THE KOTOHIRA SHRINE – popularly known as Konpira-San – is well-known as one of the main religious centres on the island of Shikoku. Until three bridges were built during recent decades to connect the mainland and ruin the previously magical scenery, the island was remote and mysterious, having a Shangri-la image where time seemed to move at a different pace.

Throughout history Shikoku has been the destination of generations of pilgrims. Many have followed the steps of the priest Kobo Daishi (aka Kukai, 774-835) to pray at 88 Buddhist temples on a circular route around the island, while others have toured shrines – especially those housing syncretic deities, (Buddhist and Shinto), such as Kotohira.

The Main Dieity – Omononushi-no-Mikoto

The Kotohira shrine has ancient origins, and was much revered by boatmen navigating the Inland Sea. Its main deity, known as Omononushi-no-Mikoto, has been invoked through the ages to protect sailors, while the Kotohira Mountain can be seen from afar and served as a reliable bearing in often-treacherous waters. The shrine grew in importance during the warring Muromachi period, and its fortunes improved even more during the peaceful Edo period when it enjoyed patronage of both the Imperial and Shogunal courts. Today Kotohira is famous for the 1368-step climb up to the Inner Shrine, and – for the survivors – the splendid view of the Sanuki Plain and the conical, Fuji-like Mt. Iino. Palanquins were traditionally available for the lazy, and now that there is a paved road, the infirm can get to the top by taxi.

Frequent Visitors to Kotohira Shrine

Feudal lords and other high-ranking officials were frequent visitors to Kotohira shrine and suitable accommodations were built within the shrine’s vast compound to house them. Leading Kyoto artists were commissioned to decorate these guest quarters in an appropriately grand manner and a selection of these masterpieces forms the main part of this current exhibition. The shrine owns some 6,000 cultural properties, few of which to my knowledge have been seen by the public. Those on display comprise a treasure-trove of Edo painting and it is tempting to imagine what other delights are still hidden away.

Sliding Doors in the Chief Priest’s Quarters

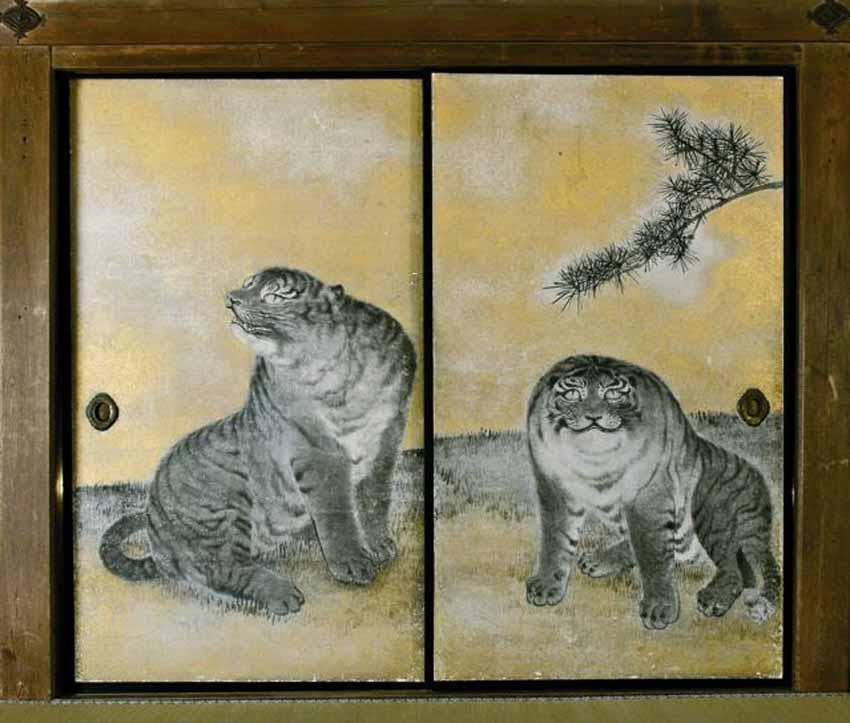

The exhibition organisers have succeeded in installing the paintings to best replicate their spacial arrangement as sliding doors and wall murals in the Chief Priest’s quarters of the Kotohira shrine, and the rooms of the Kotohira guest house. The first four rooms are decorated with paintings of – in order – cranes, tigers, Chinese sages, and landscapes, by the naturalist painter, Maruyama Okyo (1733-1795). It was certainly worth installing them this way as the visitor can now sense what it is like to be surrounded by the paintings in each room – a feeling that would be lost if they were merely lined up on a museum wall.

