FASHION IS A form of language. What we wear broadcasts critical information about us, significant power-packed symbols. They serve as a visible sign of profession, ethnicity and status. An exhibition at Stanford University spotlights the visual symbols and meaning of clothing and objects of personal adornment in various cultures of East Asia, particularly Chinese and Japanese. This exhibition explores the art of Asian costume.

Garments and jewellery were an important indication of social rank in China. A strict code of rules regulated which colours were worn, and what motifs were used, whatever the current style. No design was merely decorative, it always had symbolic significance, and the Board of Rites laid down designs for robes each year.

History of Asian Textiles

By looking into the history of textiles like silk and ikat, the manufacturing processes of indigo-dyed fabric and batik, and other materials such as jade and bark cloth, a fascinating scenario of specific symbols and meaning emerges. The motifs, the colours, the names such as ‘lotus shoes’, which were a symbol of ethnic pride among the Han people during the Qing dynasty, even the very objects themselves like a 19th-century Qing ‘lady’s riding skirt’, speak volumes about the society which had broken and bound the feet of upper-class Chinese girls since the beginning of the Song dynasty (960-1279).

This rendered them unable to work or walk any distance without help, but nevertheless, with feet only four inches long in their ‘lotus shoes’, (the lotus symbolising purity and perfection), they rode out to hunt in embroidered silk riding skirts.

The Importance of Silk in Asian Costume

Many of the garments in this exhibition of Asian Costume are made of silk. It was ‘discovered’ in China around 2640 BC, and sericulture became its most valuable product, dominating its trade for millennia. In early history it was used as currency, and numerous works of art illustrate the vital role silk played in the Chinese economy, religious and cultural life.

One woodblock print shows a decorated altar with hanks of silk hanging above it and worshippers gathered in a shrine to the goddess of silk in Peking. Another print shows workers from a silk farm near Canton dipping a mulberry branch (on whose leaves silk worms feed) into a basin of water that stands on an altar for the silk goddess and sprinkling themselves in a rite of purification before work.

An annual sacrifice and ritual reeling of silk cocoons was an official ceremony presided over by successive empresses. No other industry was backed by the state in this significant way. Almost half of the participants were women, and interestingly, it was the only public function for which women were made Imperial Officers.

Another intriguing aspect of this Asian Costume exhibition is the long, long history of exchange and interaction between cultures of the region, creating similarities in style, materials and processes. Constant and inspirational cross-pollination of ideas and technologies occurred throughout East Asia over the centuries, creating a creative inter-connectedness across a highly diverse region.

Whether through trade, conflict or marriage, parallels in forms and techniques bounce between for example China and Korea. The insignia of a Manchurian crane on a formal silk robe identifies its wearer as a First Rank Chinese civil official. A crane also appears on the ceremonial apron of a Korean minister. In the early Qing-dynasty (1644-1911) birds were considered as symbols of literary elegance.

In Japan, from the Meiji period (1868-1912), is an unusual ‘Japanese winter kimono’ of silk satin was silk-embroidered with a group of active birds. Some are flying; others perch on swings that hang from a bamboo curtain glistening with metallic thread. The embroidered pine branches are aesthetically associated with the winter season.

The Use of Indigo in Asian Costume

The use of indigo forges another trans-continental link. An indigo-dyed Miao ceremonial jacket was made in Guizhou using a process similar to that of an Indonesian sarong. The Miao are China’s fourth-largest minority group, living in a territory that spans the country’s southwest regions. They also live in Thailand, Laos, Vietnam and Myanmar, though not in Indonesia. This richly embellished jacket made of silk, silk thread, and cotton dyed with indigo features batik patterns created by dyeing with locally grown indigo. Solid indigo has been hammered into the body of the jacket and burnished to mimic the appearance of silk. An unmarried Miao woman would have worn it during celebrations and festivals.

Indian indigo was shipped to China via the Indonesian archipelago from around 1200 onwards, though Indonesians make dye from a native indigo plant, Indigofera sumatrana. Along with spices and fragrant woods, indigo has long been an important export item from insular Southeast Asia. During the Edo and Heigi periods of Japanese history, indigo-dyed fabric was also de rigeur.

Later on, a 19th-century attushi robe in the exhibition was made by the Ainu, an indigenous population that occupy Hokkaido Island in Japan’s northernmost prefecture. Traditional Ainu clothes were made using cotton and a fibre harvested from the bark of local elm trees. Indigo-dyed cotton obtained via trade was used to create striking ornamental designs that varied regionally, with specific motifs transmitted from mother to daughter. The designs were also placed to serve a practical function, as they were believed to protect vulnerable areas of the body. These attushi would have been worn on a daily basis, accompanied by jewellery and accessories for special occasions.

Dress Showing Rank in China

Specific clothes were immediately recognisable as signals of rank in China of the past. An imposing portrait depicts a Qing-dynasty Manchu court official wearing robes befitting his status. As mentioned earlier, the crane embroidered on his crest badge indicates that he is a civil official of the first rank, while his fur-lined surcoat suggests great personal wealth. Another 19th-century formal robe, this time for a military officer of the fifth rank, is a type of garment called pu fu, literally a ‘coat with a patch’, and would have been worn as a formal outer garment.

