This exhibition, Epic Iran, which should have opened in February, is now scheduled to open in mid-May. It is on a grand scale – aiming to explore 5,000 years of Iranian art, design and culture, bringing together over 300 objects from ancient, Islamic, and contemporary Iran. It is also the UK’s first major exhibition of Iranian art in 90 years, after The International Exhibition of Persian Art, held at Burlington House in London in 1931 and will present an overarching narrative of Iran from 3000 BC to the present day.

Iran was home to one of the great historic civilisations, yet its monumental artistic achievements remain unknown to many. Epic Iran takes a visual journey through this civilisation and the country’s journey into the 21st century, from the earliest known writing – signalling the beginning of history in Iran – through to the 1979 Revolution and beyond. Ranging from sculpture, ceramics and carpets, to textiles, photography and film, works will reflect the country’s vibrant historic culture, architectural splendours, the abundance of myth, poetry and tradition that have been central to Iranian identity for millennia, and the evolving, self-renewing culture evident today. From the highly important Cyrus Cylinder and illuminated manuscripts of the Shahnameh, to 10-metre-long paintings of Isfahan tile work to Shirin Neshat’s powerful two-screen video installation Turbulent, showing with Shirin Aliabadi’s striking photograph of a young woman blowing bubblegum, the exhibition offers a new and fresh perspective on a country that is so often seen through a very different lens in the news.

Persian Art at the V&A

The Victoria & Albert Museum has collected the art of Iran since the museum’s founding over 150 years ago and has one of the world’s leading collections from the medieval and modern periods. Drawing on well-known highlights from the collection, as well as works that have not been on display in living memory, the exhibition has also organised important international loans and works from significant private collections, including The Sarikhani Collection based in the UK.

Epic Iran is divided into 10 sections set within an immersive design that transports visitors to a city complete with gatehouse, gardens, palace and library. Designed by Gort Scott Architects, each section will have a different atmosphere to reflect the objects displayed, as well relating them to their time and place in history. The first section introduces the ‘Land of Iran’ with striking imagery of the country’s dramatic and varied landscapes. Iran is home to mountain ranges, searing deserts and salt pans, as well as lush forests and varied coastlines – all of which have shaped the country’s social, economic and political history – and it is from this landscape that the artistic cultures explored in this exhibition emerged over the past 5,000 years.

Earliest History of Iran

Beginning at the dawn of history in 3200 BC and marked by the earliest known writing, the section ‘Emerging Iran’ shows that even before the rise of the Persian Empire, Iran’s rich civilisation rivalled those of Egypt and Mesopotamia. Animals and nature are a recurring motif – reflecting their importance in society at the time – with ibexes, gazelles, lions, and birds decorating pottery, cups, axe heads and gold beakers. The section also features figurines and items from everyday life including earrings, belt fragments, and a board game. The Elamites dominated southwest Iran during this time, but from 1500 BC Iranian-speaking people began arriving from Central Asia.

The Persian Empire and Epic Iran

The third part of Epic Iran, ‘The Persian Empire’ spans the Achaemenid period, starting in 550 BC when Cyrus the Great was crowned king of the Medes and Persians, uniting Iran politically for the first time. With its capital Persepolis, the empire became the most extensive of the pre-Roman world, with a rich artistic culture. Archaeological finds reveal insights into kingship and royal power, trade and governance of society, which will be explored in a dramatic section by using stone reliefs from Persepolis with large-scale casts with what would have been the original colours projected onto them. Also on display will be such metalwork as jewellery, coins, gold objects and silverware. Highlights, here, include the Cyrus Cylinder (on loan from the British Museum) and a gold armlet from the V&A’s collection in the Oxus Treasure. The section will also feature a series of eight plaster casts from the V&A, cast from frieze panels from the Palace of Darius at Susa, in Khuzistan province.

‘Last of the Ancient Empires’ comes next and covers a period of dynastic change with Alexander the Great overthrowing the Persian Empire in 331 BC. The Greeks were quickly replaced by the Parthians, who were in turn defeated by the Sasanians. 400 years of stable reign followed: Zoroastrianism became the state faith and strong art and architecture traditions developed, with the Sasanian style enduring long beyond the dynasty’s fall. The section showcases Parthian and Sasanian sculpture, stone reliefs, gold and silverware, coins, as well as Zoroastrian iconography. Zoroastrianism, or Mazdayasna, is one of the world’s oldest continuously practised religions, based on the teaching of the prophet Zoroaster and served as the state religion for ancient Iranian empires. The religion still exists today, particularly in India. Other highlights in the Ancient Empires section include royal busts, such as a 5th-century royal bust from The Sarikhani Collection, and a silver ewer from the Wyvern Collection, depicting women dancing.