It is unfortunate that the Okyo paintings were ‘improved’ by some 19th-century barbarian with a splatter of gold-leaf flakes, but this was the fate suffered by many screens and sliding doors at the time and can only be looked on as part of their history. Luckily the original brush-work is more-or-less intact and the majestic scale of the paintings undiminished.

Okyo’s Tigers

Okyo’s tigers display his mastery at depicting the soft fur of the animals, but any temptation to cuddle them is dispelled by the menace suggested in their slit-pupilled eyes. One, asleep, has spots instead of stripes, but this is no leopard; at the time these were thought to be the females of the species, and a similar group can be seen on the sliding door paintings in Nanzenji Temple in Kyoto.

The landscape room is decorated with pines and pavilions in idealised scenery similar to that seen on some of Okyo’s screen paintings, and with that amazing composition – cliffs and trees going off-frame – that give the impression of looking through huge windows. It is surprising how large paintings seem perfectly in scale in small rooms, and – carrying the window analogy further – actually make the space seem much larger.

Some sort of yin/yang balance is often seen in Japanese painting and in this room, the comparatively soft landscapes on the sliding doors are balanced by a powerful wall mural of a great waterfall with rocks and old pine trees. Even if there were nothing else on show it would be worth visiting the exhibition just to see this refreshing, cooling masterpiece during the stifling days of summer.

Ito Jakuchu

The work of Ito Jakuchu (1716-1800) has been much reappraised recently thanks to the Joe Price Collection show at the Tokyo National Museum last year, and this year’s Jakuchu show at the Shokokuji Temple in Kyoto. From the rooms of the Chief Priest at Kotohira we see paintings of different wild flowers – a most extravagant wallpaper – different from anything seen elsewhere by this artist, and proof that Jakuchu was a artistically beyond any classification.

More naturalistic, waterside scenes of willow trees and herons, followed by irises and small birds, all on a gold-leaf background by Kishi Gantai (1785-1865) are on display from the quarters of the Chief Priest. Again there is this wonderful Japanese sense of composition, revealing just the centre part of a tree-trunk, or the tips of hanging branches, and giving the impression of looking out of picture windows. One can only envy the Chief Priest’s life-style on seeing other wall paintings by Gantai – there above the shoji screens and just below the ceiling – flocks of brilliant-coloured butterflies on shimmering gold.

Murata Tanryo

A contrast from all the gold – and a more modern style of painting – appears in receptions rooms decorated by Murata Tanryo (1872-1940). One of the rooms is lined with sliding doors painted with a scene of mounted hunters pursuing deer, on a plain, natural paper background. A neighbouring room with a huge wall-mural shows the crest of Mt.Fuji, while the slopes and foot-hills are painted in ink on the adjacent,sliding doors. It is certainly an unusual idea to put the subject of a painting in one room and its background in another. (https://drraisdentalavenue.com/)

Most of the displays in this exhibition reveal the paintings unhindered by glass or other protective covering – which is how they should be seen. Unfortunately, some of the Okyo paintings are behind a transparent protective barrier, under the glare of spotlights, so that the first thing one notices is one’s own reflection.

The Catalogue for the Exhibition

Fortunately the photographs in the accompanying catalogue were taken in situ in the Kotohira Shrine compound. Helpful diagrams show just how the paintings are located in each room of the shrine buildings, and will provide an invaluable reference for any future visit to Kotohira after the art works have been reinstalled following their tour. The essays are in Japanese, together with English translations in the kind of unreadable gobbledegook that we have come to expect from institutions of higher education in this country. While endlessly entertaining when seen on t-shirts and shopping bags, this sloppy language is simply not up to standard for a catalogue such as this.

No western institution would dream of publishing anything in Japanese without employing a competent, native Japanese proof-reader, so one wonders why, considering the cost of making this beautifully printed book, the eminent bodies behind this project could not see their way to hire an educated, native English-speaker to clean up the text? Okyo, Jakuchu, and Gantai deserve better than this.

BY MICHAEL DUNN

The exhibition was originally seen at the The University Art Museum, Tokyo National University of Fine Arts and Music last year and has now moved back to the Kotohira Shrine before travelling later this year to the Mie Prefectural Museum of Art, and – for the first time out of Japan – at the Musée Guimet in Paris.