The robes of such official Qing-dynasty officials were decorated front and back with square badges displaying the bird or beast appropriate to the wearer’s status. Animals were used to denote military ranks, big cats symbolising power and ferocity in battle. The leopard on this surcoat in the exhibition marks its wearer as a military officer. A Qing-dynasty robe embroidered with vivid purple ‘long life’ characters, signifies that it would have been made for an older woman. It would probably have been commissioned for a birthday celebration, to be presented to a mother by her children. It would then have been worn on subsequent auspicious occasions to bestow longevity on the wearer.

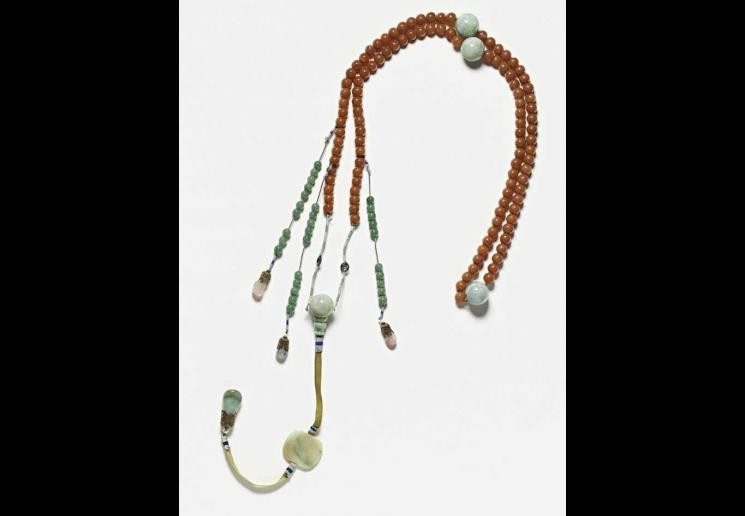

Strict regulations existed governing not only the colours and materials of jewellery, but also which official ranks were permitted to wear them. There is an exquisite court bead necklace in the show of rose quartz, carnelian, tourmaline and Burmese jade. Such necklaces were only permitted to be worn by Qing-dynasty courtiers of the Fifth Rank and their wives. The design of this particular necklace is based on Tibetan rosary beads, again demonstrating the interaction of East Asian cultures.

These beads, which were used in prayer, became fashionable at the Qing court in the late 17th century. Each necklace contains exactly 108 ‘counting beads’, with four larger ‘Buddha’s Head’ beads spaced at equal intervals. Men wore three of these three-beaded ‘counting strings’ over their left shoulders, while women wore a pair over their right. The long central pendant would have been worn down the wearer’s back as a weighted counter-balance.

Tibetan-Influenced Clothes

Another Tibetan influenced piece in this exhibition of Asian Costume is the 19th-century ‘panels from a lamaist crown’, is made of silk mounted on cardboard with silk and metal-wrapped thread embroidery. A lama, a venerated spiritual master and advanced practitioner of Tibetan Buddhism during ritual initiation ceremonies, would have worn this five-leafed crown.

Each panel depicts one of the Five Great Buddhas – Amitabha, Amoghasiddhi, Akshobhya, Ratnasambhava and Vairochana, who collectively symbolise the various aspects of enlightened consciousness. The crown is worn as a symbolic seal, indicating the individual’s shedding of the five bodily systems (material, sensational, conceptual, emotional and cognitive); and the five poisons (mirroring, equalising, individuating, accomplishing and perfecting).

Historic Asian Costume

It becomes increasingly clear that far from an individual style of dressing in historic East Asia, visual symbols and their meaning, even the shape of the garment, gave the wearer a sense of identity, of fitting in, no doubt of pride too, as it broadcasts specific status. A Chinese watercolour of a member of the Court of the Imperial Guard of 1850 shows him in an official robe, the tiger on his rank badge indicating that he is a military officer of the fourth rank. In addition, he carries a ceremonial sword.

Such watercolour drawings (often gouache) of Chinese people wearing traditional clothing and engaging in everyday activities were popular souvenirs for foreign travellers to the Canton region throughout the 17th and 18th centuries. Clearly intended for export, this one is meticulously rendered using Western techniques of shading and perspective, though the officer is placed against a plain background, in harmony with Chinese aesthetic tradition.

Dragons Were and Important Symbol in Asian Costume

Dragons were a symbol of the Chinese imperial court and emperor and were frequently featured in the design of official garments. A richly decorated Qing-dynasty man’s dragon robe (circa 1821-50) is covered with an elaborate design of clouds and dragons, woven directly into the fabric. The process of weaving a multicoloured tapestry for a robe like this one was both technically demanding and time consuming, as it required the weaver to use a separate spindle for each colour.

