Often condemned as a mad eccentric, the monk-artist Bada Shanren also known as Zhu Da, created some of the most daring and powerful paintings in 17th-century China. Wayward compositions with many layers of meanings, they largely reflected his tortured inner emotions and particularly the trauma of his life.

Born a prince of the Ming (1368-1644) imperial house of Zhu at Nanchang, Jiangxi in 1626, he was eighteen when Manchu armies swept south and took Beijing, overthrowing the Ming to establish the Qing dynasty (1644-1911).

When Nanchang was occupied in 1645, Zhu Da, a direct Ming descendant, feared retaliation and went into hiding. He retreated to a Buddhist monastery in the mountains, and sought anonymity as a monk for more than 30 years. As the perils of conquest receded in the 1670s, Zhu Da left the priesthood and returned to secular life in Nanchang as a professional artist, calligrapher and poet.

Wild and Eccentric Behaviour

His wild and eccentric behaviour – feigned or otherwise – was attributed to a nervous breakdown, following which he treated painting to his idiosyncrasies, using an individualistic and outlandish style that was uniquely his. The name Zhu Da never appeared as a signature or seal in his work. In 1684, he took the name Bada Shanren, which remained with him for the rest of his life.

If the composition, symbolism and meaning of his work had left Bada’s contemporaries puzzled and perplexed, their same enigmatic qualities continue to elude us 300 years later. The contemplating of Bada’s art however has its limits; although he painted for almost half a century, less than 200 of his known dated works are extant.

Freer Gallery of Bada Shanren’s Paintings

‘The Freer Gallery of Art owns 72 individual works, the largest, most diverse and arguably the most significant collection of Bada Shanren’s art outside China,’ says Stephen Allee, Associate Curator for Chinese painting and calligraphy at the Smithsonian’s Freer and Sackler Galleries. ‘

The bulk of this collection was assembled privately over many years by the scholar, Wang Fangyu (1913-1997) who identified a group of works as its core, to be kept intact and given upon his demise to a major museum. In 1998, Wang’s estate presented them to the Freer, which also purchased a small group of calligraphy from his collection.’

This exceptional collection has enabled the Freer to mount Enigmas: The Art of Bada Shanren (1626-1705) with a broad selection of 51 works that rank among the artist’s finest; 44 by Bada and seven calligraphy leaves by an unidentified contemporary – possibly the monk Fayi, who occasionally collaborated with him. They offer rare insights, tracing the evolution of Bada’s work from his monkhood in the 1660s to his peak professional years in the 1680s and 1690s, and to last years as a hermit in the early 1700s.

Enigmatic Quality of the Work

‘The enigmatic quality of Bada Shanren’s work brings one back to his art again and again,’ says Dr Allee. ‘Trying to fathom some ambiguous aspect of a painting or calligraphy, one is convinced there is a key to unlocking the mysteries, cracking the code and that maybe this will be the time one stumbles across it.

Of course, one never really finds the answer – Bada Shanren is too self-contained an artist for that – but the quest is always rewarding, as each careful viewing invariably yields new pleasures and discoveries.’

Bada’s talent had been recognised even when he was a monk. He was known as Xuege, or Xuege Shangren, ‘Abbot Xuege’. However, very few paintings have survived from this period of his life, and no extant works date before 1659. Among the earliest surviving are two important album leaves, Lotus (circa 1665), bearing the signatures and seals of his Buddhist names, Chuanqi, which he used for 26 years, Ren’an and Fajue.

They betray Bada Shanren’s spiritual kinship with the lotus, a Buddhist symbol of purity and rebirth that dominated his visual vocabulary from the beginning to the very end. These early ink wash experiments already possess a raw energy, attesting to Bada’s clever manipulation of ink and calligraphic skills. Using lotus stalks as a device to cut diagonally across the composition, he leaves the centre an empty void, so that the focus falls on the object at the edge of the frame.