The Book of Kings

The fifth section in Epic Iran, ‘The Book of Kings’, is a prelude to the sections devoted to Islamic Iran. It shows how Iran’s long history before the coming of Islam was understood in later centuries – primarily through the Shahnameh, or Book of Kings, which is considered by many as the world’s greatest epic poem, completed by the Iranian poet Firdowsi around 1010. Combining myth, legend, and history, this national poem of Greater Iran provides a widely honoured and therefore powerful version of events, defining Iran and its long history in the minds of its people. Consisting of more than 50,000 rhyming couplets and is considered the longest poem ever written by a single author. The book begins with the creation of the world, continues with an evocation of the legendary kings and then, after Iskander (Alexander the Great), with a historiography of the dynasties up to the arrival of Islam. Its popularity grew from the 14th century onwards and continues today. The exhibition features a series of elaborate illustrated manuscripts and folios depicting scenes from a Shahnameh (on loan from The Sarikhani Collection) and other folios from British Library, among others.

The Arab Conquest in Epic Iran

The section ‘Change of Faith’ explores the place of Islam in Iranian culture in the millennium and more that followed the Arab conquest of the area in the mid-7th century. The 1500s saw the rise of Safavid Empire, a dynasty that ruled over Persia from 1501 to 1736, and the start of their rule is often considered the beginning of modern Iranian history. The Safavid dynasty had its origin in the Safavid order of Sufism, which was established in the city of Ardabil in the Azerbaijan region and introduced the Shia faith to the population. The first rule, Shah Ismai’l (1501-24), proclaimed himself a descendent of Ali via the seventh Shi’ite imam, and was duly accorded divine status by his Turkomen followers. Under Shah Abbas (1587-1629), Iran became a multicultural and modern state with the country entering a period of extraordinary growth and splendour in architecture, the arts, and literature. His new capital, Isfahan, was planned with a great avenue, a central square, gardens and pavilions, as well as a dedicated commercial sector and a state bazaar.

