In the summer of 1978, Nancy Berliner, currently Wu Tung Curator of Chinese Art at the Museum of Fine Arts (MFA), Boston, was visiting Taiwan and came across an unusual painting at a Taipei flea market stall. She was ‘intrigued by its very modern appearance and (since) it looked almost like the collages of Picasso and Braque’, brought it home and start the rediscover of Bapo painting.

In succeeding years, neither Chinese art specialists in the US nor their counterparts in China were able to enlighten her about the work. Her tireless efforts in its pursuit have made Dr Berliner the first scholar to have undertaken a comprehensive study of what is known as bapo painting.

Bapo or ‘Eight Brokens’

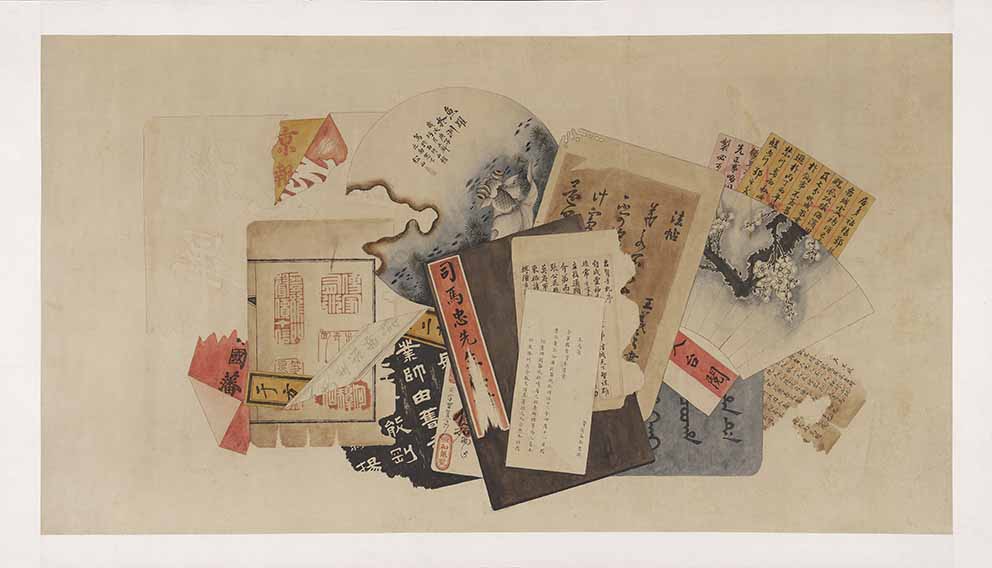

Bapo or ‘eight brokens’ was a revolutionary art form that surfaced in mid-19th century China. Radically distinct from classical Chinese painting, it employed an illusionist technique of representation by deconstructing cultural ephemera to create images on paper. Bapo was focused mainly on the written word. Its offerings included fragments of moth-eaten calligraphies, partial book pages, remnants of stone rubbings and seal inscriptions, torn letters and burned or decomposing paintings.

The genre went on to delight the urban intelligentsia with its unconventional, and occasionally whimsical qualities, which were often accompanied by hidden commentary, aphorism and pun. But it was not taken seriously. Although its output extended until the mid-20th century, the Communist takeover of China in 1949 saw it fizzling out, before slipping into obscurity.

‘There is no known originator of the term bapo,’ says Dr Berliner. ‘It was a popular term in northern China for this form of art. There were numerous other appellations that appeared in different regions of China; including jinhuidui, ‘a pile of brocade ashes’, duanjian canpian, ‘broken bamboo slats and damaged sheets’, and baisui tu, ‘a picture of 100 years’ because the Chinese word sui, ‘year’ is a homonym with the word for ‘fragment.’

Eight is A Number of Good Fortune

‘Eight is a number symbolising good fortune in China,’ she says. ‘In Buddhism, many symbols come in groups of eight, such as baku, ‘the eight precepts and the eight distresses’. Many other groups of objects in Chinese culture were thus grouped into sets of eight: Eight treasures, eight immortals, eight Daoist trigrams, among them. Babeizi for instance, means ‘eight lifetimes’.

Many ‘eights’ also occur in traditional Chinese medicine and acupuncture. In Chinese cuisine, there is babaofan, ‘eight treasured rice’. Why broken? Because the objects in these paintings are all broken or damaged. Many bapo paintings – with their deteriorating remnants of traditional culture – are also declarations of mourning for the past, but others are filled with humour and hidden messages.’

China’s 8 Brokens: Puzzles of the Treasured Past

The exhibition, China’s 8 Brokens: Puzzles of the Treasured Past at the MFA, Boston – the first on the subject – has been designed ‘to assist viewers in decoding and delighting in these puzzles’ by drawing from the largest assemblage of bapo in any public institution.

Some of these date back to the 19th century and are juxtaposed, to provide a means of comparison, alongside bapo imagery found on Chinese three-dimensional objects – including inside-painted snuff bottles and painted porcelain. Several European and American trompe-l’oeil, ‘deceive the eye’ paintings have also been gathered to illustrate how the genre resonates visually with western works of the same period.