This asymmetrical compositional style became one of his hallmarks, and was modified throughout his life. It remains open to interpretation: ‘Such random, fragmentary views may reflect Bada’s marginal status as a former prince living clandestinely under an alien regime,’ says Dr Allee.

Not Known Why He Took the Name Bada Shanren

It is not known why he took the name Bada Shanren, meaning ‘Eight Eminent Mountain Men’ in 1684. In this connection, among Bada’s surviving works, the album, Huangting neijing jing, ‘Scripture of the Inner Radiances of the Yellow Court’ is particularly significant.

It is the earliest known work bearing the Bada Shanren signature; where a colophon dated ‘first day of the seventh lunar-month in the jiazi year’, August 11, 1684, indicates that it was already in use. The 4th-century scripture is one of the most influential texts of mediaeval Chinese Daoism and has a long history in the calligraphic tradition, beginning with the famous Wang Xizhi’s (circa 303-circa 361) script.

Acknowledging the latter in his colophon, Bada typically wrote the text using his own reinterpretation of 4th century script – developed through copying writing and stone inscriptions from the ancient past.It has been speculated that Bada’s calligraphy, which he practised already as a child and continuously throughout his life, surpasses his painting.

Extensive Knowledge of Calligraphic Forms

His extensive knowledge of calligraphic forms ranged from the seal and clerical scripts, to all manner of the cursive, as well as the standard and running forms. Clearly his roots in the Yiyang branch of the Ming imperial family never left him. Having grown up surrounded by renowned calligraphers and painters, Bada emerged a remarkable scholar-poet.

Moreover he was partial to the ‘wild cursive’ script of the Tang (618-906) calligrapher and monk, Huaisu (circa 725-circa 799) and had a special affinity for Tang poetry, particularly the works of Ouyang Xun (557-641), Li Bo (701-762), and Meng Jiao (751-814) among others, which stood him in good stead. ‘Poetry describes going forth and staying put, paintings express both the empty and the full,’ he once said, quoting Sun Ti (circa 699-circa 761), another Tang literatus.

One of Bada’s most spectacular calligraphic works to survive is his rendition of the 12-line Tang Poem by Geng Wei in cursive script, (circa 1699), where his strong and forceful script, each ideogram individually realised and only occasionally linked, attests to his inimitable mature style.

Most Prolific Period was the 1680s

The 1680s were the most prolific period of Bada’s life, when he created many of his masterpieces. His need for income and recognition saw him expanding his repertoire, adding birds and fish, insects, small creatures, flowers, plants and later, rocks. Bada was particularly adept at painting several varieties of fish and birds.

They represented freedom and appeared again and again, sometimes distorted and often charged with emotion. Their glaring eyes, sinister and watchful, harboured complex messages, their symbolism known only to him.

These daring, but deceptively simple works – usually executed on small-scale album leaves – were averse to colour. They were characterised by flat angular brushwork that Bada employed to full effect, using the side hairs of the brush.

Perfecting his technique of layering ink, he gave his subjects a subtle texturing, tonal variation and visual depth. They are visible on an arresting fish image portrayed with a stark single eye: It forms part of Birds, Flowers, Insects and Fish (circa 1688-89), the first genuine Bada Shanren album that the Freer purchased in 1955, where many calligraphy leaves of original poetic couplets bear a seal impression by the monk Fayi (mid-late 17th century).

Bada went on to consign the established rules of traditional Chinese painting to oblivion. He replaced the correct pairing of creatures and plants with a scheme of exaggerated scale and scope that was his alone. Juxtaposing odd elements from his repertoire, he transported fish and rock, bird and lotus, and other creatures, to another realm.

