LOOKING AROUND the rich interiors of almost any of the palaces or grand houses of Europe, one invariably spots Chinese or Japanese porcelain objects that had originally been imported during the 17th and 18th centuries. Not that many it seems were actually used for much other than decoration, but this was a time when the taste of the élite dictated that space was there to be filled and adorned. Here we explore Imari Japanese porcelain made for European Palaces.

Hardly a console-top or chimneypiece escapes and, for example, in the Berlin Royal Prussian Charlottenburg Palace, we see imported ceramics used to fill unused fireplaces, and in one famous room they are mounted on the walls as decorations reaching up to the ceiling, further adorned for good measure with plenty of gold ormolu.

Perceptions of beauty certainly differ widely according to time and place but on seeing all this over-decoration – so at odds with our slightly self-conscious, thought-to-be-Zen-inspired minimalism – we can be excused for thinking that clean lines and empty space were then perhaps considered somehow sinful. Nevertheless there is a fascinating history behind these porcelain wares and the merchants who brought so many of them to Europe during a few decades following the middle of the 1600s.

Ceramics Imported to Europe for Centuries

Glazed ceramics had been imported to Europe from China for centuries through tenuous, mainly Portuguese-controlled trading routes, and the early ones were rare, expensive and much treasured. But by the Wan-Li period (1563-1620) porcelain was being mass-produced at Jingdezhen – a major centre of ceramic production for more than 2,000 years – and exported in large quantities through the powerful Dutch East Indies Company to an eager market in Europe.

Porcelain wares were highly-prized, not only for their brilliant decorative quality, but also as objects of technical wonder as no-one in Europe yet had the know-how to produce them locally. Although a variety of materials can be fired to make white-body ceramics, kaolin clay (formed by the natural degradation of feldspathic granite) is most used to form the glassy, white porcelain we know as ‘china’.

Kao-Ling or Kaolin Clay

The word derives from Kao-Ling (pinyin Gaoling), the large source of white clay located near the Jingdezhen kilns. By firing kaolin clay at a temperature between 1200 and 1400 degrees centigrade, its particles fuse together like glass to make a hard, waterproof ceramic that rings like a bell when lightly struck and lends itself to being decorated with underglaze painting in cobalt blue and/or overglaze coloured enamels.

Towards the midde of the 17th century, China’s export trade with Europe declined as various parts of the country suffered disorder caused mainly by the collapse of the Ming dynasty, the take-over of power by Manchu invaders, and mini-ice-age weather conditions that led to rice-harvest failure and widespread starvation. The Jingdezhen kilns survived, supplying the weakened domestic market as well as catering to Japanese buyers by providing small, freely-made objects known as ko-sometsuke, (old blue-and-white), with sketchy decoration that appealed to ‘tea-taste’, nevertheless the predominant link with Europe – the Dutch East Indies Company – was impelled to look elsewhere for a fresh source of porcelain.

Timing worked brilliantly in the company’s favour. Despite some years of successful trading in Japan, the presence of the Spanish and Portuguese, (always accompanied by Jesuit priests), alarmed the Japanese shogunate who had heard from sources in Mexico and the Philippines that conquest soon followed conversion. They were expelled, and local christians and the remaining foreign priests were given the option of renouncing their faith or suffering what were invariably extremely painful deaths.

Europeans in Japan

The Dutch, like the Venetians in the Eastern Mediterranean, had no such proselytising motives in Japan, being only interested in furthering their business ventures. Such policy stood in their favour with Japanese authority and to the exclusion of all other Westerners, their East Indies Company was allowed to establish a trading base on the small, man-made Dejima Island in Nagasaki Harbour after moving from a previous settlement in Hirado. From this tiny settlement the Dutch enjoyed a trading monopoly in Japan that lasted until 1855. Around the same time, Japanese porcelain manufacture in the Hizen area of North-West Kyushu had been refined to produce attractive wares of high quality and so the move to Nagasaki led to a new and highly profitable export business.