Bapo Aesthetic

The bapo aesthetic however, grew directly out of Chinese visual traditions. The practice of pasting multiple, cherished calligraphies or paintings on a single panel such as a screen, might be traced to 8th-century Tang China. It flourished again in the 17th century, reflecting a tendency among some nouveau riche to flaunt in full measure the contents of their personal collections.

‘The decorative style of multiple paintings pasted or painted on to a single surface appeared in the hejin, ‘assembled brocade’ screens in the 17th and 18th centuries, and on porcelain decoration,’ says Dr Berliner. ‘They were a definite root of bapo paintings. On these screens were pasted complete paintings or calligraphies, rectangular or round, such as album leaves or round fan paintings. They were composed in orderly arrangements – because before the mature form of bapo developed, artists painted similar arrangements of paintings and calligraphies in orderly compositions.’

Elite Culture of the Qing Dynasty

Many elements appearing in bapo reflected the elite culture of Qing dynasty (1644-1911), or Manchu China’s growing fascination with ancient written forms. The ‘seal’ script from antiquity and the Han (206 BC- AD 220) ‘clerical’ script in particular took pride of place. Newly published works on the seal script in the 17th century had encouraged the copying of inscriptions on famous monuments such as stone stelae. These visual records led to a revival of interest in ancient forms of writing in the 18th and 19th centuries, inspiring both literatus and artist, to investigate them further.

The Eccentric Monk Artist Liuzhou

‘The rising interest among the scholarly class in jinshixue, ‘epigraphy’, the study of ancient calligraphic inscriptions on stone, and on metal, went hand in hand with the growth of collecting rubbings of these inscriptions,’ says Dr Berliner. ‘The eccentric monk artist, Liuzhou – an epigraphy connoisseur and friend of the famous epigraphist and collector, Ruan Yuan (1764-1849), produced collaged rubbings in the 1830s, which may have been the first aesthetic creations that instigated bapo paintings. There was at the same time, a corresponding growth of paintings representing bogu, ‘ancient objects’, such as historic ceramics, archaic bronzes, books and other antiquities.’

Qianlong-period Catalogue

The making of new Chinese art objects in the various ancient styles had been directly influenced by an imperially sponsored philological, ‘science of language’ project, a century before. The publication in 1749 during the Qianlong period (1736-1795) of a catalogue of the archaic imperial bronze collection had provided an important template for their manufacture. It included the inscriptions cast on these objects, and became an invaluable resource for scholars studying early script forms. The substantial increase in rubbings of early bronze inscriptions went on to make the ancient seal and clerical scripts become widely known.

A New Style of Work Using Decomposing Paper

Around the 1850s, a number of artists from across China – some of whom were classically trained – began to embark on a surprising new genre. They created illusionist compositions haphazardly pasted with decomposing papers and artefacts, contributing to a trend that carried into the 20th century. Traditional Chinese society held scholars and their lifestyle in high esteem, and bapo soon became a repository for the paper accoutrements of literati life: Stone rubbings of ancient scripts, classical writings and treasured artefacts from antiquity. Some of its contents posed a challenge: The ability to correctly identify a famous painting or poem being depicted, was a test of the viewer’s cultural sophistication.

The Artist Liu Tianjin

One prominent example is Lotus Summer of the Xinghai Year (1911) by Liu Linheng (1870-1949) from Tianjin. It is in the scroll painting format, and carries, apart from painted, printed and inscribed papers, a conspicuous fan painting. The folding fan was not a Chinese invention but arrived in Ming China (1368-1644) from Japan. Its surfaces, both front and back, were used thereafter to depict landscape subjects as well as calligraphy and poetry.

Liu’s fan bears an inscription ‘signed’ by his teacher, Liu Yecun, recognising its monochrome landscape as an 18th-century imitation of A Delightful Garden (circa 1698) by Wang Hui (1632-1717), a professional artist in the court of the Kangxi emperor (r 1662-1722). In China, the copying of earlier masterpieces was regularly practised as a teaching aid, but the fan in this instance was ‘an imitation of an imitation of an imitation’.

Liu’s Bapo

Liu’s bapo contains other literati accoutrements besides. His brushwork portrayed both an archaic bronze vessel as a three-dimensional rubbing, and a fragment of an actual rubbing on a stone stele erected in 137 to record General Pei Cen’s defeat of the Xiongnu. Liu adds a round Han dynasty roof tile end, an 18th- and 19th-century collectible admired for the ancient, innovative calligraphy decorating end pieces. It contains, appropriately, eight ideograms promising longevity.

Also reproduced are three examples of vernacular calligraphy; a personal letter, an envelope and a printed textbook. The textbook is significant. It is in the Manchu language – to inject a contemporary political reference – since Liu created his work in 1911, the year Manchu rule was overthrown. Finally, he impresses a seal reading ‘Ten thousand years of longevity without end’ in the complex seal script, no less, to serve as his signature.

Bapo Was Mainly Created on Paper

Most bapo were executed on paper and sometimes on silk, but an exceptional specimen featured silk embroidery. Translating painting into embroidery or tapestry was a costly and labour-intensive undertaking, and bapo’s relatively low status suggests they were rare.