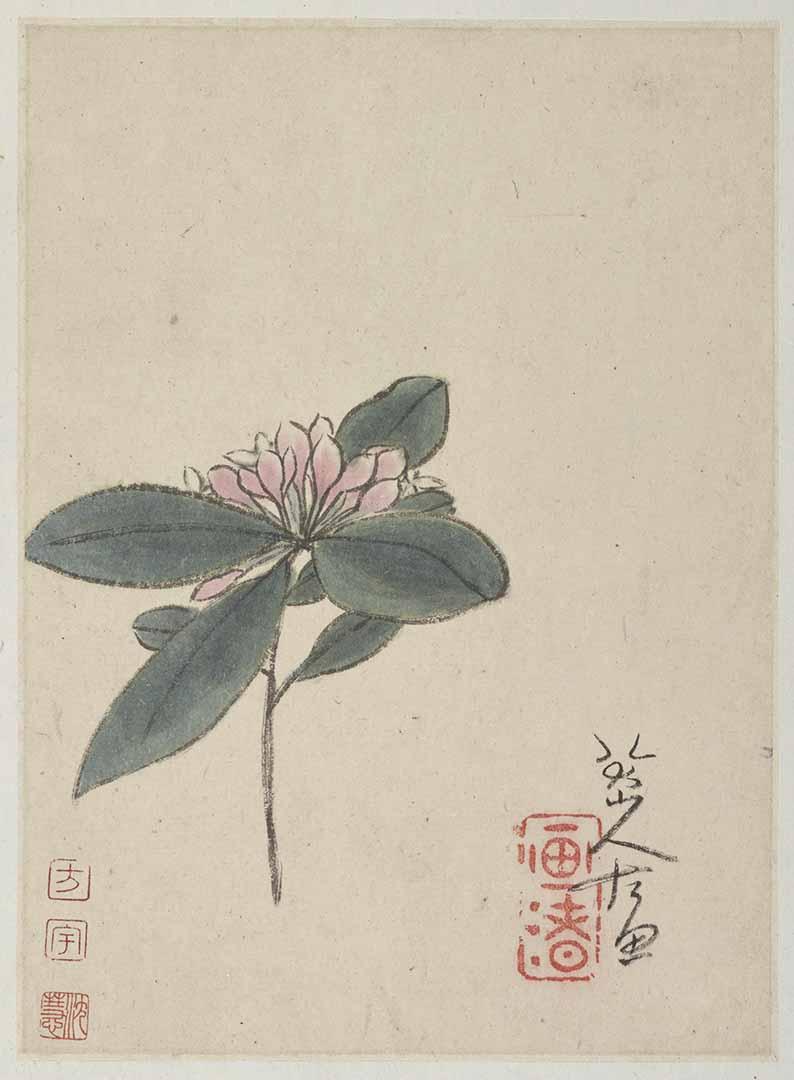

In a rare departure, Bada painted Lilac (circa 1690), a subject not usually in his repertoire, adding uncharacteristically, deep opaque colours. Its symbolism remains elusive. Bada said he was ‘imitating the painting style of Bao Shan’, a sobriquet for the painter Lu Zhi (1496-1576), but the latter’s sensitive flower studies were at odds with this work.

Bada Shanren’s Seal

Unexplained too is Bada’s seal, perhaps an ideogram for ‘mountain’, impressed on the composition. The 1690s were a period of wide-ranging artistic exploration when Bada elevated his work to near abstraction. Between 1690 and 1693, his brush burst with renewed energy, as its nuanced use of ink achieved a wider range of tonal effects, from wet and light to heavy and dark.

‘In writing too, (one) must be free from fear in order to be competent,’ he wrote, ‘the same holds for painting, therefore when it comes to painting, I respectfully call it sheshi, ‘working things through’.’ This exercise seemed confined to lone subjects. They were almost sketches such as Falling Flower (circa 1692), a single blossom on an album leaf, dominated by two bold ideograms for sheshi, written with complete assurance, as its main design component.

Transition from Small-scale Album Leaves to Hanging Scrolls

Meanwhile, Bada made the transition from small-scale album leaves to the mighty hanging scroll. The larger format brought the flourishes of his brushwork and his acute powers of observation to the fore. In the magnificent Lotus and Ducks (circa 1696), he resurrects the lotus theme from his Buddhist consciousness, complementing it by adding ducks, one of his favourite creatures.