Japanese Ceramic Artists

Although Japanese ceramic artists had been making superb stonewares for a thousand years or so, it was not until the early 17th century that they began to produce the highly fired white-bodied porcelain that had long been mastered in Korea and China. A master-potter named Ri Sampei, brought to Japan after an ill-fated invasion of Korea by the Shogun Hideyoshi, is reputed to have been the first to locate white, kaolin ‘china-clay’ in 1616, near Arita in North Kyushu. His associate co-immigrant Korean potters had also brought the technology for making climbing kilns capable of firing at high temperatures and soon established a number of kilns to make simple white porcelain wares for the local market.

17th-Century Blue and White Wares and Arita Kilns

These early 17th-century blue-and white wares are now much esteemed by Japanese collectors for their artless rustic quality, showing spare decoration hastily sketched in cobalt blue, (then a very rare commodity, imported via indirect routes from Persia and central Asia), and covered with a clear, almost-colourless glaze.

They were often misshapen due to early technical difficulties, but such hurdles were soon surmounted and by the mid-17th century the Arita kilns were producing perfectly-formed and finely-decorated wares not only for the domestic market, but also for the new export trade. Peerless of all, and extremely rare outside Japan, are the wares of the Nabeshima kilns that were made exclusively for the family of the local warlord of the same name and show superb designs reflecting high-level Japanese taste.

Kinrade Underglaze Decoration

However foreign customers in Europe liked colour, in particular that of the porcelain known as Kinrande, with underglaze decoration painted in cobalt blue and rich, overglaze decoration in red and gold enamels. The shapes of traditional Japanese tableware were largely unsuitable for Western use and taste, and the Arita craftsmen quickly learned to make on demand, large chargers, baluster vases, and those ‘barber’s’ dishes – with what appears to be a bite out of the rim – for holding under the chin while being shaved or having one’s beard trimmed.

Having a rich tradition of skilled decoration, the Japanese were able to able to paint subjects and patterns on export porcelains to the delight of their European customers for whom isolated Japan was as exotic as another planet.