Meeting Immortal Friends (undated) by an unidentified artist depicts a rubbing of a famous ancient stone inscription first discovered in 1005 carved on a cave wall. ‘A meeting with immortal friends on the 18th day of the 4th month of the first year of the Han An period (142)’ refers to an encounter between the writer and either celestial beings, or other members of his Daoist sect.

The embroidery is a faithful copy not only of the ideograms, but also of the stone rubbing’s ageing surface, ragged edges and cracks on the original stone. Its maker was true to the bapo ethos, exhibiting a skill matched by the work’s authenticity, complete with a red seal on the bottom right.

The First and Second Opium Wars

The advent of bapo coincided with mid-19th century China’s disastrous encounters with the West. They included the first and second Opium Wars and the sacking in 1860 of the Yuanmingyuan, ‘Old Summer Palace’ by British and French forces which resulted in the destruction of libraries and other art collections.

Also unleashed was a protracted period of domestic ferment beginning with the Taiping Rebellion that spilled over into the 20th century: The collapse of the Manchu order, the Republican revolution, warlordism and civil war were followed by the Japanese invasion and World War II.

Throughout this time, the genre emerged a natural platform for expressions of outrage. Couched in hidden poetic and political references, they challenged viewers to decipher their real meanings as they addressed a litany of pressing concerns.

One of the most poignant, Burned, Ruined, Damaged Fragments (1938), a series of four paintings by Li Chengren (dates unknown), informs the present by referring to lessons from the ancient past. He compares the Nanjing Massacre of 1937 during the Sino-Japanese War when up to 300,000 people were said to have perished, to an ancient calamity that occurred in 213 BC.

That year, the First Emperor of China, Qin Shi Huangdi (r 221-210 BC), who unified the country, and standardised the Chinese writing system, destroyed much of its achievements by burning books critical of his rule. Li interpreted the horrors of 1937 as equal to this historic conflagration that has left an indelible mark on Chinese civilisation.

Unconventional Bapo Paintings

Some unconventional bapo paintings reflected the wisdom of ancient aphorisms. The artist, Chen Bingchang (1896-1971) who was born with only a thumb and one finger on his right hand, gave himself two sobriquets: Erzhi, meaning ‘two fingers’ and Yingwu, ‘should have been five’.

Coming from a cultivated family, he was determined nevertheless to seriously pursue writing and painting, and trained his left hand to do so. Willing to Reside in a Shabby Alley (1945) alludes in passing – but without self-pity – to Chen’s own physical shortcomings.

His fully open folding fan contains a four character composition, ‘bao can shou que’ on an imprinted seal, which might be translated as ‘protect the deficient and look after that which is lacking’. This expression to cherish broken, worn-out things and damaged remnants may date back 2,000 years, yet adequately conveyed some bapo sentiments.

Social and Demographic Change

Social and demographic changes in the interim had brought accelerated urban growth to early 20th-century China. The developing commercial culture of Shanghai, its largest and most sophisticated city, had a substantial impact on the pattern of artistic production. From the 1930s, the effects of newly installed mass media and the cinema also began making their presence known.

Yang Weiquan (1885-after 1940), a Fujian native settled in Shanghai, was a professional bapo artist active around the 1930s. He posted advertisements in the newspapers and made a living by selling his works. One, Untitled (1942) features -among antique remnants – what appears to be a rubbing of four ancient characters on a black background and green border.

It is actually a packaging for a British toothpaste popular in 1930s Shanghai, and was intended as a visual joke. There is also a fan inscription reading: ‘The books and pictures are all broken and eaten by worms, what is there to be sad about? The Han tile, the Qin brick, old and ancient. Today the bronze vessels are scattered. We people feel the swift changes of the world’.

‘Yang’s work was more decorative and though still depicting works of epigraphy and painting, lacked their deep scholarly references,’ says Dr Berliner. ‘He also hired a daibi, ‘substitute painter’, Zheng Zuochen (1891-1956), who painted most of the works we see today with Yang’s signature.’ Sceptre (1950) by Zheng, which is on show, is a collage shaped like an ancient Chinese imperial staff called ruyi, a homonym that translates literally as ‘may you achieve all that you desire’.

This type of painting, custom-made to fulfil social roles and obligations in Chinese society, was probably designed for clients. It brought good tidings, its punning homonyms echoing symbolic messages of congratulationary ‘new year’, ‘birthday’ or ‘farewell’ pictures, popular since the mid Ming.

The exhibition, an unprecedented inquiry into bapo, has cast fresh new light on the subject and given it a well-deserved place as a modern Chinese artistic creation in its own right. As Nancy Berliner says: ‘It is a rare opportunity – and incredibly exciting – to discover, investigate and put back into the public knowledge a historic and radically modern-looking art form that had never been recorded, and that was all but forgotten.’

BY YVONNE TAN

Until 29 October, China’s 8 Brokens: Puzzles of the Treasured Past is at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Avenue of the Arts, 465 Huntington Avenue, Boston, www.mfa.org