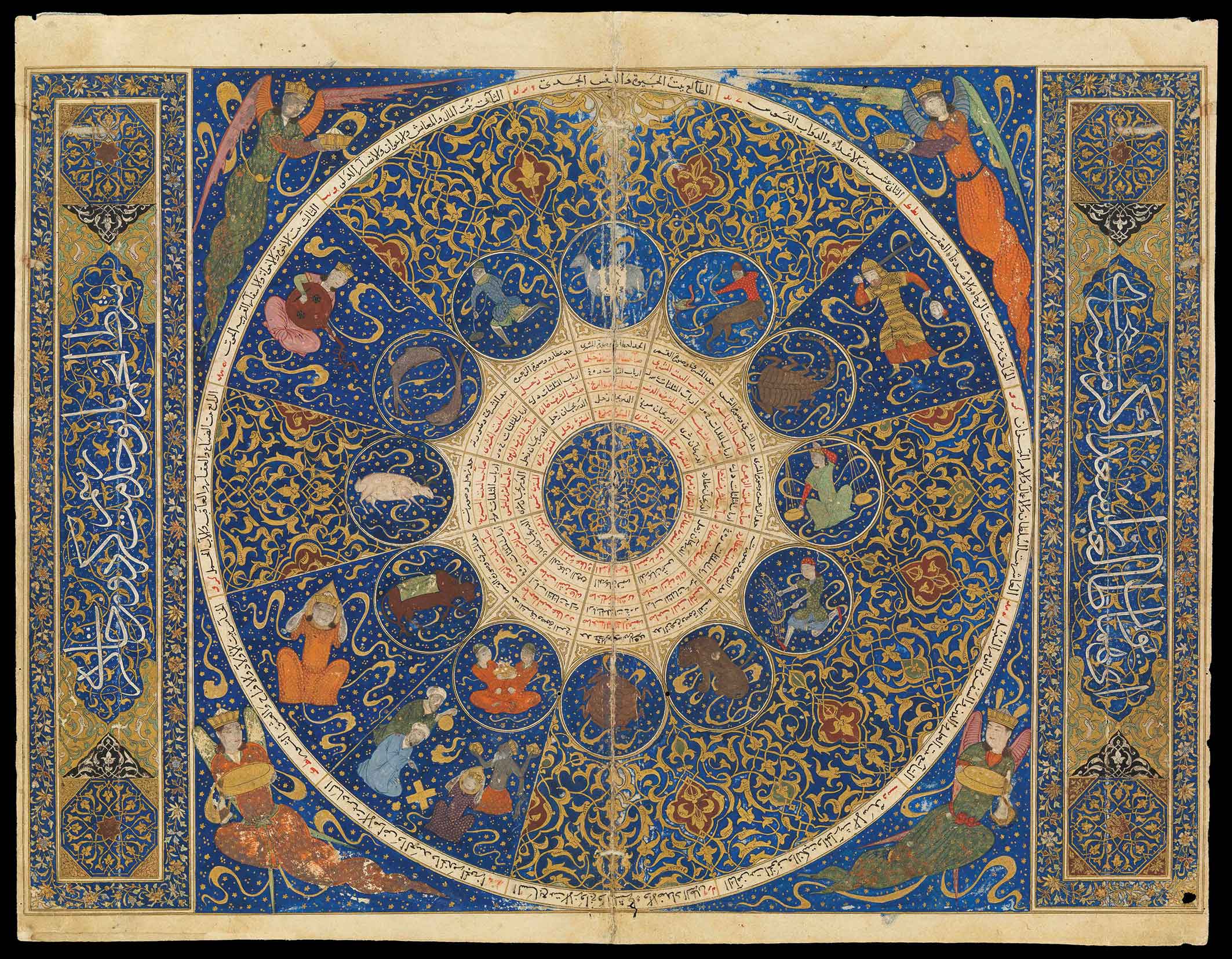

The Qur’an is also explored in this theme, in Epic Iran, with the text in Arabic that forms the basis of Islam – as well as the role of the Arabic language in Iran after the conquest. Arabic became the common language of intellectual life in the country, while the art of calligraphy in the Arabic script became highly developed and an important element in Iranian design. The section also looks at how conversion to Islam gave Iranians a new understanding of history focused on the Prophet Muhammad and his immediate successors. Disputes over the events of this period lie at the heart of the split between Sunnis and Shi’ites, and they took on great significance from the early 1500s, when the Imami form of Shi’ism became the country’s official religion. A number of exquisite Qur’ans and manuscript illuminations feature, alongside a prayer rug, battle and parade armour, a celestial globe, and the magnificent 15th-century Horoscope of Iskandar Sultan, on loan from the Wellcome Collection.

Persian Poetry in Epic Iran

Charting the rise of Persian poetry, ‘Literary Excellence’ reveals how, from the 10th century onwards, Persian written in the Arabic script emerged as a literary language in the royal courts of eastern Iran. Royal patronage meant manuscripts were incredibly refined and poetry became part of the visual arts because of the use of poetic inscriptions, which appeared on items including ceramics, metalwork, and even carpets. The V&A’s Salting Carpet includes verses by Hafiz in its border, whilst a bottle and bowl from the 12th century, decorated in lustre pigments, feature poetry in Persian. Much was also written in praise of rulers, with poetry finding its visual counterparts in art representing royal power.

Epic Iran features rich material from the 13th century onwards, the section on ‘Royal Patronage’ demonstrates how Iranian traditions of kingship were reborn after Islam, with the return of royal customs like robes of honour, the creation of lavish art and architecture, and an insight into internationalism as a two-way exchange. Recreating the splendour of Isfahan, three 10-metre-long paintings that replicate tile work patterns from the city’s domes are suspended in arcs from the ceiling to suggest a dome interior. These are displayed alongside an AV (audio/visual) projection that uses the paintings to re-construct the appearance of the full dome. Technical architectural drawings from the 19th century and a selection of tiles complementing the paintings, and the section looks at how Iran took on influences from the wider world – from China and Europe in particular – as is apparent, for example, from the development of blue-and-white ceramics. Important Iranian objects that have been in Britain for three centuries also feature, including the Buccleuch Sanguszko Carpet and two oil paintings (on loan from Her Majesty The Queen, the Royal Collection).

The Qajar Dynasty

The ‘Old and the New’ section will explore how the Qajar dynasty looked back to their predecessors to legitimise their power, whilst also seeking to modernise and scope out new relationships with Europe. The Qajars came to power following the assassination of Nadir Shah in 1747 and after a period of turmoil emerged as the ruling dynasty at the end of the 18th century as was to reform Iran into a modern state for the era.

New technologies over the centuries are also explored, including the introduction of photography in Iran in the mid-1800s. This, naturally, had a profound effect on the way Iranians represented themselves, moving away from paintings into the modern world of not only portrait photography, but landscapes and a means of recording the fast-evolving world around them. Fashion is also a subject that features in the exhibition, juxtaposing a full outfit, a short skirt likely influenced by European ballet tutus, and watercolour paintings of Iranian women made for tourists visiting the country. The final part of the section will look at how Iranian craftsmen sought new markets for their skills in the 1880s, when their new clientele included the V&A itself.

Contemporary Iranian Art in Epic Iran

Bridging the 1940s to the present day, the final section ‘Modern and Contemporary Iran’ covers a period of huge dynamic social and political change in Iran, encompassing increased international travel as well as political dissent, the Islamic Revolution, the Iran-Iraq War, and the establishment of the Islamic Republic. Works by Sirak Melkonian, Parviz Tanavoli, Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian and Bahman Mohasses will showcase the mid-century explosion of artistic modernisms, brought to a dramatic end with the 1979 Revolution and Iran-Iraq War. The cultural scene flourished again in the 1990s under the mercantilism of Rafsanjani and liberalism of Khatami, and modern technology means Iranian contemporary art exists in a world without boundaries. Today, Iran has an evolving, self-renewing culture: some works are informed by past traditions, and many are radical and experimental both in medium and expression. Gender, politics, religion and identity issues are frequently multi-layered and often approached with humour and irony, testing the boundaries of censorship and control.

The exhibition will also feature work by Iranian artists living in Iran, as well as those based overseas, with works by Farhad Moshiri, Avish Khebrezadeh, Ali Banisadr, Shadi Ghadirian, Hossein Valamanesh, Shirin Neshat, Shirin Aliabadi, Shirazeh Houshiary and Y Z Kami.

Epic Iran, scheduled to open in May at the Victoria & Albert Museum, London, vam.ac.uk. Catalogue available.