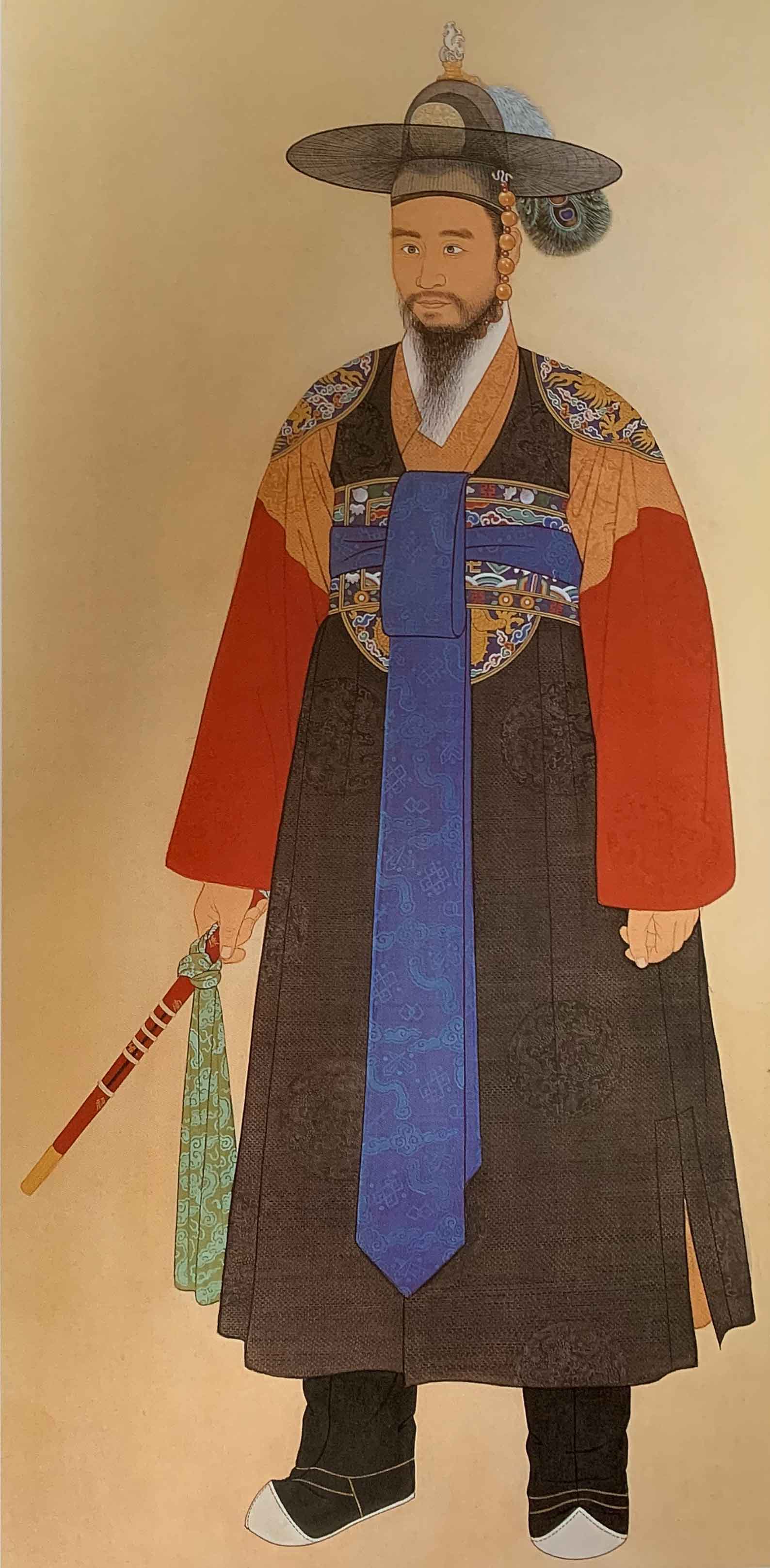

During the Joseon dynasty both women and men’s clothes were strictly regulated and subject to a dress code for each social class. For men at the Neo-Confucian court, the royal family, courtiers, scholars, soldiers, priests, officials and administrators were easily identifiable by their clothes. Colours or robes were influenced by their function – formal or informal – with civil and military officials wearing official robes (cho bok) for morning meetings and other ceremonies. Blue robes were worn inside and red ones for outside. In the 19th century, danryeong (robes with rounded collars) were worn as part of the everyday uniform by government officials and were worn over jikryeongpo (inner robes with straight collars). The fabric used also showed the rank of the official, for example, brocaded silks with patterns of clouds and auspicious motifs would only have been worn by high-ranking administrators.

The military uniform (kun bok) consisted of hats with a peacock feather and tied with a broad embroidered waistband with their rank identified by the decorations worn on their wide-brimmed hat. At court, it was rank badges that indicated class and rank. The Joseon court adopted an insignia system in the mid-15th century to display the ranks of officials. Worn on the front (hyung) and back (bae) of costumes, hyungbae, or rank badges, served as decorative status markers in a society that prized strict hierarchies. Initially permitted only for civil and military officials of the third rank and higher, their use was eventually broadened to all nine ranks. Unlike in China, wives of officials never wore a badge the equivalent of their husband’s rank.

Korean Rank Badges

Various animals were used to designate rank, and the motifs evolved over the course of the Joseon dynasty. In 1871, the insignia were standardized to tigers for military officials and cranes for civil officials. With the introduction of Western Culture to Korea in the 19th century, traditional clothing became simpler and Western-style clothing began to be work in public.

In Korea, an important part of the bridal costume is the hwarot – a heavily embroidered cloak worn over many other layers of clothing. Initially reserved for use by women of the aristocratic and literati classes, by the early 20th century the costume became the standard clothes for all brides. A typical cloak is decorated with multiple auspicious symbols to bring wealth, good fortune, and fertility to the new couple. These expensive robes were passed from bride to bride over many generations. It was standard practice to cover the cuffs and collar with soft paper that could be replaced after each wedding to keep the robe looking fresh.

In the decades following the Korean War (1950-1953), South Korea transformed from an agrarian nation into an industrialized economic powerhouse. Continuing into the modern era, Korean Fashion showcases the work of pioneering Korean designers such as Nora Noh (b. 1928) in the 1950s and 60s, and Lee Young Hee (1936-2018) and Icinoo (b 1941) in the 90s, the first Korean designers to present their collections on Paris runways.

Contemporary Korean Fashion

Digital displays in Korean Fashion invite visitors to explore current street styles, as well as K-pop videos featuring looks worn by some of South Korea’s biggest stars. In the wake of the tremendous success of K-pop, K-cinema and other popular culture products, South Korea has become Asia’s epicentre of new ‘street fashion’. Simplified versions of hanbok have become increasingly fashionable among young Koreans, and the work of designers such as Hwang Leesle (b 1987) and Kim Young Jin (b 1971), who have launched successful brands specialising in easy-to-wear interpretations of historical styles, are on display in the show.

Korean Fashion shows how – in stark contrast to Korea’s earlier centuries of isolation – today’s young Koreans imaginatively intermingle global and local trends, brands and cultural references to create unique statements of identity that often challenge longstanding Korean conventions of dress and behaviour.

Korean Fashion/Korean textiles, until 22 December, The Textile Museum, George Washington University, Washington DC, gwu.edu