SELDOM DOES AN artist meld social consciousness and graphic sensibility with the adroitness of Taiwan’s Chen Chieh-jen. While Chen’s work deals with such issues as the economic and social dislocations of modern life and man’s inhumanity to man, it does so without being either condescending or preachy and the emphasis is on the dignity of the individual, no matter what his or her walk in life may be. Although Chen’s artistic sensibility has been nurtured by his native Taiwan and his work has been filmed there, what makes it so accessible is the universality of its themes.

Chen is a self-trained artist. After graduating from a technical institute in Taipei in 1978, he participated in underground performances and installation work at a time when Taiwan was still under martial law. Although martial law was lifted in 1987, it was not until 1996, the year of the first presidential election in his homeland, that Chen began to devote himself to art. His first works were photography, and in 2002 he turned to video, the medium in which he now works.

Chen Chieh-jen’s First Video

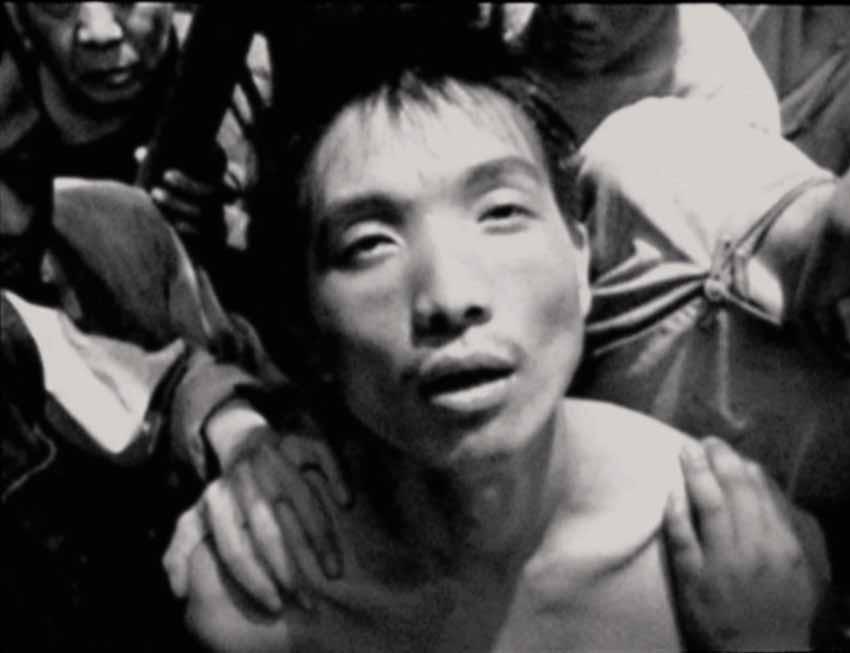

Lingchi: Echoes of a Historical Photograph, his first video, was shown at the 2002 Taipei Biennial and has since been exhibited at various venues in Asia, Europe, and North America. Inspired by a series of photographs of a lingchi execution (loosely translated as ‘death by a thousand cuts’), a form of punishment practiced in China until 1905, when it was banned—the 21-minute video is not easy to watch. By juxtaposing a reenactment of a lingchi execution with photographs of historical and more recent sites of destruction, which are framed by the circular wounds on the condemned man’s chest, Chen forces viewers to consider what is barbaric about their own time and culture.

The photographs on which the video is based were taken by a French soldier in 1904 or 1905 and were widely circulated in the West, where they were regarded as evidence of the barbarism of the Chinese. But the scenes of destruction included in Chen’s video – the Old Summer Palace in Beijing, burned to the ground by British forces in 1860; the laboratories in Manchuria where the Japanese conducted research on chemical and biological warfare in the 1930s and 1940s; a political prison from the days of martial law in Taiwan; an abandoned RCA factory outside Taipei that was the site of environmental degradation – point to the barbarism of human beings of all cultures and eras.

By focusing on the faces of those in the crowd who silently watch the execution, Chen Chieh-jen reminds us of our own passivity in the face of barbarism, or of social injustice. As Western viewers watch Lingchi, which is project onto three screens, they may call to mind triptychs depicting the crucifixion. The expression on the face of the condemned man, like that of many Christian saints portrayed in Western art, hovers between pain and ecstasy.

The Original Photographs

Chen explained, when I spoke with him in New York, that when the original photographs were circulated in the early 20th century, Westerners related them to Christianity, but that was not his intent. Although he is aware of the use of the triptych in Christian art, the reason he chose to use three screens for this work was to emphasize the fragmentation of the body of the man being executed and the fragmentation of his vision, since he is shown being drugged with opium before the execution begins, and the vision of the viewers.

As for the expression on his face, Chen Chieh-jen explains in a booklet of Artist’s Statements that accompanied an exhibition of his work at the Asia Society in New York in 2007, ‘For me, this inscrutable smile . . . is both passive and active. It is also the smile of a person who cannot flee, as he crosses from the present moment of cruel torment to face the future. This incomprehensible smile also demands a response from those of us who view it’.

Factory (2003)

After creating Lingchi, Chen Chieh-jen turned his attention to others ‘who cannot flee’, to workers who have been laid off from their factory jobs, with little hope of finding other employment, by companies that have no regard for their welfare, and to the abandoned buildings that were once the sites of their livelihood. In Factory (2003), Chen asked a number of women who had been laid off from a a garment factory in the 1990s to return to the site of their former employment and be filmed in the factory, which had been abandoned for seven years.

There is a poignancy to the parallels between the life cycles of the women who enjoyed gainful employment in the factory in their youth but are now no longer needed and the cyclical nature of the global economy, which creates economic booms in countries where labour is cheap but then moves on to other areas of the world, searching out new sources of even cheaper labor. Bade Area (2005) and On Going (2006) deal with similar issues and, particularly the latter, with the helplessness of the individual in confronting them.

Unlike Lingchi, which is shot in black-and-white, Factory, Bade Area, and On Going are filmed in colour, although the colours are, for the most part, so muted that they seem almost gray, and even the workers’ clothing and the pallor of their skin take on the tones of the dust-covered chairs, desks, and machinery strewn about in the derelict factories.

Chen Chieh-jen’s Three Videos

While all three videos are compelling, they are more closely related to film than to still photography and do not have as strong a visual impact as Lingchi or Chen’s recent video, The Route (2006), which was commissioned for the 2006 Liverpool Biennial. The Route was inspired by the Liverpool dockworkers strike of 1995–98. In 1997, dockworkers around the world, in sympathy with their peers in Liverpool, refused to unload cargo from the Neptune Jade, a ship that had been loaded by scab.

The Neptune Jade was finally unloaded in the port of Kaohsiung, Taiwan, where dockworkers were unaware of the international strike. For The Route, Chen staged a belated sympathy strike by Kaohsiung dockworkers. Shot almost entirely in black-and-white, the closeups of the workers’ faces, sweat dripping down their brows, and the strong diagonal of the picket line become etched in the viewers’ mind, much the way the images in Lingchi do. As in the rest of Chen Chieh-jen’s videos, there is no sound. The images speak for themselves.

Another of Chen Chieh-jen’s current projects is a departure from his work to date, Chen as he travels along the border of China, from Vietnam to the northeast. This work has been commissioned by the Reina Sofía National Museum Art Centre in Madrid, where it is planned to open this year. It will then be on view in Beijing in 2008.

BY CAROLINE HERRICK