The narrow sleeves of the robe and their hoof-shaped openings mark it as distinctly Manchu in style. The Manchu people, originally from China’s northeast region, conquered the country and founded the Qing dynasty in the mid-17th century. Because Manchu culture placed great emphasis on horsemanship and archery, Qing court robes acknowledged this heritage. Tapered sleeves would have allowed archers great range of movement and kept the arms warm during riding, while the cuffs protected the wearer’s hands during battle.

Although again, one might not suppose that Qing dress expressed individual flair, nevertheless the owner of a ‘domestic hood’ must have felt that he or she was dressed for success. It is covered with symbols intended to bring its wearer good fortune, including five-clawed dragons, traditionally a symbol of court and emperor. But a relaxation of the regulations governing rank iconography at the end of the 19th century allowed commoners to wear embroidered dragons on formal garments.

More Chinese Symbols

Icons come thick and fast on garments in this exhibition of Asian costume. Clouds roll like waves and camouflaged among them are bats, inferring happiness, as well as numerous Buddhist symbols. These include an urn, which holds the water of life; a conch, in which the voice of Buddha can be heard; two fish, representing conjugal happiness; a canopy – the symbol of a monarch; a lotus, which as we have seen was the name given to the shoes worn by women with bound feet, and which denoted purity and perfection; and lastly an endless knot, representing longevity and the admonitions of Buddha.

Chinese Snuffbottles

A couple of Qing-dynasty bottles, one of which is of jade and coral, the other of jade alone, were designed to contain snuff, and are small enough to be held in the hand. Snuff was introduced to China by Jesuit missionaries in the late 17th century, and quickly became popular as a symbol of wealth, status and sophistication.

To the Chinese, jade was considered more precious than gold or gems. It was worn by emperors and nobles as a symbol of their authority, and was associated with death as well as life. The word yu (jade) more than hints at the symbolism and importance in Chinese culture.

That word, yu, is not only synonymous with the material itself, but was used metaphorically for ‘beauty’, ‘purity’ and ‘nobility’. So deeply embedded is it in Chinese consciousness, that the abstract qualities and physical characteristics, such as the internal radiance, extreme durability, even flaws, suggest permanence amidst the fluctuations of earthly life.

Archaeological Finds in China

Archaeological finds in several areas of China reveal that from 5000 BC jade has been worked into ritual objects, ceremonial weapons, as well as having personal and domestic functions. As jade was desirable in life, it came to be regarded as indispensable in death, protecting the body against decay. The orifices of the deceased were closed with plugs of jade to prevent the entry of evil spirits.

We learn from the earliest Chinese written records that replicas of bronze weapons were placed in tombs, along with animal shaped amulets, birds, demon masks with grotesque faces – all of jade. Although the use of jade in burial ritual began to decline during the late Han dynasty (200 BC-AD 8) and the magical properties associated with it lessened, nevertheless it continued to be used in Buddhist ceremonies. Historically it was sewn into voluminous sleeves, or attached to a belt.

Symbols Used by Nobel Families in Japan

Like the Chinese, Japanese society was highly stratified. An 18th-century, gilded-wood piece in the show, titled ‘family crests fastened to poles’, illustrates how during the Edo period noble families could be identified by hereditary crests (mon) worn on clothing or incorporated into armour and accessories. These crests, mounted on poles and designed to be visible from all directions, would have been carried during official processions and parades to indicate family lineage.

A fearsome collection of Japanese warriors’ helmets and face guards would have been worn by samurai and their retainers of the Edo period (1615-1868). Helmets known as kabuto were often highly decorative, designed to showcase the wearer’s wealth and taste, but more importantly – to intimidate enemies. Helmets and face guards were embellished with fierce grimaces, bristling facial hair and large brass teeth.

Wooldblock Prints Explore Kimono Styles

A selection of 19th-century woodblock prints showcases different forms of kimono, one of which, dated 1890, is rather endearingly titled ‘planning an overseas trip’. Another of the prints is titled with some flair ‘courtesan and her kamuro both completely in bloom in the gay quarter’. The word kimono was first adapted in Japan in the mid-19th century and means ‘the thing worn’.

As Anna Jackson, keeper of the Asian department at the V & A in London comments: ‘Kimonos are not purely decorative: indications of gender, age, status, wealth and culture are expressed through colour and pattern… (They) are designed to be interpreted, In early Japanese eras when women were often closeted, a glimpse of sleeve hanging out of a carriage would have revealed all sorts of things about the wearer. Certain opulent styles and colours were only worn at court, by samurai women (belonging to the highest-rank ruling military class), but in the Edo period, as the merchant classes grew richer and were able to afford similar styles to those of the elite, social difference marked through kimono fashion became blurred.

Sumptuary laws ere enforced to maintain the status quo, but people found ways of sidestepping them by concealing magnificent linings and undergarments beneath a plain cotton kimono, or fastening it with an ornate obi (sash)’.

So watch what you wear – it may say more about you than meets the eye.

BY JULIET HIGHET

Until 11 November, Showing Off: Identity & Display in Asian Costume, at the Iris & B Gerald Cantor Center, Stanford University, California, museum.stanford.edu