Imari Japanese Porcelains

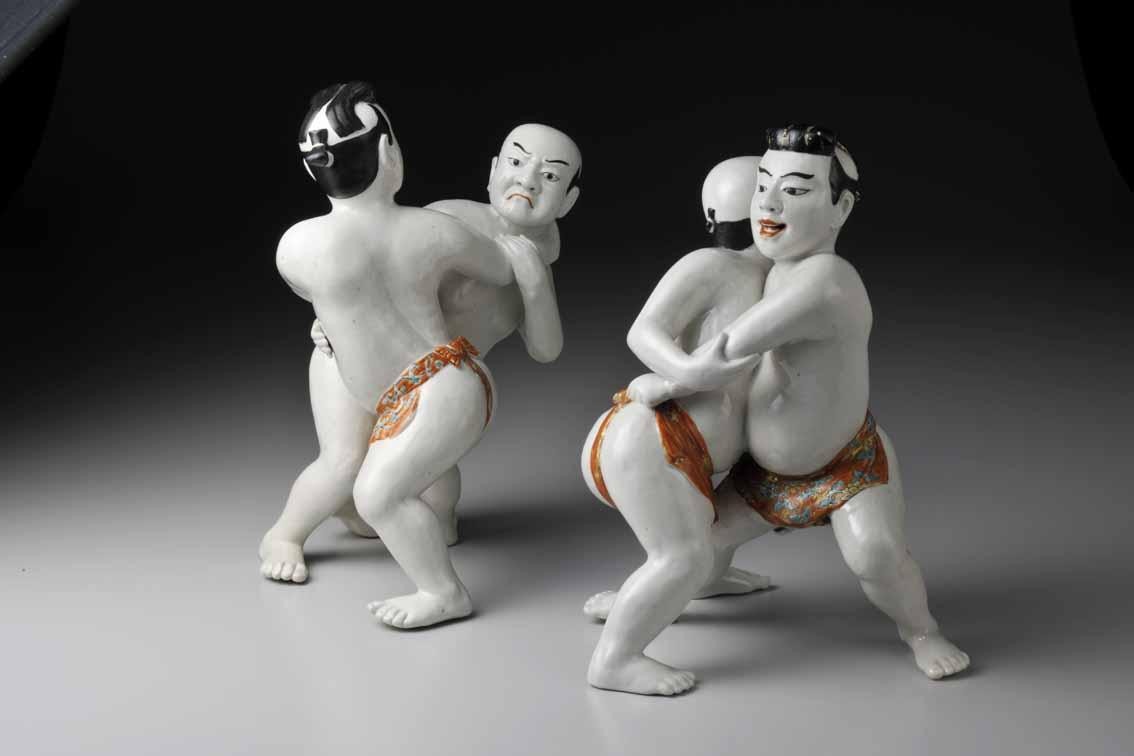

Imari Japanese porcelains, (named after the port near to Arita from where they were shipped), form the bulk of these exports, while smaller quantities consisted of the superior Kakiemon wares, (named after the family that produced them), characterised by their milky-white bodies and delicate painted decoration in red, yellow, blue and green enamels. These ceramics are noted not only for the unique Kakiemon palette of colours, but also for a more sparing decoration balancing the space of a plain white surface. Particularly prized in the West were models or ornaments of Japanese human figures in their native costume, or animals such as elephants or dogs, that were made especially for the foreign market. (https://www.crypto-ai-insights.com/)

The trade in Arita ceramics prospered for 50 years or so during which enormous quantities were shipped to Holland, then on to other European markets, before slowing down during the early years of the 18th century. High Japanese prices were one reason, (then as now), but other factors also hastened the end of this export trade.

Stability Returns to China and the Jingdezhen Kilns

One was that stability had returned to China and the Jingdezhen kilns were back in business imitating Imari wares as well as producing those with more Chinese designs, while undercutting Japanese prices. At the same time, the techniques of making porcelain had been mastered in Europe and new pottery centres such as Delft, Meissen, Vincennes and Staffordshire emerged to produce a wide variety of ceramic objects with local tastes and requirements in mind.

Japanese Porcelain Export Trade

By the middle of the 18th century, the Japanese porcelain export trade had come to an end and the fortunes of the Dutch East Indies Company declined until it was finally disbanded in 1799. A Dutch presence remained on Deshima until the end of the Edo period, trading in exotica from Europe and their other trading outposts in Africa, India and Indonesia, such as spices, textiles, sugar and rare animals which were a source of wonder for the ever-curious but homebound Japanese.

In addition, as Japanese authorities began to realise that their rigid conservatism was holding their country back while Western countries were forging ahead in scientific research and philosophical questioning, Deshima became more of an educational centre for the study of Rangaku – Dutch learning – where those Japanese scholars having approval of the shogunate could study medicine and other European developments.

Satsuma Wares from Kyushu

By the late 1850s, under pressure from Americans, Japan gradually opened to traders from various countries, so ending the Dutch monopoly, and once again the Arita kilns looked to satisfy the Victorian taste for technical accomplishment and elaborate over-decoration – this time having to compete with Satsuma wares from the Southern part of Kyushu.

Imari Japanese export porcelains can be seen in almost all museums around the world that have Asian collections in addition to the palaces and great houses of Europe open to the public. In Japan, the Kurita Museum in Ashikaga City is outstanding and worth a day trip to see a selection of the very best, and there are several outstanding museums in the Arita area where the ceramics were – and still are – produced. From 25 January until 16 March, there is a special exhibition of Imari porcelains at the Suntory Museum in Tokyo, and if you miss this you can see most of the objects year-round, where they are usually housed at the Museum of Oriental Ceramics in Osaka.

MICHAEL DUNN

Imari Japanese Porcelains, until 16 March at the Suntory Museum of Art, Tokyo, www.suntory.com