Exceptionally tall lotus stalks swaying on the right, surround a central void bordered by a threatening rock face on the left. The lotus and the void have Chan philosophical connotations and refer to Bada’s erstwhile experience as a monk. But he has a reason for juxtaposing ducks. They are animated and have human emotions:

The one perched high on the cliff gazes down at the other resting on a rock below, the whites of their eyes strongly emphasised to signify anger. This trait, says a poem inscribed by Wu Changshuo (1844-1927) in 1926, suggests the destruction of the Ming as the source of Bada’s anger.

Towards the End of Bada Shanren’s Life

Towards the end of his life Bada resurrected the familiar imagery and symbolism of Chan Buddhism where gradual enlightenment was pursued through study and meditation. He chose wild geese, which held a special place in this sphere of things, and among his most popular themes, to convey his message.

Usually executed in pairs to suggest companionship, they also alluded to ideas of travel, separation and political exile. Two Geese (circa 1700), a combination of Bada’s lightning strokes and sharp smears, shows him at his most sublime. One goose is depicted upright and alert, the other in slumber; they allude to togetherness in a troubled world, embodied by the cliff overhang.

Started to Paint Landscapes When He Was Nearly 70

In 1693, when he was nearly seventy, Bada began to seriously paint the landscape. The subject had eluded him in 1681, when he signed off his clumsy early attempts with the name, lu, ‘donkey’. Twelve years later, he was ready to finally take it on.

He was merely following in the footsteps of past Chinese masters who embarked on the landscape, only to revitalise it, in their mature years. The great Yuan (1279-1368) master, Huang Gongwang (1269-1354) for instance, executed his masterpiece, Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains at the age of eighty, considered the pinnacle of his career.

Most of Bada’s landscapes appear contemplative. They bear little anger, suggesting that after nearly five decades as a yimin, ‘leftover Ming subject’, he was finally reconciled to his existence and at peace with himself. Moreover he brought the ideal, shuhua tongyuan, ‘calligraphy and painting have the same origins’ that he had subscribed to throughout, to fruition. By combining abstract, calligraphic brushwork and ambiguous spatial relationships in Four Landscapes from a Combined Album of Painting and Calligraphy (circa 1693-96), he achieved free self-expression.

Admiration for 10th-Century Master Dong Yuan

Still, he acknowledged his debt to past masters. The elements of rounded rock forms and low rolling hills reflect his admiration for the 10th-century master, Dong Yuan’s (d 962) gentle landscape style which conveyed qualities of pingdan tianzhen, ‘blandness and naturalness’.

Bada also paid a lasting tribute to his mentor, the late Ming master, Dong Qichang (1555-1636), his greatest artistic inspiration. Copies of Ancient Landscape Paintings (circa 1697) is an exact copy of Dong’s now-lost album and occupies a unique place in Bada’s oeuvre; he follows the former’s brushwork and compositions, faithfully copying his inscriptions and signatures, while identifying himself as the actual artist.

Bada remained committed to his painting until the end. He consistently refined his brush technique, exploring graduated ink tones, and experimented with their possibilities as he lived out his last years seeking solace with the natural order.

The exhibition shows us Bada Shanren as he really was, a genius like no other artist before him. He had a compelling and lasting influence on a generation of early 20th-century Chinese painters who recognised him as the foremost proponent of abstraction, well ahead of his time.

‘This is the Freer’s final exhibition before it closes for major renovations in 2016,’ says Dr Allee. ‘When it reopens in 2017, there will be no gallery space set aside for Chinese painting and calligraphy that will be large enough for such an exhibition. So this is the last opportunity for a while to have a large selection of Bada Shanren’s art on view at one time.’

BY YVONNE TAN

Enigmas: The Art of Bada Shanren (1626-1705) is at the Smithsonian’s Freer Gallery of Art, 1050 Independence Avenue SW, Washington DC, until 3 January 2016. www.asia.si.edu